By Farah Barqawi

I was having a lazy Saturday morning in my kitchen when Mama called on video. It was still ten a.m. in Brooklyn, but it was five p.m. in Gaza. I fixed my messy hair and picked up the call only to realize she was not calling from her home.

The only thing I saw next to my mother’s face was the fabric of the back of the couch she sat on, but I immediately recognized the room she was in. She was at my cousin’s, Wafaa, the eldest daughter of my Aunt Youssra.

It was the first room to the left after the corridor from the entrance, with a wide and partitioned wooden door that would usually be open if the visitors were close relatives. The door would be closed, however, when strangers or distant relatives or male-only visitors would come, as it overlooks the rest of the apartment to the right. An average Gazan guest room, with a set of puffy couches and chairs, curtains covering the only window on the middle wall, a couple of two-framed Quranic verses fixed on the windowless walls, and a set of wooden stands on each corner carrying small ornaments, vases, and special wedding or newborn souvenirs gifted by close family members.

I was in that room, and in Wafaa’s home, only once. Seven months earlier, in April 2021, I had visited Gaza after nine years of partially chosen, partially forced distance. Nine years of attempting to craft an independent life, and over busying myself with work, feminism, art, and travels to new and familiar places. And nine years of repetitive and extensive closures of Rafah crossing, and the precarious road conditions and Egyptian military checkpoints that were planted all the way from Cairo to Gaza, the only road to where my mother and her family live.

The nine years could have been longer if it weren’t for the Covid-19 pandemic, the sudden slowness of the world and the inflated uncertainty about what we can lose and when. The decision to finally visit Gaza in April 2021 came more easily than I expected, despite the risk. I had made it my intention to visit before I embarked on my then upcoming journey to the U.S. to pursue a very precious MFA opportunity, which came with a scholarship and a chance to start life all anew in New York City.

I wanted to visit Gaza and see and do all that I hadn’t been able to see and do in the earlier nine years. To meet new family members (lots of them, as my cousins kept having kids whom I only got to meet through phone screens). So, I went for two weeks in April, not enough time to recapture everything I knew or to absorb everything I didn’t yet know. But it was enough time to interrupt the pattern of Ghorba before I fell into it again; before I made it to New York and became busy again and scared of getting locked in by the closure of borders again, living in a state of longing again.

Which is where I am now, literally.

My attempt at recollecting my one-time memory of the room at Wafaa’s home was shortly interrupted by a quick movement of the phone. In a second, Khalti Youssra filled the center of the camera frame, wearing one of her home gallabiyahs with a layer or two showing from underneath, her thinning or almost disappearing graying hair tied into an unseen tiny cookie knot in the back. Moving her neck, eyes, and jaws filled with decaying teeth, she asked me how I was doing.

Ahlan Khalti. I’m good, how are you doing? I answered very quickly.

Exhaling with what seemed like acceptance or surrender, she answered automatically that it’s going okay, stating that I gave her Wahsha. I miss you more, wallah! I said but my hoarse voice drove her to ask me if I was sick. No, I am still waking myself up and finishing up cleaning from last night’s gathering. I made Maqloobeh for a lot of people.

It was Thanksgiving time in New York, and despite having no reason to celebrate it, the long weekend seduced me into this foreign tradition, so I had friends over on Friday night, avoiding the usual Thursday night, and I cooked Maqloobeh. Then, of course I stayed up late and this always affects my throat. But I am drinking a hot cup of Miramiyyeh. This should fix it, I explained.

Miramiyyeh only? In the morning? She was puzzled, as usual, with my distantly developed habits.

Yes, I like it this way. I sometimes drink it before coffee. (It’s quicker too, I just pour hot water over dried sage leaves). I paused for a second before adding in one long clumsy breath, that I still needed to finish cleaning up from last night, the dishes are all washed, it’s just the pots that need deeper cleaning, so I soaked them overnight in soap.

Squeezing her eyes with a half-smile, Khalti Youssra tried to decipher what I was aiming

at by my unnecessary defense. She assured me that it was all normal. Don’t worry, we are not new to your cleanliness, and we cannot see anything anyway.

I tilted the phone towards the stove to show her the pots sitting there from last night. I had no clue why I was continuing to prove that I had a solid cleaning strategy for the aftermath of two huge pots of Maqloobeh, while my aunt continued to stare at me with her squeezed soft eyes.

