Florida Man Throws Alligator into Wendy’s Drive-Thru Window

By Mitchell Jacobs

Featured Art: Alligators by John Singer Sargent

The attendant hands him a soda and turns her back, thinking

of straws—how she’s running low, and their candy-red stripes,

and the way everything here comes wrapped up in paper, and

then a 3½-foot alligator is clawing the air.

As if she pressed

the wrong button on the register. Or maybe, during lunch rush,

she’d ignored an oncoming hurricane tossing them about.

In any case, she shrieks, finding for this alligator non sequitur

no earthly explanation. Back when the heavens functioned

with less subtlety, she might have turned to the logic of myth.

The god of rapacity took the shape of a lizard

to penetrate the food hall’s oil-glossed aperture.

Perhaps the oracle of Jupiter, FL on his faux-leather throne

delivers this cold-blooded message to confront corporate greed

teeth to teeth.

Not that the police have succeeded

in extracting a motive. The culprit’s Frosty-smeared lips are sealed.

His charge: assault with a deadly weapon. Yet it rings untrue.

For Florida Man, we need a more particular punishment:

accused of wielding a projectile reptile,

the defendant shall be flung naked

into the Loxahatchee Slough.

If indeed he is a criminal, there will be no proper dunking.

If he is a hero, he will don no duckweed laurel as he rises

from the mud. But the surveillance camera remembers:

it’s not so wide, the gap between the actual and the possible.

About the space from Nissan Frontier to take-out window

where an alligator, bewildered, sees the kitchen’s steam

like fog over a marsh in red bloom, smells the billows

of meaty fragrance, hears the gatekeeper’s yodel of welcome,

and for a moment

flies.

Read More

The Reflex

By Mitchell Jacobs

Featured Art: Boats and setting sun by Ohara Koson

The scent of shampoo reminds me of carrots.

There’s an explanation, I swear, surfacing

from a developing-Polaroid brown. It’s April.

At recess an upside-down pizza slab is gooing

into the cracked blacktop, and a grainy beat

blasts from some girl’s hot-orange earbuds.

On the grass all the boys are playing wallball

with one of those rubber balls like a big pink eraser,

and when I’m up I don’t chuck it far enough

so Austin says, “Come on, Mitchell, you can’t

even throw like the girls,” which is heartbreaking

for a bunch of reasons. Back home, Duran Duran’s

“The Reflex” spins in the Discman on my bathtub rim.

You’ve gone too far this time, and I’m dancing

on the Valentine. My tunes are twenty years out of date

but I know them by heart. I’ve been lying there half an hour,

tub empty, stoking a burn in my gut. Next day in L.A.

(that’s Language Arts), it’s Fat Shawn’s turn at vocab charades

but he just stands there thinking until somebody shouts

“Rotund!” and that’s not his word but it is the end

of the game. That’s how cruelty works around here.

I’m no Shawn but I am Tree Kid and no one

tells me why. The reflex is a lonely child . . .

Jake calls me a poser for wearing skate shoes,

which is how I learn I wear skate shoes, and then

I chase him and kick him with those shoes. Mostly

I’m a head-down kind of kid. I don’t peek at the pull-down map

during the geography quiz. I don’t snicker when

the health teacher says gluteus maximus, but I am

the one who laughs when she can’t spell epididymis.

Another night and it’s the tub again, lights off, interpreting

the song with nonsense lyrics I’m sure have something

to do with all this clench and spasm. The reflex is a door

to finding treasure in the dark. I un-twist-tie

the plastic produce bag and glob out more Pantene, hating

the boys who run around cocksure with their narrow

calves and their throwing arms with actual

visible muscles and those stupid impossible taut butts

and I’ll show them with this soaped-up carrot

what I can take, how it stings, how I tighten my fist

as I hear them spit out my name.

Read More

Love’s Been Good to Me

By Andrew Robinson

Featured Art: Zurich by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

The girl from Zurich is deathly quiet. But even in a king-sized bed her presence prickles me awake. Her fetal body rises, falls, a pillow wedged between us. A natural end approaches now; I’m sure she knows it too. We met six months ago, flotsamed onto the misfit table at a Chinese wedding. There was nothing to do but drink, and seven wines into the night we decided to go slumming at Orchard Towers—Singapore’s neon throwback of tacky sleaze. Sailors go there for the prostitutes, and bankers for the irony, but for her it was the Filipino bands. I love to dance to them, she said, they always try so hard. But she wouldn’t go there without a man, and so, still in my suit at 4 a.m., I held her as she cried on the sticky dancefloor. Cried with drunken empathy for the Indonesian whores she was dancing with. At their age I was still in school, she said, And they have to sell themselves to these fucking men. She feinted at the sweaty marines, bewildered with Burmese whisky and shore leave, and she had me at that. I’ve always been a sucker for compassion—it doesn’t always serve me well.

Then as she sniffed into the smoky bathroom I texted her something about goodness—I don’t remember what—which showed up as her Facebook status the next day. But like the young marines, she was shipping out in the morning, her company posting her to Paris. And it wasn’t until her stint was up—four months later—that we got to meet again. And all that texting and mailing and chatting online, it didn’t serve to warn us that after just a few weeks it wouldn’t be working the way we’d hoped. And now it’s coming to an end—no relish of redemption here—my thoughts rise on a sleepy surge of affection. The girl from Zurich: I’ll remember her—I will.

Read MoreSeafaring

By Marie-Elizabeth Mali

Featured Art: Eddystone Lighthouse by Mary Altha Nims

As if love were a lighthouse and I

the creaking rain-lashed vessel

heaving through the waves.

In the wheelhouse, a heart

that refuses to give up, despite

sharp coral under surface churn

waiting to turn the boat

into a rusted hull the sun vermillions

each morning for photographers

who revel in the sea’s dominion.

I’m tired of chop but don’t remember

calm, the hatches battened down

so long they’re salted shut.

No, that’s not true. That’s someone

else’s story, not mine. I say,

for every hungry ghost in the hold,

ten thousand iron-spined sailors

with rope-calloused hands navigate

around the coral minefields, eyes

on the lighthouse, its revolving beam.

Read More

I Never Met a Flower That Yelled At Me

By Julie Moore

Featured Art: Flowers by L. Prang and Co

her neighbor always says, explaining why,

every year, he plants & hangs

geraniums, begonias, impatiens, petunias,

even blue lobelia, amid his blooming bulbs.

She wants that sentiment to infect her, too,

the summer her husband leaves.

So on the hottest day Ohio can muster, she faces

the roses her husband sank in soil ten years before.

On the side of the house, they grow weed-loud—

even cantankerous saplings push through

the bushes, silencing all the kind words in their red mouths.

Everything has to go.

As she digs, thorns & muscular weeds

thick with prickles recite

her husband’s remarks on her skin,

scratching, clawing, tearing:

I can’t commit to you 100%, only 75%.

Shovel meets hard earth again & again.

Gasping for air, feeling her back spasm in protest,

she clings to the wood handle. You’re too hardline.

You want too much. She lets the sun scold her,

lets the heavy air weigh on her shoulders,

lets all of it, the whole fucking force

of his question—What do you mean I ‘disregard’ you?—

fuel her resistance, her freedom to say,

No, you & your furious mess

will not stand, not here, not any longer.

In their place, she leaves behind

what perennial peace she can—

pink Asiatic lilies, purple coneflowers,

& threadleaf coreopsis shining

their favor without ridicule or question.

Read More

Here Below

By Sarah Carleton

Featured Art: The quadrille at the Moulin-Rouge by Louis Abel-Truchet

Before a careless bulldozer buried him under a ton of dirt

he played with impeccable pulse.

He anchored tunes with a standup bass,

left fingers spidering, right hand patting pauses,

a running commentary that thumped below the chitchat,

bristling with off-color intent.

Just as hothouse plants rooted and swelled

to his sweet, muttered, nasty guy’s-guy nothings,

we set our feet in the soil of his crude jokes and thrived.

His wife didn’t pay much mind to the dirty stories

and sly non-secrets. When he laid their deck,

he penciled women’s names on the underside of the planking,

like an ode to abundance, and she just laughed, shrugging.

