By Natania Rosenfeld

I am a person of excess. When I open my mouth, I say too much, too loudly; I put in too much food, too quickly; I gulp my wine and burn my tongue on coffee. When I eat hard candy, I crunch it all down immediately. I say what I feel at the moment of feeling, and sometimes, because I am a teacher, I say more than what I feel so my meaning will penetrate. You must do this as a teacher and even so, feel sometimes that your mouth has opened and closed for an hour and nothing audible has emerged. So, I am loud; I exaggerate. I am one of those creatures of whom it is said, “She doesn’t know her own strength,” like a lion cub or a small orangutan. The last time I visited my in-laws, I broke their china teapot. I didn’t mean to break it; my big hands dropped it on the floor without volition. It was at a moment when no one was listening to me, and I grew agitated; my hands shook.

My husband is a man of careful, clean movements, an ectomorph with the great, sad eyes of a giraffe. My clumsiness surely pains him, and I am pained by the difference between us. He deserves a daintier sort, a woman named Fiona or Lily who flits through life. I believe I should go away for a while so he can find this Lily or Fiona. I should live with a big man, a loud man, a man who spills on himself and bumps into furniture. With a man like that, I’d be at home. His flesh would deflect my unintended barbs and his noise would drown out mine.

Today a friend told me of just such a man, a friend of hers she says is pining because no one wants him. He is enormous, she said, like a bear or a gorilla, but so deft with his hands that he sculpts tiny figures, figures you can hold in your hand and stroke with one fingertip. These tiny sculptures, my friend said, are world-famous, but the artist is terribly lonely. Year by year, he has become more enormous, and year by year, he has grown less able to part with his tiny figures. He surrounds himself with them, but he is beginning to have financial troubles because he won’t sell them, though buyers beat at his door.

I want to meet him, I told my friend. I was not thinking of his brittle heart, only of resting against that body, being cradled in those paws she described as so deft, though so huge. And of soothing him as I fail to soothe my angular, pensive husband, or all those friends and relatives to whom my every word is like a slap, or at least, the sting of an annoying insect. Lately, there has been a silence between me and my husband, a silence that booms through the house. I must get away and leave him be.

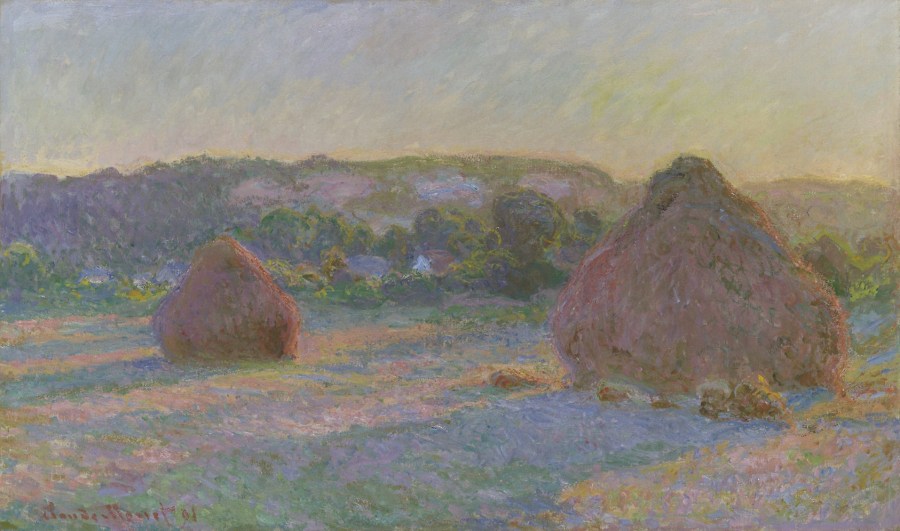

My friend took me to see the man where he lives in a white house by the gray sea. I had never seen so large a man: he towered over both of us, and when he embraced my friend, she was engulfed by his chest and belly. His hair and beard were shaggy and red, his sea-gray eyes were deep and glittering in their casements of craggy flesh. Enclosed in his ursine body, he seemed far away, unreachable. He served us tea at a table by a large window. The cups were porcelain and nearly transparent. How careful I was! And yet still I dropped my cup; it shattered, and splashed tea on my legs. Never mind, he said, it doesn’t matter. I got up to look for a towel, but he waved me back to the chair: Leave it. I watched him drink his own tea from a cup cradled in his paw like an egg.