*

Since my last departure from Gaza, I cannot hold eye contact while talking to Khalti Youssra or make sense of the way she looks at me when the phone is pushed to her by Mama during a video call. The conversation with her wouldn’t last for more than a few minutes, enough to confuse me and throw me into questioning what she sees when she sees me, and how can she handle seeing me at all?

I cannot forget how she refused to talk to me on the phone for a week or more after what happened, I guess because it all happened right after I left. Because I came back to Gaza and left in a glimpse of an eye. And because Doaa left right after in a glimpse of an eye too. Because of the love Doaa and I had, the bond we had, despite the differences we had.

Before I left Gaza for college in Cairo back in 2002, for what now can be called for good, Mama and I used to live on the ground floor of the same small building where Khalti Youssra and Doaa, her youngest daughter, lived too (she moved out years later when she got married while I was already abroad). Living in the same building gave us all the time and space to be together, to grow together, despite the differences inherited from our mothers, as if these differences made us closer, or at least enlarged our hearts, and flexed our souls. Like Khalti Youssra and Mama, Doaa and I were three years apart, many worlds apart, a committed Muslim and a committed atheist, so different yet so intimate like “Tizien bi Libas,” two asses in one underwear.

I laugh at my inappropriate joke in the presence of our loss and the excruciating pain writing about it. But it is the truth, and it is what Mama or Khalti might say if they get a safe chance to, away from kids and strangers.

By the way, Wafaa cooked Maqloobeh today too! Mama noticed the short silence and filled it, as usual, with a comment.

*

I felt a sudden embarrassment, talking about cooking Maqloobeh as if it was a big achievement. I don’t remember the last time I tasted Wafaa’s food, but I know that over all the past years of marriage and bearing and raising five children, she became an expert in cooking huge amounts of different kinds of food at least three times per week if not on a daily basis, plus cooking even larger amounts for a larger number of mouths when she invites the rest of her family over for a food gathering. It was a mere coincidence that she cooked Maqloobeh that Saturday; she could have cooked any other complicated dish, and she wouldn’t make such a scene of it.

My arrival to Gaza in April 2021 coincided with the beginning of the fasting month of Ramadan, which usually comes with a race of Iftar gatherings. Three days into my arrival, Wafaa and her husband invited me and my mother along with her mother, Khalti Youssra, over for an Iftar dinner. Knowing my closeness to her youngest sister, Doaa, she also invited Doaa along with her husband Ezzat and her kids, Azeez, Zaid, and Adam. Wafaa didn’t cook that day though. She wanted to offer us something fancy in celebration of my visit, so they ordered a few kilos of mixed grills: Shish Kebabs, Shish Tawooqs, and Kefta fingers. She did fry what looked like hundreds of sticks though, peeled, and hand-cut from what perhaps made seven kilos or more of potatoes.

To our surprise that day, Doaa was the one who insisted on cooking us her signature dish. She called it Taj Mahal, which was some sort of adaptation of an Indian dish that has chicken, curry, and cream. Anything else Doaa cooked was mocked and made fun of. She wasn’t the most trustworthy at cooking up to the standards of my mother’s side of the family, nor did she swim in the right social pool of married women and mothers. Still, she was the “house of secrets” for Khalti Youssra as Mama always says. She was Khalti Youssra’s youngest but wisest daughter. She was the funniest mother. She was a supportive sister. But she was not made for cooking.

We arrived an hour before Iftar that day. If you won’t be helping, it doesn’t make any sense to arrive earlier in Ramadan since you cannot be offered any drinks or food before the Iftar time. But Mama, Khalti Youssra, and I arrived early because Doaa and her boys arrived even earlier. She probably spent the last few hours before Iftar cooking her Taj Mahal, and I wanted to spend as much time as possible around her and get to know her kids more closely.