We take our cue from her and refuse to fret,

but celebrate him in smut and subtext.

Without crawling among the snakes to check, we hope

we made the list––divas of warm skin and rayon dresses

immortalized on a two-by-ten––

and we also aspire to be like his wife,

who stands aboveboard, rolling her eyes, knowing

her name has been etched more than once in that slatted dark.

Read More

Giverny

By Emily Sernaker

Featured Art: Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies by Claude Monet

I try not to think about falling in love

too much, although sometimes I look

at pictures of Giverny.

You can visit you know.

See Claude Monet’s lily pad garden,

that famous footbridge.

I enjoy a good trip with my girlfriends.

A walk with my sweet mother.

But I want to see Giverny

with my partner. Whom I haven’t met.

Who might not want to fly 3,585 miles

to see a lily pad garden in France,

all of those pastels up close and floating.

Sometimes I check the website

confirming it’s open. That anyone can go.

Read More

Writing What You Know and Whom You’ve Known

Feature: Of Essays and Exes

By Joey Franklin

When I teach the essay to new college students, I usually put the kibosh on three subjects right away—the Big Disease, the Big Game, and the Big Break-Up. One reason for this blanket prohibition is as simple as it is selfish: I don’t want to read bad writing about tired subjects; and there are few subjects more exercised in the essays of new college students than dying family members, fleeting athletic glory, and the pains of first love.

I do have a more legitimate reason for this prohibition than my own desire to never read another internal monologue about teenage unrequited love. You see, I steer my students away from these subjects because, while the loss they represent is certainly real, it is a loss so common as to tax the ability of any writer—let alone a young writer—to say something worthwhile.

Perhaps, then, it is unfair that I follow up this prohibition by challenging my students to write according to Phillip Lopate’s dictum: “The trick is to realize that one is not important, except insofar as one’s example can serve to elucidate a more widespread human trait and make readers feel a little less lonely and freakish.”

Read MoreWhat Binds Them Together

Features: Of Essays and Exes

By Rachael Peckham

When a MacArthur grant-winning poet and classicist writes about her ex-lover, she doesn’t commit a “thick stacked act of revenge” against him, a tempting “vocation of anger” enacted on the page. Yet Anne Carson, author of “The Glass Essay” (from the collection Glass, Irony, and God), knows it’s “easier to tell a story of how people wound one another than of what binds them together.” It makes sense. Where there’s an ex, there’s the story of a relationship—a clear beginning, middle, and the dreaded end, with a natural protagonist in us versus them, the Exes.

That said, Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” which begins with the speaker’s losing sleep over an ex named Law, can hardly be called a clear or easy break-up story. In fact, it’s not a story at all but an essay in verse—one that doesn’t mention him much. Perhaps it’s no surprise that it’s not about him (is it ever, with the essay?) but about her. About several hers, actually; Carson oscillates between “three silent women” each struggling, each alone or left behind in love. It’s loss that binds them together.

Read More

Breakup, Break Down, Break Open: Intimate Partner Violence and Life Inside a Daily Ending

Feature: Of Essays and Exes

By Sonya Huber

Some relationships fall apart in a gradual and mutual cooling, and others rise toward a crescendo of irreconcilable differences. Still others are threaded with periodic or daily heartbreak and even violence. Imagine living a love in which every moment was a breakup, and every next moment was a reunion, over and over and over. The essay of domestic violence is the essay of a living bonfire of a breakup, an extreme breakup in slow motion, and in this writing we can see essayists shining a light on heartbreak, but also on thornier issues of identity and personal safety.

Many of the best essays in this genre have to deal with misconceptions about domestic violence first, since the query applied to an abused person in a relationship is often: “Why didn’t she leave?,” why wasn’t a simple breakup the solution, as if the abused had a decision to make and then failed to make it correctly. For some people affected by domestic violence, though, the breakup hovers as a longed-for destination, an impossible shore to reach. Others fear the breakup due to real hazards and the effects of trauma. And so the question reveals the asker’s naiveté. The nature of violence is that it won’t simply be left. Violence pursues, damages, threatens, and changes the reality that contains it. Several notable essays have dealt with this painful truth.

Read MoreMore than a Vanished Husband: Jo Ann Beard’s “The Fourth State of Matter”

Feature: Of Essays and Exes

By Holly Baker

“My vanished husband is neither here nor there,” Jo Ann Beard writes in her 1996 New Yorker essay “The Fourth State of Matter.” She’s describing a relationship caught in the freeze-frame of a collapse. The rafters have buckled and the walls are caving in, but the marriage structure is falling, not yet fallen. Beard, though, is not centrally concerned with the catalyst of this disaster, nor its aftermath. She does not reflect on settling dust or salvage work. Instead, with a sense of foreboding, her essay captures the days and hours preceding a series of inevitable tragedies: divorce, the death of her dog, and a horrific campus shooting that leaves seven people dead and a survivor seeking new self- definition.

Beard’s lack of control over these horrible intertwining events permeates the writing, and her failing marriage hovers continuously and gloomily in the background as she thinks about her “vanished” husband. But why vanished? Why does Beard paint him this way, not as estranged or simply gone, but vanished?

In this word, she seems to want to elicit a magic trick, and readers may just as well finish the phrase in their minds: vanished without a trace. Unexamined and unexplained—this is exactly the approach Beard uses to distance herself from the heartbreak of impending divorce, from allowing herself to mourn a relationship that has died. To spare herself and the relationship from bare examination, she instead creates buffers and barriers as tools to cope with and contextualize these losses.

Read MoreOn Breaking Up with the Dream of Your Former Self: Megan Daum’s “My Misspent Youth”

Feature: Of Essays and Exes

By Kelly Kathleen Ferguson

We all know “you can’t go home again,” but what does it mean to long for a place we’ve never inhabited, to love that idea so much that it feels like the beginning of a relationship? And what does it mean to finally admit defeat and break up with that ideal?

Megan Daum, in “My Misspent Youth,” writes of her infatuation with—and split from—New York City, and her long-cherished imagination of the life she would lead there. Daum begins by recounting a time in high school when she first saw a couple’s artsy, romantic Upper West Side apartment. From that moment she was driven by an “unwavering determination to live in a pre-war, oak-floored apartment on or at least in the immediate vicinity of 104th Street and West End Avenue.” Daum goes on to detail how this obsession influenced every major decision of her late teens and twenties, until she discovers—as in most relationships—there’s no escaping money trouble.

Read MoreOn Natalia Ginzburg’s “Human Relations”

Feature: Of Essays and Exes

By Dinah Lenney

“ . . . the friend we’ve dropped is hurt on our account . . . We know this but we have no regrets, indeed we feel a kind of covert pleasure, for if someone suffers on our account, it shows we have the power to cause pain, we who for so long felt utterly weak and insignificant.”

So writes Natalia Ginzburg in “Human Relations” in which she considers the way people come together and grow apart; and come together and grow apart; not a breakup essay exactly, and yet it will serve, I think, I hope, since Ginzburg breaks (or anticipates breaking) with parents and friends and relations from beginning to end. She hangs her reflection-on-the-human-condition (that’s what this is)—in which we humans are eventually forced to come to terms with how human we are (as in helpless in the face of the universe, as in doomed from the start)—on a story of coming of age, beginning in childhood when we are understandably baffled by adults and their “dark and mysterious” ways. Next, sparked by adolescence, comes the long middle of the piece: Enamored of our peers, Ginzburg admits “we punish the adults . . . by our profound contempt”; by the end of the essay, she herself has grown up, of course. “We are so adult now,” she tells us, “that our adolescent children are already starting to look at us with eyes of stone.” In other words, what goes around comes around, right? As for what happens in between: Relationships—hers (ours?)—keep ending and ending and ending of natural causes, which (if we don’t count death) only means we eponymous humans—naturally (hopelessly) fickle and self-serving—are to be held responsible more often than not.

Read MoreNew Ohio Review Issue 21 (Originally Published Spring 2017)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

Issue 21 compiled by Averie Hicks

Push

By George Bilgere

Featured Art: by Clay Banks

I’m trying to look as if I’m suffering.

