By Angie Estes

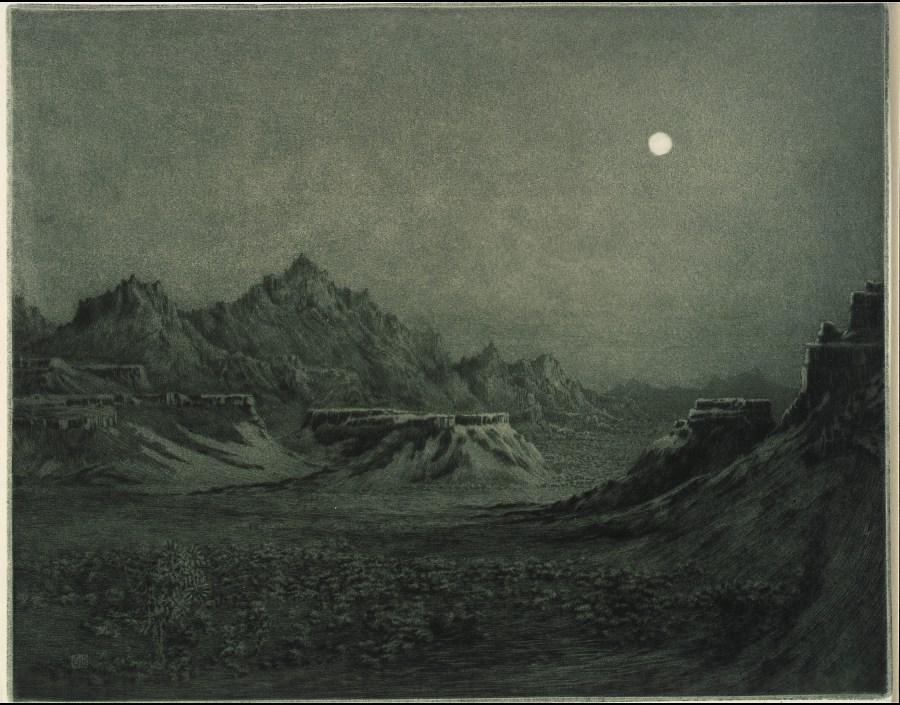

Featured Image: Arizona Night by George Elbert Burr 1920+

when starlings swell over Otmoor, east of Oxford, as the afternoon

light starts to fade. Fifty flocks of fifteen to twenty starlings, riffraff

who have spent the day foraging in fields and gardens suddenly rise

like a blanket tossed into the sky, a revelling that molts sorrows to roost

rows, roost rows to sorrows as they soar through aerial corridors and swerve

into the shape of a cowl that lengthens to a woolen scarf wrapping

and wrapping, nothing at the center but throat: thousands of single black notes

surge into a memory called melody, the lovers damned but driven on

by violent winds in the cold season when starlings’ wings bear them

|along in broad and crowded ranks, extended cadenzas to pieces that

never get played, brochure for the flared tip that begins with the tongue

and lips of the embouchure wrapping the saxophone’s slurred

howl, scrawled signature of the sky. Thousands fly but never collide

in their pre-roost ritual, Dante’s long list of God’s works excited

raked left and right over leafless branches of trees until they

drop like the bodies of suicides, draped on thorns of the wild

thickets their cast-off souls become, unable to rise the way a wave

nearing shore will crest, something on the tip of its tongue

thrown back before it breaks and splays, starlings laid down

like the wave’s rain of sand or words falling

out of a sentence: art slings, we called them, grass lint, snarl gist, gnarls

sit. Art slings them this way, last grins, art slings swell, rove

over, red rover, red rover, send artlings right over, artlings

rove, moor to swell, write Otmoor all over

Read More