by Melissa Cistaro

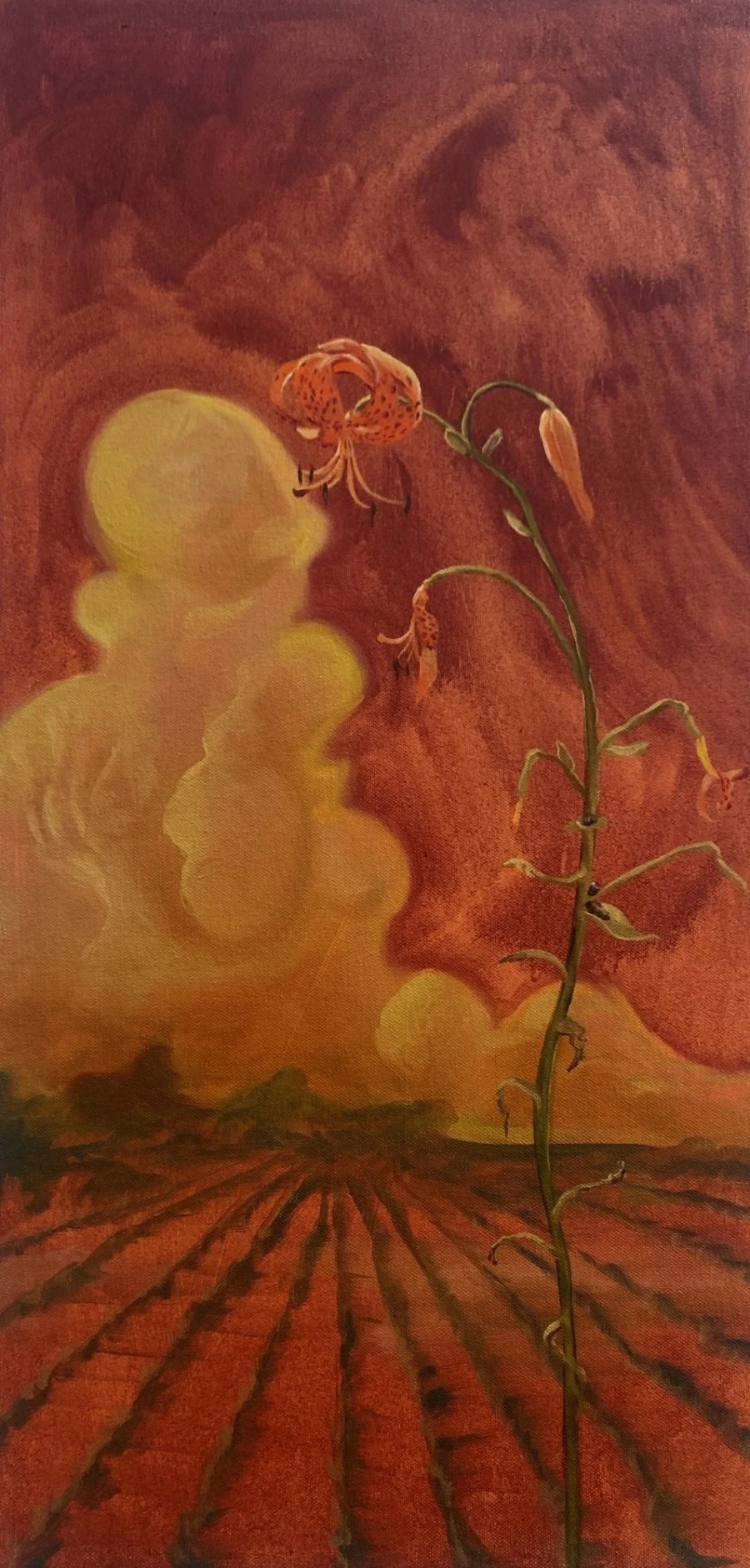

Featured art: A Farm in Brittany by Paul Gauguin

1975

My mom pours the warmed milk from the stove into oversize plastic bottles, then pops on the giant caramel-colored nipples.

“Do you want to feed one of the little ones down in the calf barn?” she asks.

I cannot contain my smile. My Keds are on in three seconds.

I follow her down the grassy path, holding the warm milk bottles against my chest and trying to copy the sway of her hips. She explains how the calf barn is the holding place for the young Holstein calves who are being weaned from their mothers’ milk.

“Roger likes to wean them young,” she tells me, “so that the mother cows can get back to their job of being milk cows.”

The calves cry and bleat like goats when they see us with the milk bottles. A black-and-white calf shoves his head through the wood slats of the stall and stares up at me with his big polished eyes. I put the rubbery nipple close to his mouth. He grabs and tugs fiercely at the bottle.

“Hold on tight,” my mom says. “That guy is a tough little sucker.”