I have this anguished expression on my face

but it’s wasted since I’m wearing a surgical mask

and anyway the focus here is really on my wife

and the doctor is right there between her legs

and he’s shouting Push, and my wife

is doing this astounding thing, she’s pushing

yet another human being into the world, a world

that so far seems to be pushing back,

and the baby’s heartbeat is down to 90

so the doc says, I think maybe one more try,

then we do the Caesarean, so things in the room

really are a bit tense, it’s definitely a moment

that demands a lot of attention, and my wife

is gathering whatever shreds of strength

remain in the shaking exhausted sleeve of flesh

her body has become, the blood and sweat and fluids

everywhere, and this is It!—when I hear

the attending nurse standing just behind me

saying to this guy in scrubs standing next to her,

I think he’s the anesthesiologist’s assistant,

Well, just because Karen says she has a boyfriend

doesn’t necessarily mean she won’t go out with you,

and the guy says, his voice rising because my wife

really is screaming quite loudly at this point,

Yeah, OK, I guess I should give it a try, I mean

what’s the worst that can happen, other than

getting shot down and looking like a total fool,

and the nurse says, as the doctor is shouting PUSH,

Yeah, but hasn’t it been like a long dry spell for you?

Aren’t you getting a little desperate here? And the guy

laughs and my wife screams again and the doctor

says Yes and into the world comes the bloody head

followed by the naked lovely bloody little boy

insanely ill-prepared for any of this, and I guess

the guy actually is going to ask Karen out

and I say go for it.

Read More

Void Unfilled

By George Bilgere

Featured Art: Long Exposure Couple by Jr Korpa

I walk past Erin’s house at dusk

and there she is at her kitchen table,

working on her book about the Reformation.

She needs to finish it if she wants to get tenure,

but it’s slow going because being a single mom

is very difficult what with child care and cooking dinner

and going in to teach her courses on the Reformation,

which I can see her writing about right now,

her face attractive yet harried in the glow

of her laptop as she searches for le mot juste.

Meanwhile Andrew, her nine-year-old son,

shoots forlorn baskets in the driveway

under the fatherless hoop bolted to the garage

by the father now remarried and living in Dayton,

as Andrew makes a move, a crossover dribble,

against the ghost father guarding him, just as I did

when I was nine, my daddy so immensely dead,

my mother inside looking harried and scared,

studying thick frightening books for her realtor’s exam.

And although I hardly know Erin,

I feel I should walk up, knock on her door,

and when she opens it (looking harried,

apologizing for the mess) ask her to marry me.

And she will smile with relief and say

yes, of course, what took you so long,

and she’ll finish her chapter on the Reformation

and start frying up some pork chops for us

as I walk out to the driveway and exorcise

the ghost father with my amazing Larry Bird jump shot,

and tomorrow I’ll mow the lawn and maybe

build a birdhouse with the power tools slumbering

on the basement workbench where the ghost

father left them on his way to Dayton.

I will fill the void, having left voids of my own,

except that my own wife and son are waiting

down the street for me to come home for dinner,

and so I just walk on by, leaving the void unfilled,

as Erin brushes her hair from her face and types out

a further contribution to the body of scholarship

concerning the Reformation, and Andrew

sinks a long beautiful jumper in the gloom.

Read More

Horseplay

By George Bilgere

Featured Art: Abstraction, 1906 by Abraham Walkowitz

I am floating in the public pool, an older guy

who has achieved much, including a mortgage,

a child, and health insurance including dental.

I have a Premier Rewards Gold Card

from American Express, and my car

is quite large. I have traveled to Finland.

In addition, I once met Toni Morrison

at an awards banquet and made some remarks

she found “extremely interesting.” And last month

I was the subject of a local news story

called “Recyclers: Neighbors Who Care.” In short,

I am not someone you would take lightly.

But when I begin to playfully splash my wife,

the teenaged lifeguard raises her megaphone

and calls down from her throne, “No horseplay in the pool,”

and suddenly I am twelve again, a pale worm

at the feet of a blonde and suntanned goddess,

and I just wish my mom would come pick me up.

Read More

I Tie My Shoes

By George Bilgere

Featured art: ‘Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity’s Gate)’ by Vincent Van Gogh

I’m walking home late after work

along Meadowbrook Road when I realize

the guy half a block ahead of me

is Bill, from Religious Studies.

I recognize his bald spot, like a pale moon

in the dusk, and his kind of shuffling,

inward-gazing gait. Bill walks

like a pilgrim, measuring his stride

for the long journey, for the next step

in the hard progression of steps.

And while I like Bill, and in some ways

even admire him (he wrote something important

maybe a decade ago on Vatican II),

I slow down a little bit. I even stop

and pretend to tie my shoes, not wanting

to overtake him, because I’m afraid

of the thing he’s carrying, which is big

and invisible and grotesque, a burden

he’s lugging through the twilight, its weight

and unwieldiness slowing him down,

as it has for five years, since a drunk

killed his teenaged son, and Bill’s bald spot

dawned like a tonsure and his gait

grew tentative and unsure, and his gaze

turned inward as his body curled itself

around the enormous, boy-shaped

emptiness, and the question

he spends his days asking God.

And if I caught up with him

and we walked together through the dusk

he would ask me about my own son,

who is three, and the vast prospect of the future

onto which that number opens, involving

Little League and camp-outs and touch

football in the backyard would hang there,

terrible and ablaze in the autumn twilight,

and the two of us would have to slog

down Meadowbrook Road like penitents,

adding its awful weight to the weight of his son

on our backs, our shoulders, and so I fail

Bill, and stop and pretend to tie my shoes.

Read More

Facebook Sonnet

By Tanya Grae

Featured Art: by Prateek Katyal

Someone thinks I’m beautiful again

& likes posts of my day, comments.

I stifle smiles & feel uncontainable—

bungeed off ether & the interplay.

Punch-drunk in this blue-sky space,

a rush of the past, the in-between,

whole chapters, I open annuals

& albums from storage. His change

in status: single. Papers in hand,

this backlit man heaves toward

the kite’s trailing end: What if?—

that butterfly. My youngest lights

onto my lap. Who’s that?—

as a key turns the lock, I log off.

Read More

Your Mother Wouldn’t Approve

By Krystal Sanders

Of the way you spend Saturday morning in your room, instead of helping Papaw with the lawn work. You watch him on the riding mower, in customary slacks and suspenders, coasting back and forth beneath your window as if the ragged scream of the machine will summon you like a siren to your manly duty. You raise the binoculars Papaw used when he was stationed in West Africa during WWII, long before his shoulders bowed and his skin darkened with liver spots. They are clunky, large in your hands even though you’ve had a growth spurt and you’re well on your way to catching up to Peter, who’s a whole six feet and had college basketball scouts watching him at every game last season. It was Peter’s senior year of high school, your freshman year. The fall had been glorious, riding the cloud of popularity as Peter Thompson’s younger brother. The other kids, the teachers and coaches, cafeteria ladies, librarians, all looking at you with an expectation that was not yet a burden. You joined the Fellowship of Christian Students, which Peter was president of, and took the Advanced Placement classes he’d taken. You had more friends than you’d ever had before. Through the lens, Papaw’s face jumps up at you. You’re intimately aware of every wrinkle, every nose hair. He guides the mower in long, straight lines, first in front of your window at the corner of the house, on the second floor, and then away toward the county road. The motor’s howl falls to a low growl, builds back up as he returns exactly two feet to the left, is eventually reduced to a low grumble at the back of the house.

Your mother wouldn’t approve of the way you watch the world, binoculars pressed to your face, aimed into the neighborhood across the county road. The man who owns the nearest corner lot, 5371, has some kind of shepherd. The dog roams along its chainlink fence, pants in the heat, takes a shit. You catch a glimpse of motion deeper in the neighborhood and sit up straight. You focus on the door that caught your eye, at 5377 striding out of the back of her house in shorts and a man’s plaid shirt. She is headed to the metal trash barrel at the back of the lot. You know she will stand there for a long time, and then go back inside. You imagine burying your fingers in the tangle of her long hair. She is barefoot, and the thought of the stiff crunchiness of the yellow grass against the tender arches of her feet almost makes you moan.

