Horn

by Robert Pinsky

Originally published in New Ohio Review Issue #7

This is the golden trophy. The true addiction.

Steel springs, pearl facings, fibers and leathers, all

Mounted on the body tarnished from neck to bell.

The master, a Legend, a “righteous addict,” pauses

While walking past a bar, to listen, says: Listen—

Listen what that cat in there is doing. Some figure,

Some hook, breathy honk, sharp nine or weird

Rhythm this one hack journeyman hornman had going.

Listen, says the Dante of bop, to what he’s working.

Breath tempered in its chamber by hide pads

As desires and demands swarm through the deft axe

In the fixed attention of that one practitioner:

Professional calluses and habits of his righteous

Teacher, his optician. The crazed matriarch, hexed

Architect of his making. Polished and punished by use,

The horn: flawed and severe, it nestles in plush,

The hard case contoured to cradle the engraved

Hook-shape of Normandy brass, keys from seashells

In the Mekong, reed from Belize. Listen. Labor:

Do all the altered scales in the woodshed. Persist,

You practiced addict, devotee, slave of Dante

Like Dante himself a slave, whose name they say

Is short for Durante, meaning Persistent—listen,

Bondsman of the tool—you honker, toker, toiler.

I Want to Talk About You

by Angie Estes

Originally published in New Ohio Review Issue #7

when starlings swell over Otmoor, east of Oxford, as the afternoon

light starts to fade. Fifty flocks of fifteen to twenty starlings, riffraff

who have spent the day foraging in fields and gardens suddenly rise

like a blanket tossed into the sky, a revelling that molts sorrows to roost

rows, roost rows to sorrows as they soar through aerial corridors and swerve

into the shape of a cowl that lengthens to a woolen scarf wrapping

and wrapping, nothing at the center but throat: thousands of single black notes

surge into a memory called melody, the lovers damned but driven on

by violent winds in the cold season when starlings’ wings bear them

along in broad and crowded ranks, extended cadenzas to pieces that

never get played, brochure for the flared tip that begins with the tongue

and lips of the embouchure wrapping the saxophone’s slurred

howl, scrawled signature of the sky. Thousands fly but never collide

in their pre-roost ritual, Dante’s long list of God’s works excited

raked left and right over leafless branches of trees until they

drop like the bodies of suicides, draped on thorns of the wild

thickets their cast-off souls become, unable to rise the way a wave

nearing shore will crest, something on the tip of its tongue

thrown back before it breaks and splays, starlings laid down

like the wave’s rain of sand or words falling

out of a sentence: art slings, we called them, grass lint, snarl gist, gnarls

sit. Art slings them this way, last grins, art slings swell, rove

over, red rover, red rover, send artlings right over, artlings

rove, moor to swell, write Otmoor all over

after John Coltrane

Misterioso

by Sydney Lea

Originally published in New Ohio Review Issue #8

John Ore stood up his bass and Frankie Dunlop laid his sticks on the snare.

They walked offstage but Monk stayed on hunch-shouldered and with one finger

hit a note and stared at his keyboard a long long time, then another

and stared and another and stared, not rising to whirl as he often would do

when he played this club or any other. He didn’t smile as usual,

benign, whenever he danced like that. He wore his African beanie—

I mean no disrespect, Lord knows, just don’t know what you’d call it—

his face beneath it both blank and rapt. I was rapt myself as I’d been

for the whole first set and in fact for years even then, but for other reasons.

I believed he was speaking to me somehow, that he knew my inmost sorrows,

my expectations. Of course I guess a lot of people thought so.

I was looking for eloquent mystery in those odd plinkings, which may

have been there,

though if so, it wasn’t for me to fathom. With the noise of chatter and movement,

I couldn’t have heard my heart lubdub but did. The last set ended,

he sat the same way after, playing lone notes as if contemplating

just where each came from. Right there in front of you! I thought. Who knew

that in front of him too lay those interludes of speechlessness,

his piano hushed, till he died like anyone else? I don’t want to riff

on what I dreamed Monk meant to my life, so small and young, comprising

only things that any man that age is bound to go through.

I don’t want a poem all full of lyric triteness, smoke-softened light

that glanced off bottles behind the bar, the sorrowful looks of his sidemen

as they left him—which may have been only quizzical. It was 1963.

I won’t go into history today, or politics,

or whatever else might make something grander than they truly are of my

thoughts.

There was only Monk. There was sound then quiet.

______

Sydney Lea’s thirteenth collection, Here, will be published in September (Four Way Books)

Piano Lesson

by Gregory Djanikian

Originally published in New Ohio Review Issue #7

My teacher is looking at me sadly

as if with the large droopy eyes

of a basset hound.

I’m stumbling through “Naima”

transcribed for piano,

my fingers tripping badly over

the minor 3rds, the flat nines.

On his face, such longing,

as if it’s the end of jazz,

we’re saying farewell.

