By Kathleen Rooney

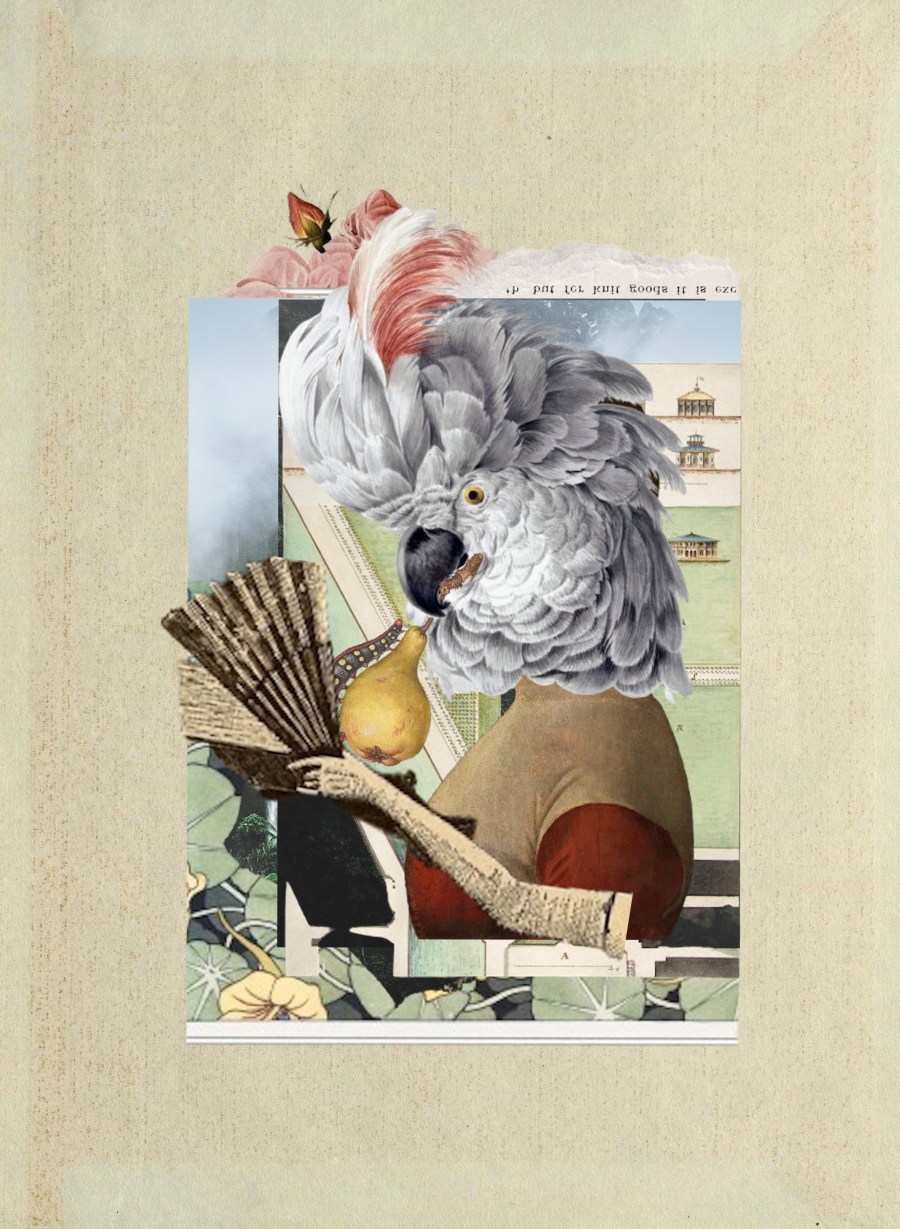

Featured Art: “Spring Returns and So Do I” by Leo Arkus

Usages tilt and words can wither, but they don’t get torn down like buildings do.

O archaic present tense second-person singular of will, of what wilt thy obsolescence consist?

To lose turgor from lack of water. To become limp or to languish. O language, if thou wilt not do as I insist, I shall shrivel and droop out of dry brown anguish.

Words whose referents no longer exist—place them in a room painted pale museum green, cool and clean, a calming space, filled with monstera, dieffenbachia, and schefflera, their leaves a-flap like floppy disks.

Modern humans suffer from what botanists call plant blindness, moving through life insensate to vegetation, failing to recognize plants at all other than something we might eat.

“Salad bar” originates in 1940 in American English, “fern bar” in the late 1960s. Do lettuce leaves look more appealing behind sneezeguards? Do ferns thrive in light cast by ersatz Tiffany lamps?