Read More

The Worn-Out West

By Pamela Davis

Featured Art: by Jannes Glas

I drive past motel signs advertising

free cable for bikers, truckers numbed

by cracked asphalt. A looseness,

as if everything is slipping

away, and the sky shaved thin as mica.

Stretch of dusty storefronts hung

with local art—warriors astride

painted horses, mesas. The Rio Grande

cuts in and out, shape-shifting

between cottonwoods. In the café,

regulars remove their hats, sit alone.

One gathers himself judge-straight

as the waitress refills his mug,

her bar rag slung over a bare shoulder.

She gifts him a sudden, chipped-tooth

grin. Yesterday she banned

a drifter for fouling the toilet she lets

everyone use. Today she walks a cup

of coffee across the street for

a homeless guy wrapped in his own arms.

On her own this young, every new boss—

town, lover—will treat her like a stolen car.

Smooth, how she glides

from radio to grill. Easy, her talk,

comebacks quick. And outside, a mountain

looms, split long ago by a blast. Wire mesh hugs

some of it back. I want to tell her temporary

lasts a long time. The air is thin

up here. It’s nobody’s idea of home.

Read More

What My Massage Therapist Girlfriend Discovers When I’m On Her Table For the First Time

By Robert Wilder

Featured Art: ‘Avocado’ (1916) by Amada Almira Newton

Your right leg is shorter than your left.

There’s something funny happening in your left shoulder.

You should change your detergent and go fragrance-free.

Is this too much pressure?

You once had a girlfriend who threw bottles at your head.

You haven’t slept well in decades.

You store all the grief for your dead mother in your solar plexus.

Breathe.

You grind your teeth.

You have the musical tastes of a seventeen-year-old girl.

There’s tension in your neck which runs down your left side.

No one believes that you are not attracted to Rebecca.

Does this hurt?

Let me stretch you out a bit more.

For someone with such little flexibility, you have a surprisingly good vertical.

You’ve wounded more people than you’re willing to admit.

Your father will die soon and you’ll have no clue where to turn.

You and your brothers will drift apart.

Sorry about that. Just trying to break it up.

Nothing will get easier for a long time.

You loved the bottle thrower something fierce.

You can’t hear your mother’s voice anymore.

Turn on your side, please.

You still love the sun sneaking through cracked windows.

You have a closet full of clothes that no longer fit.

Holding your breath won’t help either of us.

There you are.

Read More

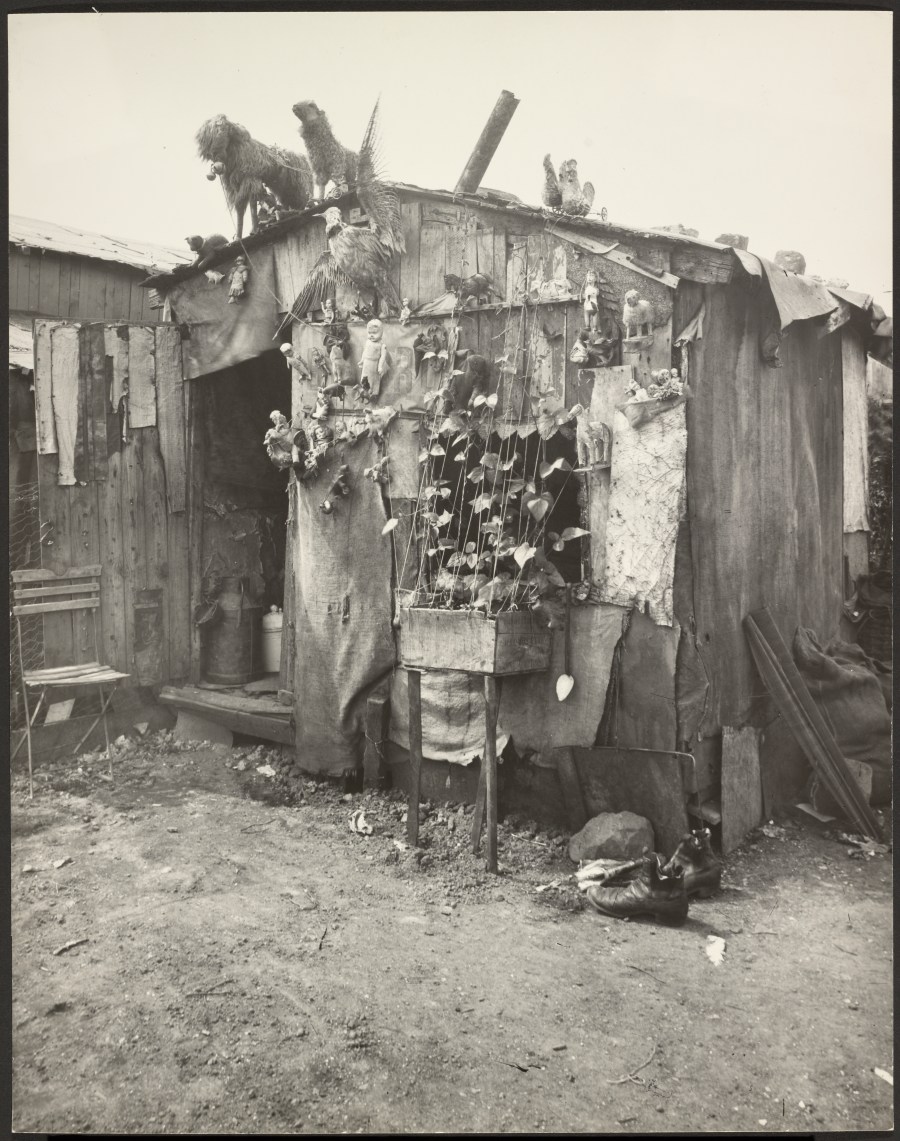

Stuff

By Claudia Monpere

Featured Art: [Villa d’un Chiffonier (Ragpicker’s Shack)], 1920 by Eugène Atget

I saw you, daughter, sneaking

a garbage bag of my treasures

into your car. Those heaps of eyeglasses are art.

Never mind the cracked lenses

and broken hinges, the bent frames.

Some day I’ll make a sculpture or hanging lamp.

I’ll make a mobile.

The broken picture frames and dried-out

pens. Even the bottle caps beg

to be known. And how patient

those stacks of hotel soap.

Waiting. Just in case.

Yes newspapers haystack the walls.

But it’s all there: knowledge at my

fingertips. The postman will bring more.

There is an ocean liner inside my heart

that waits to set sail. The crowds wave

at the dock. My shades are drawn.

Bring me, daughter.

Don’t take. Bring me a basket

brimming with words.

Not fester, not filth—

fang words that surgeon my heart.

Bring me gossamer, lagoon, violet-crowned

hummingbird.

Bring me, daughter, elixir of cloud.

Read More

A Race Car Made of Sand

By Margot Wizansky

Featured Art: “Beach of Bass Rocks, Gloucester, Massachusetts” by Frank Knox Morton Rehn

Everything made my mother nervous:

the baby crying, sand on the floor, the flies.

So we went out to the beach.

I took my bucket and shovel.

My mother sat my little brother up on her shoulders

and carried the towels and a canvas chair for my father,

who was too weak to carry anything.

He wore his cabaña suit, light green with white palm trees,

his legs, pale like the sheets in the hotel room.

He hadn’t shaved.

His face had been blue for weeks,

the circles under his eyes, dark as his beard.

Mother said I was too heavy to sit in his lap.

All afternoon I dug a string of frantic little ponds.

Nothing was right; my back was sunburnt;

my father hardly moved.

Uncle Robert came, like a bus from the city,

to build me a race car of sand, with jar lids

for hubcaps and for headlights, clamshells,

and he found a quoit on the beach for the steering wheel.

He dug me a driver’s seat that just fit,

and a rumble seat for my little brother.

My father peeled me an apple with his penknife,

in one long piece, that didn’t ever break.

Read More

Some Things Rosa Can’t Tell Little Esmeralda

By Barbara de la Cuesta

Featured Art: by Farrukh Beg

A late afternoon after work, Rosa puts the flame down under the rice and beans and sits with her feet up in Laureano’s recliner. The knock on the front door Rosa thinks must be Mondo’s social worker, the only person she knows who doesn’t just walk in the back door. Mondo is in detention again for defacing a wall, or an overpass, something.

