Anti-Confessional

By Catherine Stearns

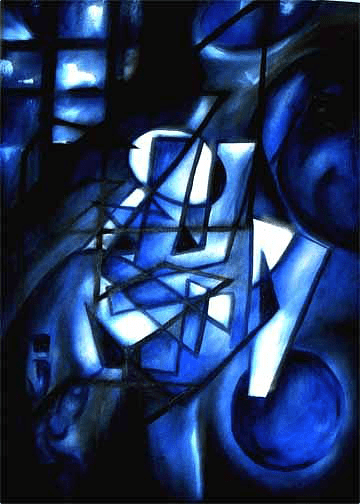

Featured Art: Girl in a Blue Dress, c. 1891 by Philip Wilson Steer

In one photo, she’s wearing a sapphire blue dress,

a black cloche posed rakishly over one eye,

a corsage of pink rosebuds around her wrist.

On the back it says JB & RPS, the man

in shadow next to her. This was before the war,

before they reinstated the marriage bar

and she lost her job when she married my father.

One hot summer night, maybe five years after he died—

we’d stripped down to our underwear to play Scrabble—

I asked her about grad school and her fifth-floor walk-up

with Mary Maud, about eating oysters at the Grand Central

Oyster House every Sunday, and the gold lighter engraved

in the Tiffany font at the back of her jewelry box, and I asked her

if she’d ever slept with anyone besides my dad.

She took an extra long sip of her G&T and told me to

mind my own business. Then reached over

to put her X on a Triple Word.

Read More