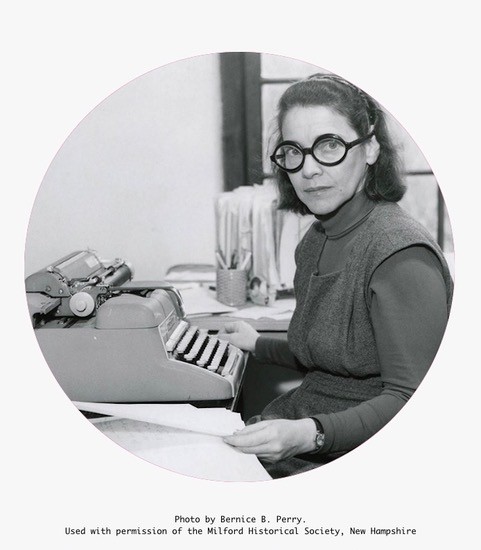

Essay: The Journey and Return of Elizabeth Fisher

By Elle Therese Napolitano

In Elizabeth Fisher’s 1970 story, “A Wall Around Her,” published in Aphra (Volume 4, Number 4), the main character pounds on the locked door of a house where she’s rented a room. As she waits for someone to respond, she is overcome by crushing loneliness and futility. “I never was in, never was and never will be, always outside, always trying to get in, beating with my fists, pleading, ‘Let me in. Let me in.’ Why don’t I just give up the struggle, stop trying to reach people, to be a human being.”

Elizabeth Fisher was a writer, editor, translator, publisher, teacher and feminist, but these days, she is best known—and unknown, it turns out—for sparking Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1986 essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” republished after Le Guin’s death as a tiny book (Ignota, 2019). It’s safe to say that now, thousands of people have seen her name in print—Le Guin names her right there in her resurging essay, along with a partial title of Fisher’s book, Woman’s Creation (though the publication date is wrong)—in which she puts forth “The Carrier Bag Theory of Evolution.” Since Le Guin’s essay was reprinted, new writings about her essay have proliferated. Nearly all mention Fisher. But people don’t seem to know anything about her. There’s all this stuff out there about carrier bags and Ursula Le Guin, but what about Elizabeth Fisher? What about her life?

Read More