But it isn’t the social worker, it’s little Esmeralda, daughter of the Mexican grocer on Moody Street, who comes in politely, sits opposite her with a notebook, and asks Rosa can she ask her some questions. Hah, like the social worker, Rosa thinks, then corrects herself. This is a child she used to see sitting on the floor of her father’s abasto sorting red beans. The girl tells Rosa she needs to write a biography of an older person for her fifth grade class.

Ah, Rosa, with her aching feet, feels old.

Not old, old; just older than me, says the child. She used to be in Rosa’s catechism class at St. Justin’s and was notably better behaved and brighter than any of the others.

Hokay, says Rosa, not yet realizing what will happen to her.

Read More

Miles

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by Mike Lewinski

It was dark, sure, but the city’s halo

whitewashed the stars.

We drank good bourbon from Dixie cups

to mock our sophistication.

Two black men and a white one

who needed a brother.

We drank to Ghana advancing,

not so naïve to believe

they had a chance against England.

We toasted our wives of many colors

and our barefoot children chasing fireflies

like the first night in Eden.

But it was Oakland.

So when the boy climbed the porch steps

cupping a winged and glowing offering,

I called him by the wrong name, as if

I did not know him, as if his father

was not my friend.

The brothers exchanged their look,

too polite to call me out

on a summer night in paradise.

And we all pretended not to notice

the bats that let go their roosts

to flap old patterns in our chests.

Suddenly I felt like humming

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” professing my love

for Serena, telling them all about my black Scout leader

whom I hadn’t thought about in years,

assembling, in other words, my own minstrel show

to prove how down I am.

All the while, the party soundtrack plays on

through hidden speakers, Kind of Blue

from the end of that gorgeous terrible horn:

Live, no net, each note feeling its way

into the dark as if we can still improvise,

as if there is always another chance

to get it right before the night ends.

The boy, who isn’t Miles after all,

keeps coming closer

to show me his gift, opening the dark

hemispheres of his hands so I can see

the pulsing fireflies lift off

to join the others in the city’s halo

far above our heads.

Read More

Mitigation

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by Romina Farías

Somehow it’s good to know

the wildfires have not touched the face

of our local TV anchor

delivering her lines

with a touch of sadness that never approaches

despair, even as her bangs cascade

onto her forehead like evening clouds

descending the Coast Range.

I think of her in her dressing room

before she offers her face to us—

the one that will help us fall asleep—

while a line of flames somewhere far away

descends the ridge and licks into a kitchen,

melting the refrigerator magnets,

popping cans of spray oil, and setting

the dog out back to howling, jerking

against its chain.

I see her in front of the mirror,

surrendering to the ministrations of tiny brushes—

a makeup artist leaning in like a lover.

Foundation first, an A-side attack

on brow furrows and laugh lines.

Then concealer to suppress the advance

of crow’s feet into the Botox buffer zone.

Within a half-hour, the spread of creases

and fissures 95% contained.

The brushes flit across her face

like prayer flags, and I can almost smell

the warm breath of the girl who sticks out

the tip of her tongue, leaning close

to line the boundary

where the fullness of a lower lip

begins its concave plunge

into smooth white chin.

Our TV anchor practicing her lines,

mastering her face.

We need to love her for this.

For the way she shows us how to keep

a chin from trembling, an eye from twitching

even while the chained dog

curls in on itself in the burning.

Read More

Parrots Over Suburbia

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by McGill Library

There are two,

as if some ark came to rest

on the high school football field

and Noah flung them through an open window

to test whether this cement-skinned town

can sustain life.

See them there, trimming

lava-dipped wings in the sky above Costco,

bills curved like question marks.

And what do they ask, out of earshot

of the man with sunflower seeds?

Do you know what it means

to circle, to draw and redraw the tightening

circumference of your life

above the grid of 50-year roofs,

in steak smoke risen from backyard barbecues?

The parrots’ owner is no prophet.

Summer evenings, he wrenches

on a ’67 Mustang that drips its innards

onto his Avenue L driveway.

And at dusk, he makes his arm a perch,

takes the two from their cage,

feeds them from his lips, knowing

if they love him he need not maim their wings.

So they fly in circles

and on every pass above the fenced playground,

swoop near to watch the girl in high-tops and earbuds

swinging, head thrown back to reveal

her pale and wild throat.

Read More

Steno

By Mark Kraushaar

“Hypergraphia is a behavioral condition

characterized by the intense desire to write . . . ”

“It is a symptom associated with temporal lobe epilepsy.”

It’s as if . . . , he says, It’s like . . . , or, It’s ABOUT

things being simply THERE, molecular,

blue, strewn, flattened, aflame.

He pulls up the shade and looks out.

There’s this kind of accounting he does:

sidewalk, hedgerow, phone pole.

He lists the round and the ready-made.

He notes the hand-carved and the curved.

He sorts by color and shape.

He lists by size and by brightness.

He notes the nautical, normal and nameless.

It’s Wednesday and he’s moved from columns

to rows: alphabetic, magnetic, majestic . . .

He lists the unowned and the changed,

the charged, unsuitable and smooth.

He leans forward turning the page.

It’s like . . . , It’s as if . . . , he says,

as if these THINGS, this STUFF:

hunk and clod, object and article, gizmo,

whatnot, doodad, exactingly placid, substantial

and actual, for knowing nothing,

know it all: guruish shoe-tree, savvy axle.

He opens the door and sits on the stoop.

It’s as if each thought over-laps the last.

A girl on a bike goes by.

Read More

Fable

By Sally Bliumis-Dunn

Featured Art: Formerly attributed to Zhao Boju (ca. 1120s-ca.1162)

People often spoke

about her mousy behavior,

her gray squeaky voice,

but no one made the connection

that the words they used,

which she devoured like giant crumbs,

commenced her change,

so that when she drew the curtains

to darken the air

it was not a sign of depression

as they had begun to suppose

but simply a trait as she became

more and more nocturnal,

scurrying about the rooms, the tail

of her housecoat trailing.

Read More

Safehouse

By Sandy Gingras

Featured Art: by Pierre Châtel-Innocenti

Pull up any rug, there’s a hole.

An easy chair sits on a trap door, which leads to

a slide. I am still surprised, after all these years,

how many tunnels are in my house.

In the basement, which is under the place

you would consider the basement, is

what I call “the secret room.” But all my rooms

are really secret rooms. It has a large

colored map on the wall, a folding table under

a fluorescent light, a red couch.

I go down there to find

a way to slip something into my dreams or to

block my escape routes. I am a spy, don’t

you know? I don’t look like a spy, and I’m paid

nothing for my work, but I do it anyway.

I was called, as they say, to duty.

Under my clothes, I’m naked.

Within my ID card is another identity.

I can change at will. I have a machine

that scrambles my words into code,

a pill I can bite to shift my mood,

a certification to never sleep.

Now I must run.

Even though there is no such thing as a

hiding spot in this house. Even if I put on

my invisible suit. Even if I cover my face

so I can’t see myself.

In the bathroom cupboard is a shelf that lifts

to reveal a chute which looks like it’s for laundry,

but it isn’t. I can’t hear when I hit bottom.

Read More

Other People’s Ranch Dressing

By Kate Maclam

Featured Art: by Au Lido Plate no.14 (1920)

I wanted to smell less like

a restaurant and more like

a woman.

I tried my best.

All the women I know could

have sex with famous men

like J Hamm or Leo D or BJ.

All the women I know smell like

French Vanilla perfume

and fresh cigarettes.

They smell like thin people.

When I describe them I say,

she is thin like a rich person.

I say, she eats paper

and melts diamonds,

to stay thin—

she huffs paint thinner.

I say, she has never touched

another person’s ranch dressing

or brushed it onto her thigh

where it looked like

the seed of a famous man

or anyone really.