I’m ready to start from the top

playing all the changes, the repeats,

and he’s holding his head in his hands,

swiveling slowly in his chair.

The song is full of smoke and aching,

like a woman in a shiny dress

walking through a dark hallway

haunting the man she’s loved.

I can already feel the nostalgia in it

for what has never happened.

There are so many gray clouds here

I should play “Blue Skies,”

or “Mountain Greenery,” their upswings

rising like colorful balloons.

Now I see my teacher lying on his couch,

cupping his forehead in his palm.

It must be raining in his heart

for a love of something so perfect

there’s no place to find it

not in this room anyway

where I’m bent over the keys,

the rapturous jazz

just out of my reach

and my teacher is closing his eyes

and I’m closing mine

and we both might be imagining

Coltrane behind us breathing into his tenor

a song of love and departure

so fluent it feels like rain

falling into a lake

and maybe whatever is lovely

and improbable is always floating away

down a rivulet of dreams

where my body is falling

and my hands are reaching out,

and I am almost touching

something like water, like silk.

______

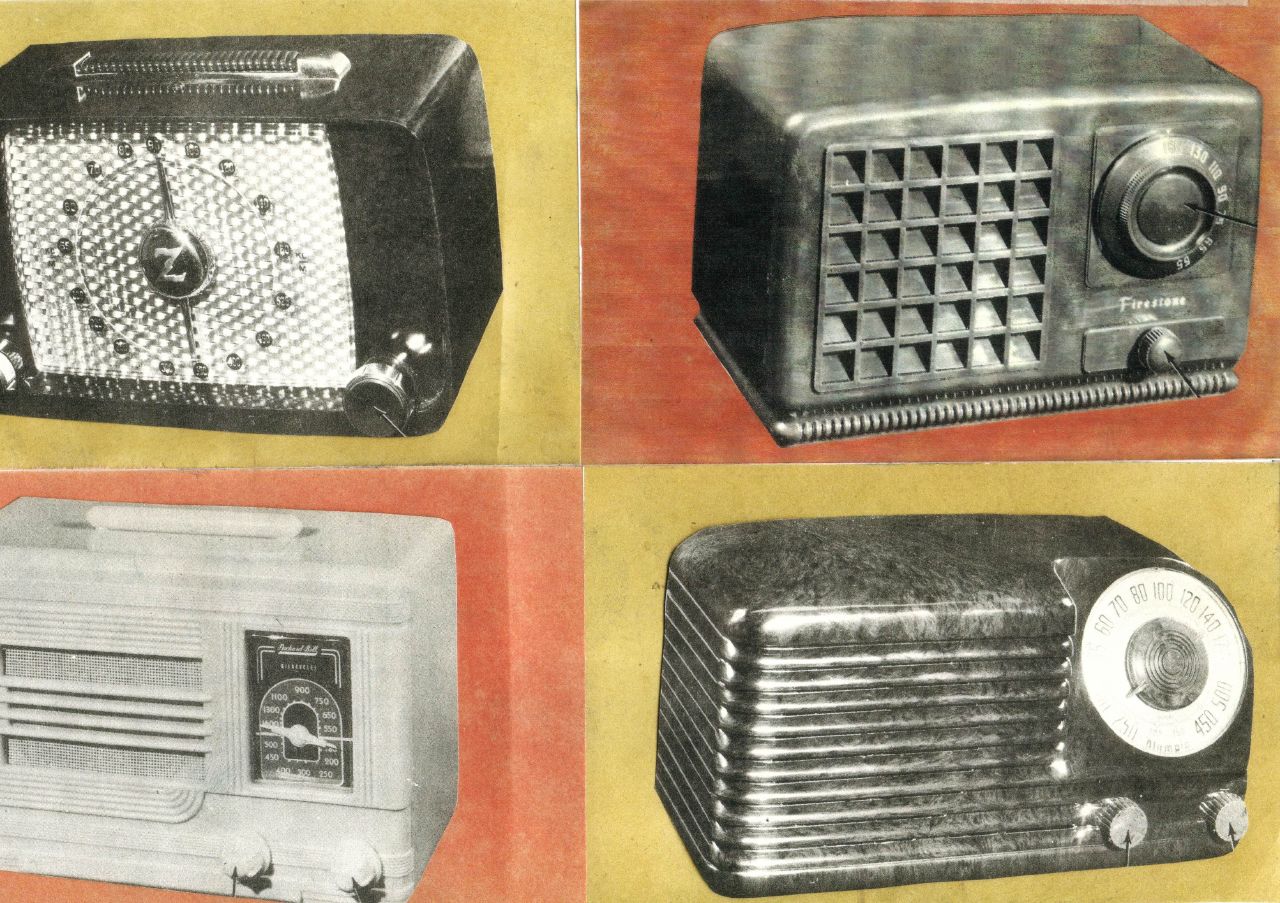

Artwork: “Dead Man’s Shoes” and “Radio chess grid,” by Jeff Kallet