Before this long-awaited visit to Gaza, I had only met Doaa’s older son, Azeez, when I last visited nine years earlier. He was only six months old then. But her other two boys, Zaid and Adam, I only knew them from the calls, and photos and videos sent to me over the years. Despite not knowing me so closely, the kids were the first to welcome me back home after nine years of not knowing me, by sneaking in with their mother, Doaa, who had the key to my mom’s apartment, leaving me three heart-shaped helium balloons. When they showed up the day of my arrival that spring, I took a video of them holding the balloons down before releasing them to hit the ceiling. It was such a surprise to see how baby Azeez became tall and wide, but it was even more comforting to see Zaid’s curiosity and Adam’s crazy laugh that I had only seen before through the lens of the phone.

That Iftar evening, Ezzat, Doaa’s husband, arrived last, as the Maghrib Adhan (at sunset time) was announced, and we were finally allowed to eat. Abu Azeez, as they all call him, was commissioned by Doaa to buy the sweets. Not any sweets, but the sweets I craved the most, Bulbul Nests; layers of flaky pastry, rich with ghee, stuffed with ground almonds or pistachios, and rolled into fingers. Arranged on a large tray, drenched in syrup, and crowned with pistachios.

He brought three kilos, to have enough for everyone at the gathering and to leave me some to take back home. He is tall and thin, like Doaa is tall and thin. He studied law but worked with his brothers in the family business, a workshop on the ground floor of their building where they fixed car motors. Calm like a cat, he sat next to me on the two-seater couch in the guest room at Wafaa’s that evening after Iftar. We talked about traveling and the last time each one in the room had traveled outside of Gaza. Most of the adults in the room had at least traveled at some point to Saudi Arabia to perform Umrah and Hajj rituals, except for Abu Azeez. He smiled at me and said, I’ve never left Gaza.

Not even once? Do you want to travel though? I asked.

Not even once, I’m forty-four years old now. Who knows, I might never travel, and it’s okay, I have lived this long without it.

Who knows; we all know now.

*

The cleaning can wait. Tell me now, how was the rice? Was each grain on its own like Khaltek? People have always commented on how I manage to keep each grain of rice as it is. Rozza over Rozza, she giggled at her Maqloobeh pride.

I answered with similar pride. It was a success, yes! But I don’t like to use Basmati rice like some people do. I prefer it with Egyptian rice, the thicker grain appeals more to me!

She nodded, between astonishment and understanding. You know why people prefer Basmati? Because it is easier to keep each grain on its own.

Really? So, it is not because it looks fancy and more suitable to impress the guests? I drew a slight smile as I teased her, then asked her, What about you? Which rice do you prefer?

*

I asked her about her rice choice because the other questions I have, perhaps, contain no choices. (Do you hear what I hear when I find myself in sudden silence before and after storms of noises and conversations? Do you feel the cracking of walls and ceilings and poles so deeply that it electrifies your arm hair and cracks your backbone? Do you see what I see right before I open my eyes after each sleep or an attempt of sleep or when I stop to receive a rare ray of sun light at a street corner during one of my daily walks? The image of the couch in the salon and the four bodies of Doaa and Ezzat and Zaid and Adam slowly getting squeezed, then crumbled, creating a spongy bubble for Azeez to hide in and make it till the morning comes, does that image keep blinking like an unanswered call behind your eyes?)

I didn’t ask her all of that. I wouldn’t have, and I couldn’t have let it out of my scratched throat. I kept reminding myself, we are talking about Maqloobeh.

*

If you haven’t eaten an original Palestinian Maqloobeh before, it is a pot filled with layers of rice, a meat type, a main vegetable, and some varying additions of potatoes, tomatoes, and sometimes chickpeas, depending on the taste of the person cooking or the preference of the eaters.

When asked What did you cook the Maqloobeh with? this would mean: what type of meat did you use? And what was the main vegetable? So, you need to make a choice between red meat and chicken, and to decide whether to use eggplants or cauliflowers or both. Each combination makes a totally different Maqloobeh. The rest is details.

For that I have a simple rule that I inherited from my mother: if it’s with eggplants then I use chicken, and when it’s with cauliflower then I use red meat, but not everyone likes cauliflower, so in the case of big gatherings, I usually go with the first option.

After it’s done, it is flipped upside down to be served. If it holds itself like a cake, you’ve earned a full mark.

*

Talking about food struck me suddenly with hunger. I fixed the phone on the kitchen table and opened the fridge, reaching out for some leftovers. By that time the phone had moved back towards my mom who was confused by the awkward angle of the camera. What are you doing?