Read More

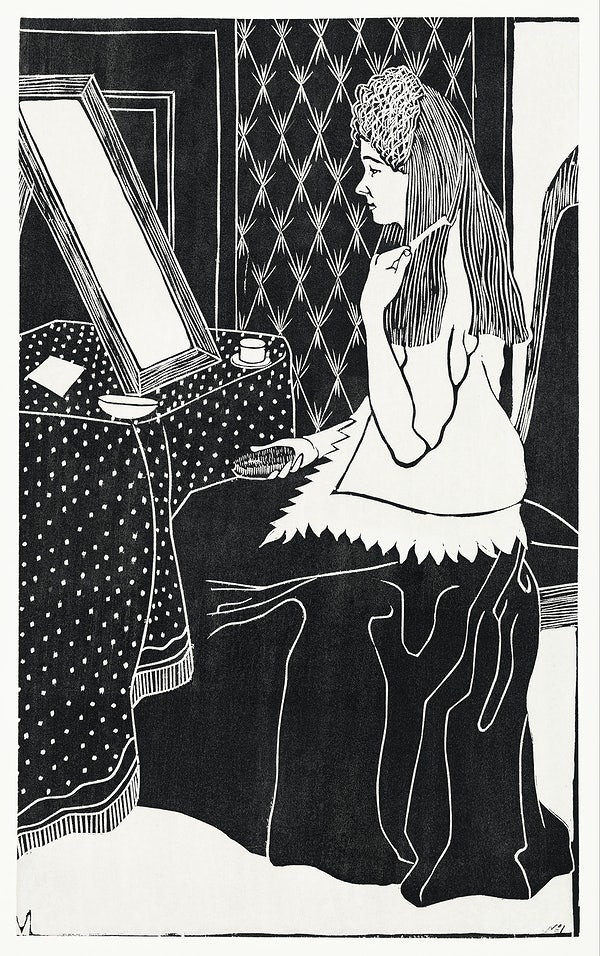

Nightmare on Elm Street

By T. J. Sandella

Featured art by Vrouw aan kaptafel

Though they’re meant to be our protagonists,

we detest these teenagers

who fall for the same tricks and traps

in every film

and because they keep coming back

dumber and hotter

decade after decade

with their perky breasts and discernible abs

and the way they throw themselves mercilessly

against one another

in backseats and on twin beds

and because they smoke cigarettes

and slug soda and beer

and because dialysis and diabetes

will never creep like Freddy

into their dreams.

Because they’re always in love

and loneliness is as unimaginable

as feigning sleep

so the person next to you

will stop kissing your neck

though you still care for her

and he’s still beautiful

or maybe you don’t

and maybe he’s not

or maybe the workday has emptied you

of desire for anything

but seven hours of silence

and maybe these are the words you say

that can’t be forgiven. Curse the children

for not knowing

that if you live long enough

life is mostly washing dishes

and may they suffer

for not believing

that young love dies

when the first person

goes to college

and meets a sorority girl

who can put her legs behind her head

or the backup point guard with the bulging

biceps. Twelve bucks is a bargain

to see these brainless babes

pierced by pitchforks, their chiseled flanks flayed

and hung from hooks. It’s because

their failures will never grind them

into something so small

that they’ll go to a theater alone,

buy some popcorn, and sit in the glow

of another slasher reboot, trying to distract themselves

from their disappointing lives.

Loving by Numbers

By Frances Orrok

Featured Art: by Nick Fewings

10

my dog, climbing trees, apples, my sister

On two separate car journeys, one with my mother, one with my father, I ask each of them to choose the last thing they’d give up. At ten, my questions take this form with some regularity: exaggerated parameters, carefully explained rules. “It can be food or water or something solid, but it doesn’t have to be. You only have twenty-four hours to live.” Both ask if they can think about it. Both remember to answer by the end of the journey (a hastily added rule).

My father: “the capacity to love.”

My mother: “to know I am loved.”

11

anywhere outside the classroom; mud, cold, leaves, not sports, lists

I start smoking in ditches. I ask my father if he’d still love me if I went to prison. “Of course.” He doesn’t hesitate or ask what crime I will have committed. I think about this and watch the back of him digging. I don’t doubt his words but I am curious. “What if I joined the IRA?” There is a long pause and he straightens out for it. The Irish Republican Army is in the news a lot. They drive fear into every school child, make public transport and Saturdays anxious. There are no longer bins on the streets, litter blows frightened of b-o-m-b-s. “There will always be things you could do to make loving you harder. That’s not the same as not loving you. Difficult doesn’t mean no.”

Advice

By Emily Sernaker

Featured Art: by Fran Hogan

Don’t ever make him a take-me-back

mix CD. But if you do, open with Sam Cooke’s

“Bring It On Home To Me.”

If Kim from high school wants to wait

in the really long line for the panda

at the zoo, don’t complain.

That panda is going to be so cuddly cupping

its paw around the bamboo, your heart

will do a somersault. Besides,

you’ll miss Kim when you’re away

trying to tell her updates

before the metro goes underground.

“I’m going on a date and wearing eyeliner.”

“You’re going on a date with a minor?”

Distance can be so hard. If you take

a dance class at the gym don’t stand

in the very back. Halfway through they turn

around and that side becomes the leaders

of the choreographed dance

everyone knows but you. You want

a middle-back spot for minimal shame.

One more thing about boys—

sometimes they’re sending a message

by not sending a message. There are many

films and books about this. If you need

an easy Halloween costume

go with Clark Kent. You just wear

glasses, a button-up shirt, a loose tie,

and show a Superman logo

underneath. You can even make

a Daily Planet badge if there’s time.

That noise you hear in the morning

opening the coffee shop isn’t

the other barista sneezing.

It’s the espresso machine warming up—

you don’t need to say bless you.

Ask your mom how she’s doing. Early

in each phone call ask her and really listen.

If you don’t, she’ll let you talk and talk

and what kind of person

do you want to be? You should

probably read Dante, that gets referenced

a lot. Anyone who hates Bob Dylan,

especially the Blood On The Tracks album,

is wrong. He’s given us a road map

to life, they should be grateful.

One last thing—don’t be scared

when the Georgetown cross-country team

is running toward you full speed

on the bridge. I know

it’s the bridge with the narrow walkway

close to traffic, where there’s nowhere

for you to step to the side.

Just raise up both of your hands.

Sixty people will give you high-fives

and keep going.

Read More

Mawwage

By Catherine Stearns

Featured Art: Rising Dove, 1934 by Harold Edgerton

Mawwage is what bwings us together.

—The Princess Bride

At five, a clamorous bird

proposed outside our window:

Will-ya will-ya will-ya, then?

when a high-pitched vireo

like a shotgun bride

interposed fuck-you fuck-you

before his liquid goddess

could reply, with a flirty little

who-me who-me? followed by

something like my mother’s

tch-tch-tch-ing at my father’s

stories she’d heard a million

times before, nattering

away as if strapped on

currents of confused desire,

but finally speeding up

to an ascendant trill—I do

I do, I do / aspire to—

broken off by our alarm clock’s

insistent beep. Aspire to . . . ?

Aspire to . . . ? Happiness?

Transcendence? Sleep?

I turned it off to hear

not the long-married coo

of doves I often do

upon waking, but the shameless

heart of a bird

quivering in song

that knows itself alone

except for you, afloat

among the highest shelves

of dark and light, singing

and singing the changes through.

Read More

Marriage at 17 Years

By Gary Dop

“Come here—quick!” You know it, her serious, nearly

whispered call. She says, “I think it’s a squirrel.”

Brown bulb of fur, it’s tucked behind an old chair.

The kids sleep upstairs; you have both abandoned

your evening’s screens. You are here,

a step away from a baby flying squirrel. You grab

the wicker hamper. She says, “Don’t scare it.”

Hamper in one hand, towel in the other, you wonder

how to catch it without scaring it. The big-eyed squirrel

knows you’re there. “Be careful,” you hear as you swipe

at the squirrel who scampers, fast as life,

into the wicker trap you lift and close.

Then she says, “It’s in there,” a statement of fact

that feels like a question. You say, “It’s in there,”

your voice an octave too high. She peeks through

the wicker gaps to snap a picture. You relax

your grip on the lid, and the wild thing wriggles free.

You scream. She smacks you

upside the head, a gentle reminder of the hibernating children.

You both scurry after the squirrel

which seems so scared until it’s near the stairs—

then it’s a feral beast between you and your offspring.