After tea, we went to his studio.

“Here,” he said, “is my menagerie.”

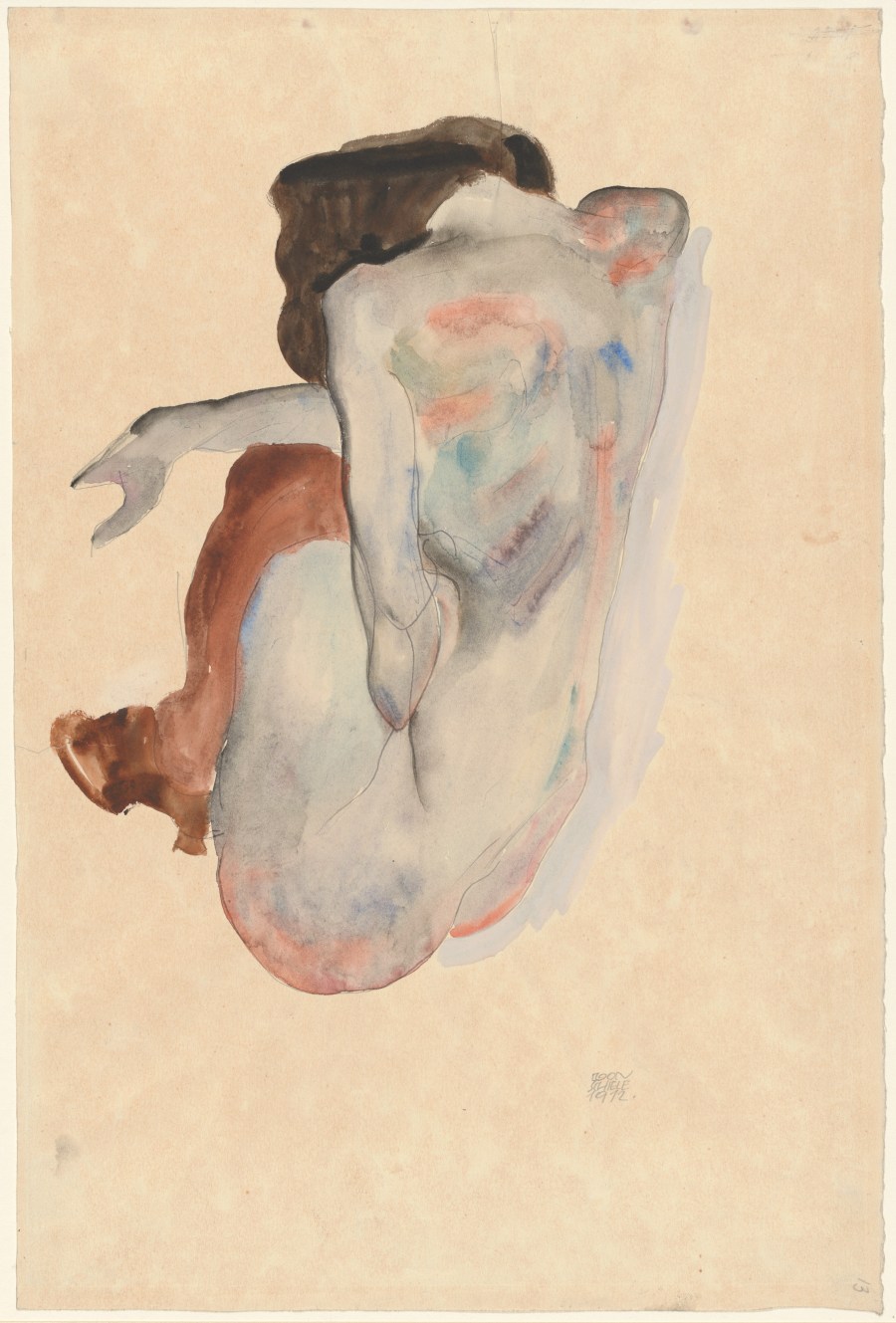

All over shelves, tables and windowsills were the tiny figures. I cannot describe them, partly because you had to touch them to fully understand. I was terrified when he picked up a sculpture not much larger than a thimble and handed it to me.