Nothing. I decided to have Maqloobeh for breakfast. Raising my eyebrows in what seemed like asking for permission to be lazy and eat lunch food for breakfast, I looked at Mama and stuffed a full spoon of soft rice in my mouth then asked Is Azeez there as well?

Before swallowing or finishing my question, Mama had already shouted, Azeeeeez! Come quickly to talk to Farah. And in a second, Azeez was holding the phone.

Kefak habibi? I asked. Alhamdullelah, he answered.

Azeez’s ten-year old face didn’t differ much from his baby face. His skin is dark, his eyes are dark, and his teeth and jaws might one day need braces like his mother’s did when we were teenagers. His gaze was drowsy since the first time we spoke on video after what happened. I don’t know if this is his usual gaze into a phone camera because I was not used to calling him before. It’s Doaa who I called. Doaa who conveyed the messages and news and the funny curious questions by the children to me, then shouted out to them to bring them out of play time to say hello, to see my cat or to see the snow in wintertime.

How is school going? I tried to focus on practical questions. Questions that might have answers. It’s going well, I got full marks in all subjects, except for Math where I lost a few points. (Success! I got one answer.)

Wow! You’re such a clever boy! No answer. He gazed back with a silent, slight smile. When is your winter break? I tried again. I think it is at the end of December, he answered this time but with little interest.

Doaa’s birthday is at the end of December. I wondered if this mattered to a kid his age or if he is able to make the similar contextual connections an adult could make, or at least the connections of dates and numbers I could make. The counting I always do. (First birthday after what happened. She would have turned thirty-nine, one more year was left for forty. I couldn’t imagine her becoming forty anyway. My closest cousin. First uncelebrated birthday in a suspended lifetime.)

Azeez was staring, and I was not sure what to ask next. Azeez. The dear one. The rare one. It was not one of those contemporary names my friends gave their kids, nor a familiar one. It gave him what seemed like a bigger outfit, a larger personality. But now I know. Azeez. The rare one. The only one. Arabs traditionally say, Each one has a portion of their name in them. Azeez. The only one left.

*

With hesitation I pushed myself to ask Azeez about his feet and if it’s become easier for him to walk on his own. I assumed so, after six months of healing from severe first degree burns, skin replacement operations, and physiotherapy. I wished I had enough interesting questions about school and vacations, but I felt some responsibility to ask and to let him know that I didn’t forget. Yes, Alhamdollelah, much better, he said calmly, and I followed it with, Great Habibi. I’m happy for you.

And I was happy for him, I really was. But my heart was not content with the answer; for what I really wanted to ask him was how he could walk out to the street from his paternal grandparents’ house, where he spends the weekdays now, and how he goes back there having to pass by that piece of deserted flattened land. The one right in front of the grandparents’ house. The one which once held together a three-story building that shielded that old house from Wehda street. The one that was home to three brothers from the Al-Qulaq family, their wives, and kids. The one that Azeez was brought home to after he was born. The one where he lived all his life in up till mid-May 2021, in a small apartment on the first floor with his mother Doaa and his father Ezzat, joined over the years by his younger brothers, Zaid and Adam.

*

I visited that building during my visit to Gaza in April 2021. Doaa, too, wanted to invite me and my mother over Iftar, and due to the limited space of her small apartment she had only invited her mother, Khalti Youssra, to join us. The night before that Iftar evening Doaa declared that she was going to cook Mahashi: zucchinis, eggplants, bell peppers and potatoes stuffed with seasoned rice and minced meat and cooked in tomato sauce. I was again shocked by her courageous move to offer to cook such a complicated dish. She stayed up that night digging pits out of the veggies to be stuffed. She also made a vegan version for my mother. The next day, while we were all sitting and ready to eat, after the Maghrib Adhan was announced, she announced that she had called my mother earlier in the day asking for urgent directions because she didn’t want to mess up the food, which clearly, she was not the best at handling. And my mom took it from there to tell us, and wink to Khalti Youssra, jokingly, I swear, of course I knew she’d call me, your daughter Doaa is Habbouleh (goofy) and has nothing to do with cooking.