With animalistic ease—her leap and block, your swipe

and scoop—the rodent’s back in its cage,

and you’re out on the sidewalk, clutching the hamper,

waiting for your neighbors—just pulling away—

to be far enough not to see your business. You both smile

and wave too easily, like stoned teenagers startled by cops.

A moment later, the flying squirrel is off:

The thing that just happened is over.

And you are outside, suddenly together.

Read More

The Double

By Gary Dop

Featured Art: by Tim Mossholder

When I order fast food, I feel superior

to the place I am in, the people

who serve me, and the grease

about to grip my gut, but

the cashier asks “Is that poetry?”

pointing at the distressed volume I hold.

I say, “Yes,” and she says, “Yes,

I thought so,” her eyes bloom,

no longer machines. Her hand rests

on the input screen as she quotes Frost

or Dickinson: something about “long sleep,

a famous sleep,” and she adds, “Was ever idleness

like this?” Flustered, I reply: “I’ll take

the double with mustard and pickles.” She sees

into me, a mass-produced poetry patty

stamped for the look of flavor. She sees

my surprise and knows that beneath our exchange,

burger for cash, is deeper change:

The life I’ve slept inside, she takes, discards,

and watches me wake.

Read More

Red Beans and Rice

By James Sprouse

Featured Art: ‘Modes et Manières de Torquat‘

The medium said you were not coming back.

So I ate my red beans and rice

same as on our wedding day

down in Algiers, Louisiana.

The next day you rode

off with the Russian, Porshenokov,

in a little MG, your long straw hair

whipping in the streets

in the wind of the French Quarter

and down on the bayous, where it’s

too hot to sleep. The cemetery on Ramparts

was a forest of stone, the dead

above ground. On account of

the hurricanes, they said, and high water

on the Mississippi that stirs underneath

and raises them up.

That time you came back,

in heat, in sweat, with cotton-mouth

and juju. The South was our

time to be hot.

Next day you shipped out

lithe as a dolphin

rolling and tumbling down to the delta

on whiskey and water we called our lives.

Beautiful dreamer, awake unto me . . .

on Lake Pontchartrain, in the boat

of our nights, your prodigal smile

alive with fabulous poison.

Read More

Year of the Rat

By Lucas Church

Featured Art: Chinese Zodiac Animals in Harmony by Kerima Swain

On my birthday, the twenty-fifth anniversary of a space shuttle disaster, I move in with Uncle, who lives next to a trash heap. The heap is privately owned, not the county dump, not open to just anybody, and it’s haloed with crows. I squirrel myself upstairs while Uncle watches the video of the spaceship disintegrating into smoke, repeating. I mention in passing an ex-boyfriend with fists like cans of beans, that he’s looking for me, probably. Outside the crows bicker while I hide under the covers, the house full of Uncle’s sobs back to the television.

The shuttle exploded hours before I was born. A question of timing, my mother said.

Fast forward to our routine each morning: Uncle sloughs to the door and asks if I am okay, if I need anything. I always say no, but offer to clean his pool, where trash from the heap sometimes catches. Uncle doesn’t ask about Ex, though he’s gleaned I’m running from Ex’s jealousies and agendas, but rattles out something about decisions, good and bad, where they end us all up.

After weeks of this dance, he finally needs something: We lack pudding. Uncle has a sweet tooth. Or maybe we could go for dinner, he says, talk about things, hit some of the friendly bars, etc. Two guys on the prowl then silence and we all feel embarrassed for him together.

Read More

My Mother’s Dogs

By Sandy Gingras

Featured Art: Three Dogs Fighting by Antonio Tempesta

They are big and smelly and mean,

and they’re living in her basement.

I think they are dogs, but they might be wolves.

Eight or eighteen of them, something like that.

They all would bite me if I gave them

the chance, so I’m really careful

when I herd them out into the yard.

What is it with my mother?

Most families just have pets—usually one dog

and a cat, nothing like this. How

did she let this happen to her?

She’s living in some decrepit house now on Rt. 9

in the next town over and she’s evidently lost

her taste in furniture. Everything is gold

with rickety legs. She and I watch

the dogs patrol around the yard

from behind a glass sliding door. My mother is angry

now that she’s old, and I think that maybe

she and the dogs deserve each other, but

I can tell that my mother is scared too,

and I want to help her out because

I’m the problem-solver in our family.

The dogs don’t play like normal dogs,

they just move around the yard

like big bullet-headed missiles. We have to get rid

of them somehow, I tell my mother who is

suddenly smaller than she was, and then I hold her

in my arms and she’s a little girl. Whatever you do,

don’t let them in, I whisper, but

she’s already dead of lung cancer.

Read More

Serenity Room

By Linda Hillringhouse

Featured Art: Buste van een oude vrouw by Anonymous

There are five recliners in a circle,

each with a spongy blanket.

The lights have been dimmed,

but an aide has left behind her walkie-talkie

and it sounds like it’s ready to lift off.

My mother is in one recliner, I’m in another,

an easy way to spend time now that she’s afraid

of the color red and distrusts windows

as if the glass weren’t there and the fingers

of the dwarf palmetto would reach in

and pull her down into its dark center

to cut out the last cluster of syllables

huddled beneath her tongue.

I look over to see if she’s sleeping

and her eyes are open as though

she’s forgotten to close them. Maybe

she’s on some dusky street where half-drawn

figures drift and sounds almost blossom

into meaning. Maybe she opens a door

and her aunts from Brooklyn are there

and clutch her to their mountainous breasts

where she could stay forever.

She tries to inch out of the recliner but an aide

intercedes with a cup of apple juice

which my mother examines closely

for poison and studies her hand as if it’s

screwed to her wrist. Then she brings the cup

to her lips as if it’s the last thing left

from the world when she was Shirley

and carried keys, lipstick, cash.

And I hope that the cold, sweet liquid

brings a moment’s pleasure, but how can it be

that it comes to this, that at the end you get

thrown in the ring for one more brutal round

without enough stamina to put on your shoes

or enough strength to say Thank you or Go to hell.

Read More

Catpants

By Richard Allen

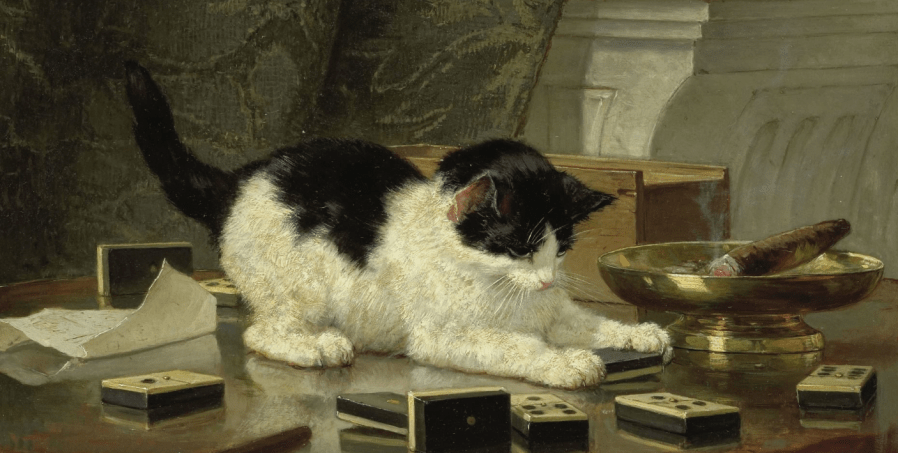

Featured Art: The cat at play, c.1860-1878 by Henriëtte Ronner

dead cat on the shoulder

my heart aches for a moment

until I realize it is only

a balled-up pair of sweatpants

why would I feel compassion

were it a cat lying dead there

and not a balled-up

pair of sweatpants

I think it is because

cats are defenseless

and innocent then

I re-evaluate

they are neither

the average housecat

has injured several people

in its short life

just for laughs

the person who had to throw

his sweatpants out the window

a moment’s thought for him

for his sweatpants

and for the sad conflict

that must have unfolded

between them

Read More

The Meat of It

By Michael Bazzett

To make a good book you need what William

Faulkner called “the raw meat on the floor.”

So before I started in I got some ground beef

and dropped it on the hardwood with a Spat!

