For My Mother, Who Detested Sports All Her Life but Became in Her Final Years the University of Minnesota Men’s Basketball Team’s Most Devoted Fan

By David Thoreen

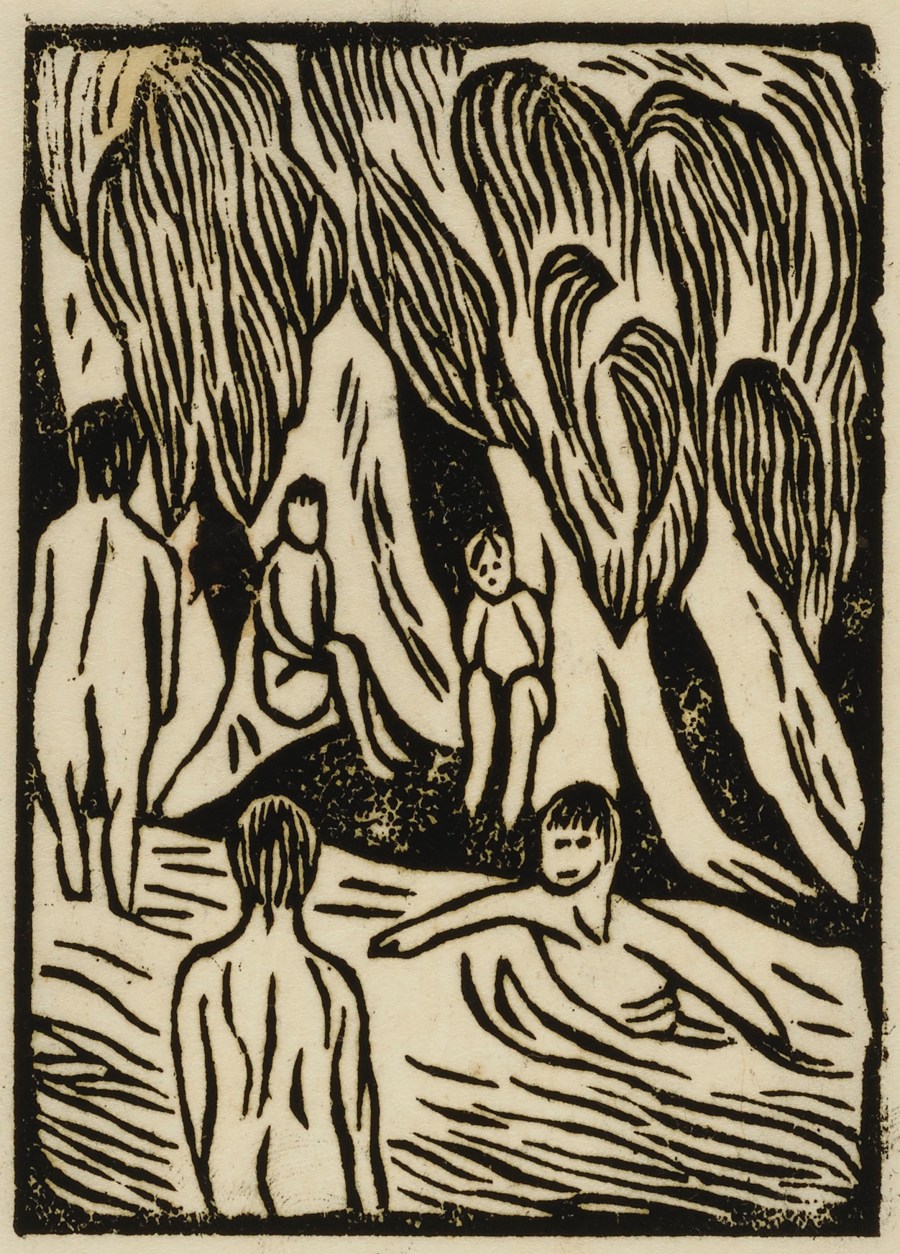

Featured Art: “Field Within a Field” by Thad DeVassie

For her, by then, the news was nonsense, names

she did not know, public policy proposals she

could not follow. Ugh, the weather girl, she’d say,

before she stopped talking altogether. What

are windows for? She still sat with a book in her lap

but rarely opened it. Why basketball, I wondered,

until I watched her watch a game. There was no plot,

no morally murky postwar setting, no confusing

characters, no Monsieur Poirot, no Miss Brodie,

no exposition, no dialogue filled with subtext

and subterfuge, no metaphors or motifs. No past

and no future, only this: ten men running full tilt

coast to coast, one catching a pass and spinning

at the top of the key, stuttering, feinting right,

then driving and in three quick steps rising and floating

to the rim, a flick of his fingers releasing the ball

that spins just so against the backboard and drops

through the hoop, riffling the net.

She couldn’t remember her husband or grown children,

but when the Golden Gophers scored and the screen filled

with close-ups of anonymous fans draped maroon

and gold, pumping fists, blowing kisses, waving their beer,

she knew it was her turn to cheer.

Read More