When I arrived to Doaa’s apartment on the first floor that day, I brought with me a huge plastic Kinder Surprise Egg that carried five pieces of each type of Kinder chocolate, including five eggs of course, because you cannot buy chocolate for the kids and forget Doaa. The big kid. And Ezzat, so that he doesn’t get left out of the chocolate craze. The kids ate their food so quickly that day because that huge egg was awaiting in their guest room.

It was the last day I saw the kids, because I had to leave Gaza so abruptly a few days later due to the unexpected border situation. I met Doaa one more time. We went for a long walk in Gaza one of the mornings when the kids were at school, and she called in sick for her work. But the last time I saw the kids was that Iftar evening, an evening full of Mahashi, laughter, and chocolates.

*

Three weeks after my visit to Doaa’s place, after that evening full of Mahashi, laughter, and chocolate, and two weeks after my abrupt departure from Gaza, that same apartment on the first floor stood no chance of surviving the Israeli missile attack on Wehda street that happened at 1 a.m. on Sunday, May 16th, during the May 2021 war on Gaza or what the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) called Operation Guardian of the Walls. The missiles that dove deep in the belly of the street into the foundations of the building and caused the cracking of the walls. The cracking that caused the crumbling of bodies. The cracking and crumbling that don’t leave my ears and eyes till now.

How could Azeez walk in and out of there? And if he could, has it become easier?

They are not fully healed yet though, they still need some time, my mother summed up the situation of Azeez’s feet, shouting from out of the frame and moving the phone rapidly. Look!

I don’t know what she was thinking. The camera flipped in a second and the phone was getting closer to his feet, to the skin of the toes on the right foot then the left foot. I looked and thought that people have accidents of all sorts, and this one was, Alhamdullelah, one that didn’t leave him feet-less, only the skin around his toes was crumbled and stinging in an attempt to heal.

Yeah, yeah, I see, good, good, good, good. I was waiting for my mother to stop the show, until I heard Wafaa’s voice: Alhamdulellah, all is well, nothing left, khalas. That might have pinched my mom back into awareness, softly but surely, finally. Wafaa was next on the screen.

*

Doaa had taken a different route than her sister. She first finished her engineering degree and worked as an architect in Gaza. She only got married years later and then became a mother as well to Azeez, then Zaid, then Adam. When Doaa became a mother, the two sisters were kind of re-united on their pre-dictated journey of marriage and motherhood, two sisters and two mothers living within two separate families and re-uniting weekly at Khalti Youssra’s place, exchanging experiences and advice and rantings, performing the rituals of women’s domesticities.

During the last few years, Wafaa had been Adam’s nanny too. Azeez and Zaid went to elementary school, but Adam was still too young. On her way to work every day, Doaa used to drop Adam at Wafaa’s place to spend the day. Wafaa is a housewife, and she technically was his second mother. He indeed called her Mama, and since he was much younger than Wafaa’s children, he was the joyful spirit of the house, the spoiled one.

Out of all family members, Wafaa was the most difficult to speak to. We were not used to talking much before, and since Doaa left us, we both almost choked when we spoke to each other on the phone.

How are you Foufou? she asked me as I was stuffing another bite of Maqloobeh into my mouth. I’m good. How are you, habibti? I answered after I swallowed.

Alhamdolellah, she said, and it seemed to me she was looking for another mild question to ask me as much as I was inspecting her face and pale eyes to see if she looked better than our few short calls in the previous months. If there was less paralyzing sadness. If it became easier for her to talk now that it had been six months and eleven days since Doaa’s departure.

*

I write Doaa’s departure with some hope of making it smoother to be mentioned, to be written, and to be received. But in the word “departure” I find neither solace nor ease nor smoothness. Rather a sense of betrayal and a flattening of how she was taken away from us and everyone who loved her. But I also find it hard to write about Doaa’s death. “To die,” like “to leave” and “to depart,” seems like a willful action, but she didn’t will it for sure.

I think of the word “tragic” next to “death” or “killing” and find it distant and journalistic, and I think of the expression “devastating accident” and find it more of a betrayal. Palestinian news portals called it “Al-Qulaq family massacre,” but I cannot handle seeing this title nor this repetitive piece of news, listing the names of people who mattered, buried collectively, in a glimpse of an eye, under their own house.