“But I already broke your cup!” I said.

He shook his head. “It doesn’t matter.”

For many minutes, he handed me the tiny figures. I held them, looked at them, became lost in the features of their half-animal, half-human faces, and handed them back to him. It was a kind of dance, like the movement of the midwife who takes the baby from its mother’s womb and hands it to the at- tending nurse.

“I have no children,” he said. “They are my real children.”

“I have no children, either,” I answered.

“Then you must find your real children,” he said. “And you mustn’t smother them.”

“Do you smother yours?” I asked.

“Maybe. I can’t give them up. When others come to take them away, I feel as though I’m sending them into exile.”

“But even real children leave eventually,” I said.

“I know,” he said. “If I could part with my children, I’d have real ones. Look,” he said, pointing to his own great bulk. “I’m pregnant all the time. The more I eat, the more children I have inside. They’ll have to remove these with a knife!” He laughed. We all three laughed.

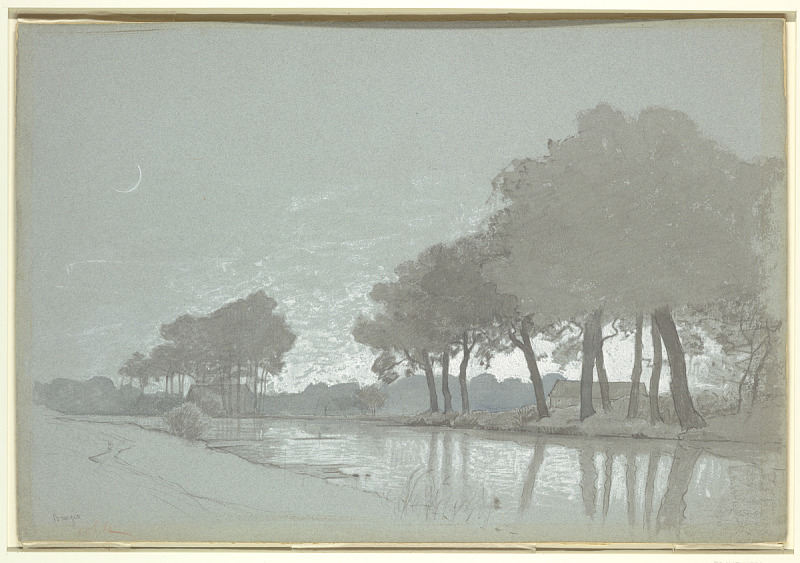

“Come on,” he said, “let’s dance.” He put on wild, whirling gypsy music and reached for a bottle on a high shelf. The bottle had a picture of a plum, and next to it stood a group of tiny, glass carafes.

“Oh no!” I said, when he tried to hand me one. “This I will drop, I’m certain.”

“Ah!” he said, “That’s the beauty of it. When you’ve finished drinking, you throw it over your shoulder. Then you take a new glass. We drink until the corners of the room are filled with shards.”

So we drank, and between the tinkling of tiny breaking bottles, we danced like crazed gypsies. Distantly, at some point, I heard the ringing of my phone; I pretended not to notice, and the other two gave no sign of hearing. I was wild with the excitement of permission to break things.

Suddenly, after about an hour, a terrible thing happened. The sculptor had drunk at least ten of the carafes of plum brandy; he was lurching about. With his enormous hand, he swiped a whole group of his figurines from a shelf onto the floor. “Damn you!” he shouted. “Damn you bloodsuckers, I’m finished!” He started to laugh like a maniac.

“Bernard!” said my friend. “Bernard, stop! You’ll destroy yourself.”

He stared at her like an elephant shot in the knees; then he crumpled to the floor and began to sob. He buried his face in his hands, and the tears flowed through his fingers. My friend went to him, squatted down, patted his shoulders, made soothing sounds. The gypsy music ended suddenly, and in the silence I could hear my telephone. I ran from the room, but before I did so, I swiped two broken figures from the floor and put them deep in my pocket. I kept my hands around them the whole way home to my husband, even though their chipped edges hurt me.

Read More