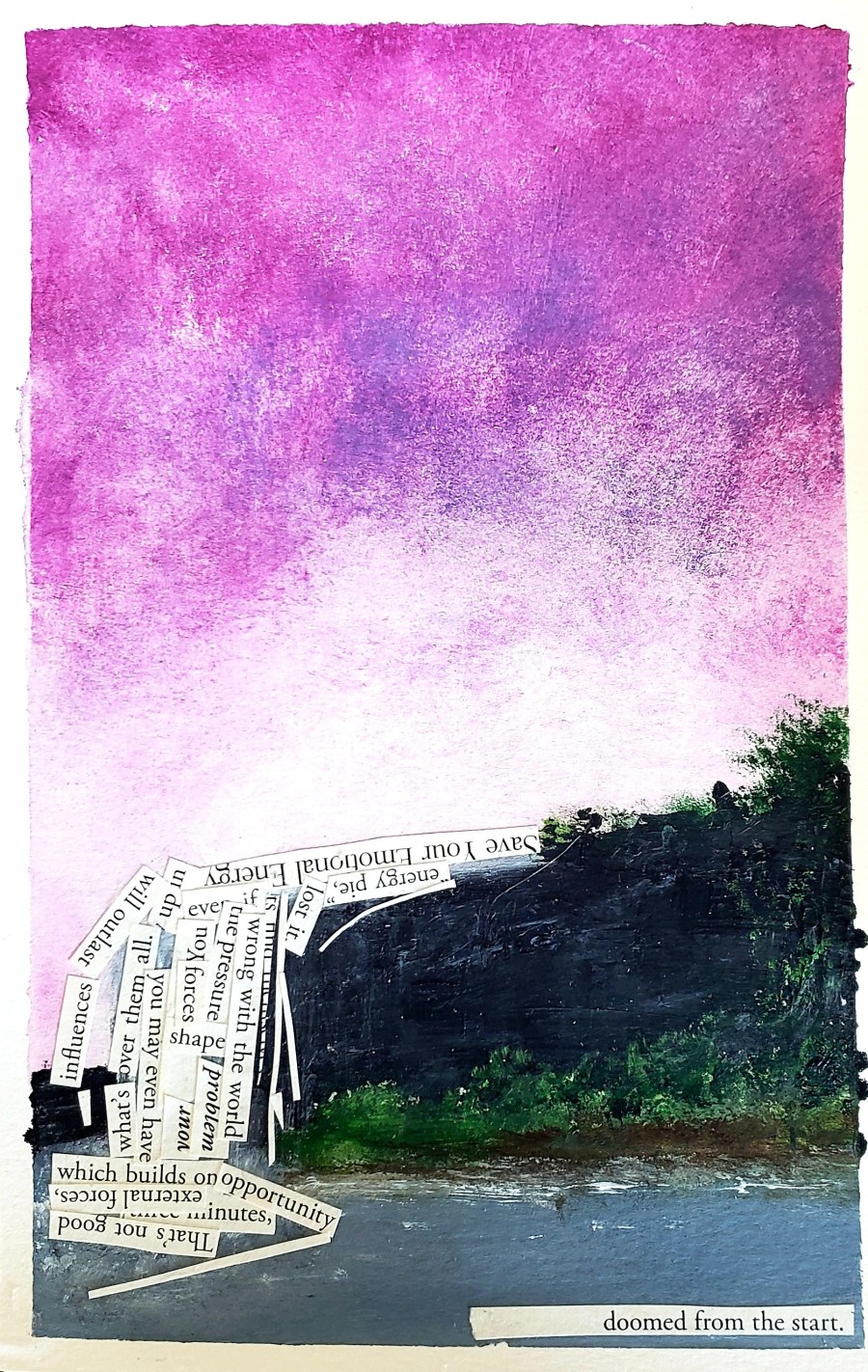

The flowers upturn their ferocious faces. Would that I could catch what I need from the sky.

Wilt Chamberlain’s full first name was “Wilton,” but his high school classmates called him “Wilt the Stilt.” Seven-foot-one is tall, but that’s nothing to a tree. He claimed to have had sex with over 20,000 women (despite being “shy”). You’d never catch a tree trying to brag about that.

At my elementary school, we put on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, abridged considerably. I laughed backstage at my friend Bryn, playing Bottom, declaiming at Titania: “Out of this wood do not desire to go. / Thou shalt remain here whether thou wilt or no.”

WILT as acronym—What I’m Listening To: Mort Garson’s 1976 album Mother Earth’s Plantasia: “warm earth music for plants . . . and the people who love them.” Soothing, tuneful Moog instrumentals.

Unlike certain humans I could name, no plant has ever said anything to spoil my mood.

What’s happening down there beneath the soil? Calibrate your sense of time to plant growth.

The dreams of plants unfurl with the slow force of a thousand forests.

In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky writes, “The centripetal force on our planet is still fearfully strong, Alyosha. I have a longing for life, and I go on living in spite of logic. Though I may not believe in the order of the universe, yet I love the sticky little leaves as they open in spring.”