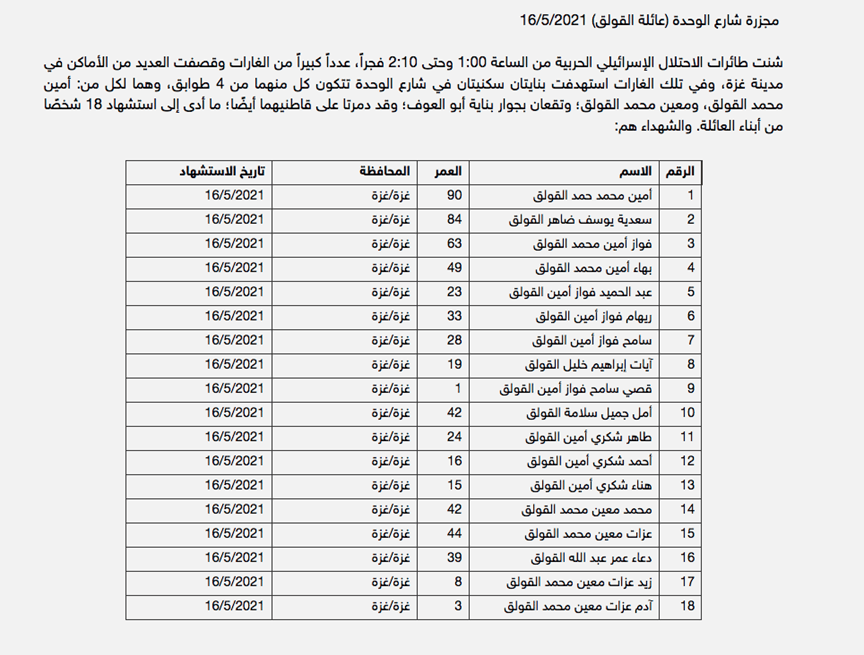

I don’t know how to find one word that captures the death she died on the sixteenth of May 2021. While searching for her death online, I found a table published by WAFA, Palestine News and Info Agency[1]. The news page is entitled “The most prominent massacres carried out by the Israeli occupation in the aggression against Gaza in May 2021.” And the Al-Qulaq family massacre comes third and last on that page as “Al-Wahda Street massacre (Al-Qulaq) 5/16/2021.” Doaa’s name appears number 16 on the table, Ezzat before her (number 15), and Zaid and Adam are after her (numbers 17 and 18). The website lists her last name as Al-Qulaq too; they assumed she went by it since everyone else on the list carried that last name. But Doaa had never used that last name. Perhaps it was forced into her ID since her marriage, perhaps the hospital documented the names using those IDs. This is not the point. She was herself, number 16 on the list, Ezzat before her, and Zaid then Adam after her. Azeez, miraculously missing.

I don’t know if any word can express the loss I cannot and maybe will never be able to articulate, in any language I speak. If any word will be fitting for all times and phases of grief and remembrance.

*

I kept studying Wafaa eyes and lips, waiting for a rescue from tripping on my own language or the lack of it. The silence did not seem to have eased for either of us. At least not until my Mama shouted again, from behind the screen as Wafaa’s face was still hanging on: But you haven’t told us! What did you cook the Maqloobeh with?

[1](2021, May). The most prominent massacres carried out by the Israeli occupation in the aggression against Gaza in May 2021.WAFA Palestine News and Info Agency. Page last retrieved on July 15, 2024, 10:30 am.

https://info.wafa.ps/ar_page.aspx?id=CbKqzha27953937363aCbKqzh.

Farah Barqawi is a Palestinian writer, educator, performer, and feminist organizer. She works across multiple genres and mediums, including writing, podcasts, singing, and theatrical performances. Her poetry and prose have been published in multiple languages, both online and in print. She co-founded two prominent feminist initiatives in the Arabic-speaking world: Wiki Gender and The Uprising of Women in the Arab World. In 2018, she wrote and performed her solo piece, Baba, Come to Me, which she toured for two years. In 2019, she produced and hosted a season of the Arabic podcast Eib (Shame), exploring themes of love, relationships, gender, and societal taboos. Farah holds a master’s degree in public policy from the University of Chicago (2011) and an MFA in creative nonfiction writing from New York University (2024), where she also taught creative writing to undergraduates. She currently lives in Brooklyn, where she remains deeply engaged in her communities and continues to advocate for the causes she is passionate about.