By Michael Lavers

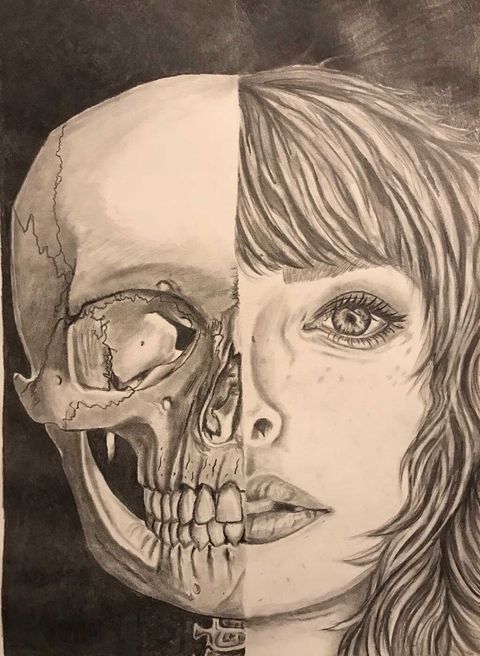

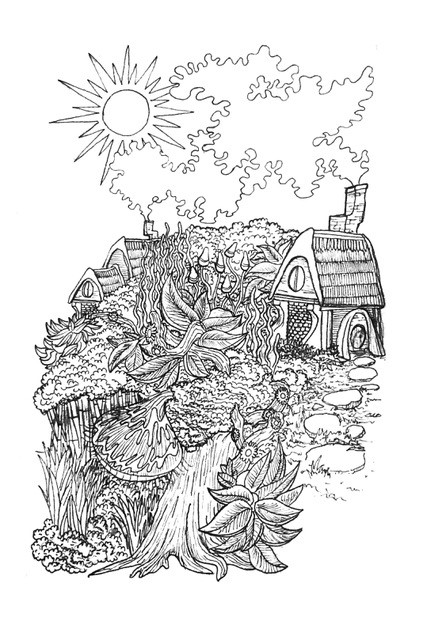

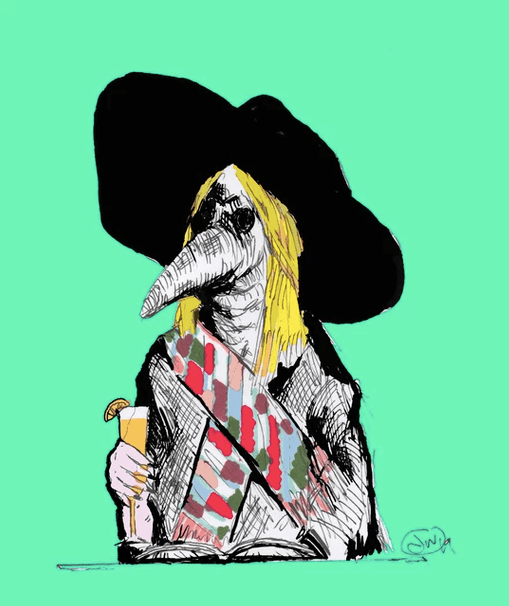

Featured Art: smokey lady by Byron Armacost

He made a poem and began it thus:

‘Muse, tell me nothing! Keep quiet, Muse!‘

—Jules Renard

Muse, tell me nothing! Keep quiet, Muse!

Not that you visit much, or would entrust me

with the grand advancements of the true and beautiful.

But just in case you have some scrap for me,

some local insight or a meager rhyme,

in case you wanted to drop by and put

the coffee on, and light a cigarette, and set your

sandaled feet up on my desk, and give detached

dictation, don’t. Don’t even think about it.

It’s no use telling me the purple buntings

are back, or how the horses down the road

steam after rain, or that two men are felling

pines over on Locust Lane, their careful cuts

inspiring some ode about the marriage

of form and function, muscle and grace.

Pester the poet laureate instead, or if

she’s scribbling already, visit Frank, my neighbor,

whose proclivity to mow the lawn late after dark

reveals a visionary’s knack for following

one’s own strange rules, no matter the judgment

of others. Pick anyone but me. Corner a dog,

or crawl into a cave, whisper to scorpions.

Or better still, stay quiet. Hey, don’t roll

your eyes like that. Don’t argue beauty

has its own use outside usefulness.

No, if you must speak, make it practical,

teach me to caulk the bathroom tile,

or judge others on a curve. But if it’s poetry

you have in mind, I’ll pass. Don’t tell me

that I’m going to die, and who knows when,

and therefore must put down the way

the pink light floods the valley like a wave,

then disappears. Shut up about the fleeting

beauty of the world—I get it. All things fade.

Just tell me what I can control, teach me

a trade, like felling trees: how to make sure

they fall just how and when I say: no sudden

turn, no frills, no mysteries, no doubts.

Only a simple line. Only a hard clear sound.

Read More