It felt wrong. Like dropping a baby. But I did it

for art. When my son came home from school

he said, Why is there meat on the floor? I said,

Art. He nodded like maybe that made sense

and said, It’s kind of freaking me out. I know,

I said, me too. We all have to make sacrifices.

Is that blood leaking out or juice? he asked.

I’m not sure I’m one to make that distinction,

I said, mostly to avoid answering the question.

I didn’t tell him how strange it was to unwrap

the meat so carefully, the plastic peeling away

like a onesie on a warm day, and then just sort

of hurl it down at the hardwood with a Spat!

Are we still going to eat it? he asked after a bit.

I’m not sure, I said. I think it depends upon

a lot of different factors, a lot of ins and outs.

Is this a writing thing? he asked, because you

have that weird look in your eye. I’m your

father, I said. I held you as a baby. I’d never

use a moment like this just to make a poem.

Read More

Dune Cat

By Winnie Anderson

Featured Art: by Oliver Goldsmith

Eons ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch, the jaguar left his home and traveled across the cold arid grassland: his resolve set. The floods were coming again. If he stayed, the land would either be covered with water or be broken into land pockets, from which there’d be no escape. The time was now. He had to go.

In him the jaguar carried echoes of history, tens of millions of years’ worth of heat spikes, ice ages, tectonic upheavals, and mega-explosions. Time swirled uniquely around him. He felt two trajectories at once—like a stone cast into the deep lake of time, sinking down to the bottom where all life may have begun, as well as the outward rippling cat’s paw upon its surface. History. Present. Future. All there, his for the grappling.

Alone he headed south: crossing over what one day would be named the Bering land bridge. Well-suited to the task, weighing close to 400 pounds, the norm then, he ran through a dense mantle of cold and silence. In the morning light his rust-colored coat appeared red, broken only by dotted circular cave-black rosettes. The travel was hard, but the jaguar came into it, growing stronger as he went—proof he’d done the right thing by giving his instinct its due.

After months of traveling, and though he was not cold, his body began to shiver. Prescience told him change was imminent seconds before a rogue wind thrust the jaguar into a zigzag shudder of time, as if the stone sinking deep into the lake had jerked off course and suddenly crabbed sideways. Calling on everything he had by stirring up wells of power contained within him, the jaguar fought against this unknown force he could not fathom.

Read More

Now the Truth Can Be Told

By David Gullette

Featured Art: by Francis Augustus Lathrop

While I was assailed by a gaggle of captious sighs

you were somewhere else groping for lost teeth

or something or otherwise empty of solace, of course.

Or the time my edges all fell away taking

gritty treads and guy wires with them, where were you?

Breathing ethereal! Moonstruck!

Jesu! Did you think I couldn’t see you

slithering down the pike on your twenty axles,

the wind in your snoot, the coontail aflap flopping

in as crisp a tornado as any whip since

the blow that beveled Dubuque? Eh?

God knows you have failed me in need,

in time, in every intrusion of ice through my

window or down my back, every

whine of the plastic slug through my inner ear.

Do you think my patience is gold as glue,

sturdy as wings, marmot, asleep in your own aura?

Gelatinous posture! Asterisk! Aspic! Strip for your lashes!

Read More

Nobody Can Pronounce the Name of This Volcano

By Mike Wright

Featured Art: by Paweł Czerwiński

I was choosing a bag of almonds at the grocery

when a volcano erupted. These almonds

were an impulse buy, and now they commemorate

catastrophe. The volcano is elsewhere,

so I won’t experience cinders bruising the sky.

On another continent ash settles on buildings

and my snack is dusted in cocoa powder,

the packaging says semi-sweet. I’m realizing

this is the wrong flavor for a natural disaster.

Nobody can pronounce the name of this volcano.

I can’t speak its name and I want to know it,

to know destruction, the reality of molten

rock. Instead I’m standing around the store,

befuddled by almonds, by how to choose.

If enough pressure built under the surface,

I could be relieved of every decision.

Read More

A Friend Encourages Me to Travel to South America

By Mike Wright

Featured Art: by Bertha E. Jaques

I can’t handle cherries. When I see

them at the store, full of tart surprise,

I pass them up; it’s the breaking of tight

skin and release of flesh. I want

the thing ten steps down from the ecstatic.

Instead of cherries, cherry soda.

So how could I handle South America?

What would I do with a sea, with salt

air winding through me like a shell?

I live the nub of life, the thumbnail

sketch, fish sticks and cigarettes.

I would never survive the cherries

of South America. What’s a cherry

soda after a cherry? What do I dream of

after Brazil?

Read More

Nomenomancy

—divination by names

By Mark Wagenaar

Like each of us, it could only guess at its own begetting. A careless cigarette, electrical spark, Molotov cocktail hurled by an angry senior who had his letter to the editor rejected, we never found out how the fire started. Only smoke suddenly billowing above the town. Shreds of ten thousand newspapers upon the air, in slow drift through open windows, coming to rest on the eyelids & lips of men sleeping off the night shift at the furnace. Embers floated for hours through the streets, through back alleys, & ended up in the black fur of cats, gray hair of old men playing checkers, on the tongues of children who didn’t know better. A shroud upon the impatiens & petunias in tire & barrel gardens, on the feathers of pigeons in rooftop cages. In the silos the tatters found space amid the grains, & our news made it across the oceans: liquidation sales, stories on the alderman’s affair, the mayor’s new dog. And one death—one obituary. Larry, the boy who jumped his dirt bike into the canal. His name now upon the air, with our questions for him. We looked up at a sky that whirled with clouds of his name, & saw on that air once more the arc of his bike between the bridge and the rest of his life. His name rained down upon us, confetti for a parade of his absence. For years we found his name—in our underwear drawers, in our cereal boxes, in the big hair of our pageant contestants. In the open bags of sugar in the Home Ec classroom, the ones that girls would name and care for, & come to remember when their own babies were held up, his half-burned name against the brilliance of the sugar crystals, these sugar babies, each one named Larry.

Read More

Bodies That Drift in the River Flow

By Scott Gould

Featured Art: by Oscar Bluemner

Sometimes you know things before you know things. Mrs. Tisdale comes to the door, and I know something is wrong. I know. From the top bunk of my bed, I watch her coming up the sidewalk, walking fast but walking like a woman who is already lost, her skirt moving quickly around her, like a wave to anyone who spies through the window.

I know the doorbell won’t ring. She is not a bell person. She is too good a friend of my mother’s to announce herself that way. She knocks once and opens the door. What she doesn’t know is the bell doesn’t work anyway. It is shorted out somewhere along its line and my father has never pulled the wires and traced down them to find the problem. I hear Mrs. Tisdale’s voice flow up the staircase, so faint I can barely make it out, strained and pitched higher than normal. Her voice sounds like an animal she is trying to keep on a leash, trying to make it heel. Because her voice wants to run away from her. I hear my mother fall back on her nurse’s voice, that healing tone. I climb off the top bunk and move closer to the doorway.

“Now, Roberta, we shouldn’t jump to conclusions,” my mother says. “Let’s not worry until we have something to worry about.”

“Something’s gone wrong,” Mrs. Tisdale says. “I feel it.”

Men’s League as January

By Michael Pontacoloni

Featured Art: by Mark Landman

After we untie skate laces wound twice

around our ankles and knotted

like the ribbon of a plastic kitchen garbage bag,

and we pop our cold-socked feet from

stiff black Tacks and Grafs

like hard pits from leathery dates,

all the blood worked up in thighs

screws down our shins and

floods our numb feet new again.

We laugh through clenched teeth at the charge

and fuzz of it, our toes

swelling round to halogen bulbs and

buzzing with a filament of joyful pain,

that brittle wire.

Burning cold they

might shatter so in old gray sneakers we

hobble to the parking lot,

at the open trunk of Ryan’s gray Corolla wobble

under sweaty hats and clouds of breath

and dispute the long-gone referees

with Narragansett cans till midnight.

We cough. We kick a snowbank.

Our neck hairs

icen to filigrees. Geno

glows in a T-shirt. What bright glass,

this golden crescent of beer in a can rim

yearning to freeze.

Read More