My calf slurps as he drinks, then yanks at the nipple like he’s mad at it. Milk splatters across his soft black face. When he’s done with the milk he wants to keep chewing and sucking on the rubber tip, but my mom says that will put too much air in his stomach.

“Just stick two fingers in his mouth,” she tells me from across the aisle.

“What?” I say.

She walks over to my calf and sticks her middle and pointer finger right into his mouth. He latches on and starts making sucking sounds.

“There are no teeth in there, just gums,” she says.

I hesitate. I am not certain about this. She grabs my hand and pulls it toward the calf’s mouth. He latches onto my two fingers with such force that I am startled. His mouth is strong and smooth inside. I feel his tongue, like fine sandpaper polishing my fingers. I start to laugh. My mom laughs. I don’t want this to stop. I want to learn as much as I can about living on a farm in case I ever get to live on one. I take my other hand and rub the calf’s face, swirls of

thick black velvet, a perfect white diamond on his forehead.

My mom says she’s got a few chores to do back up at the house, and I ask if I can stay here in the calf barn for a while.

“I like it here,” I tell her.

“I’m glad,” she says. She smiles at me, pushes an unlit cigarette into her mouth and gathers up the empty milk bottles.

My fingers get a little sore from staying in the calf’s mouth so I pull them out. The calf seems okay because after a minute he buckles down on his wobbly legs and flops onto the straw floor. I decide to do a little exploring around the barn. There are dusty bird’s nests tucked all around the rafters and small birds like starlings that swoop down to gather bits of straw from the ground. I find a place to sit in the feed room where there are burlap sacks filled with

cracked corn and molasses-covered oats. I push my hands deep into the open sacks and pull the molasses oats close to my nose. It smells good enough to eat.

I take a walk to the far end of the barn aisle where the calf stalls are empty. There are two tall white buckets with lids on them, the plastic kind that painters use. They look out of place to me for some reason, like maybe they were set down there and forgotten. I pry the lid off the bucket closest to me. There is no particular smell.

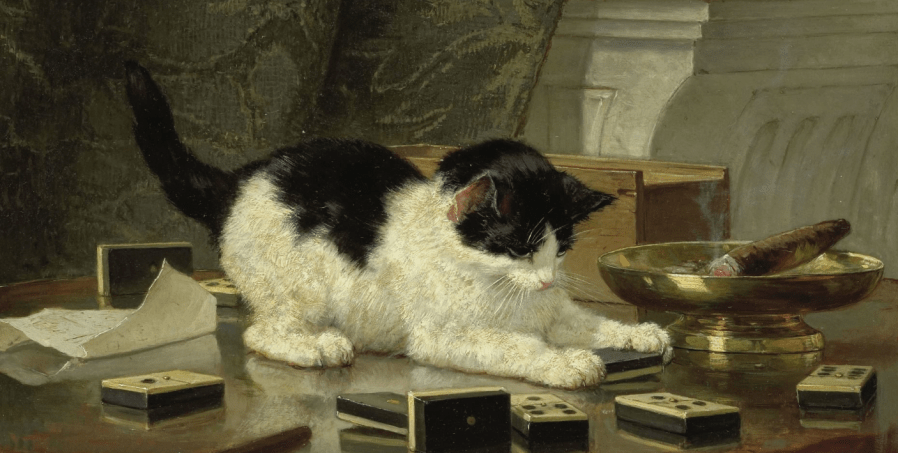

I am not sure if what I am seeing is right or true. Kittens. Piled up to the brim. Clean white fur. Brown, black, tan, orange. Small paws with fleshy pads as soft as apricot skin. Wiry tails. Tiny pink noses. Whiskers, as fine as fishing line, almost transparent.

It is not a dream. I push the lid back on. I think there must be more than a dozen piled up in there. I pry open the other bucket only because I want it to be something different. But it’s not. One all black, one striped orange, one smoky gray, more colors underneath. Soft triangle ears, thin as potato chips. I want to stop staring but I can’t. A small calico kitten lies across the top of the heap. Its eyes are closed, but the shallow part of its belly moves—barely, up and down like it’s in a deep sleep. I want to touch it, but I am afraid. I don’t know what to do. I put the lid back on.

I walk back up the hill toward the farmhouse, my heart pounding underneath my yellow T-shirt, the tall wet grass soaking the bottoms of my jeans. When I open the screen door, I see my mom at the table with her New York Times crossword puzzle, her coffee and a cigarette. She’s smart with words. I’m not. I’ve got a throat full of gravel that usually keeps me from saying what I want to say.

But I know what my question is.

“Why are all those kittens in the white buckets?”

She keeps looking down at her crossword puzzle like she’s just about to figure something out. Her dark bangs hang like a frayed curtain across her forehead. For twenty seconds, I don’t even think she’s going to answer my question.

“Oh, that,” she says with a frown. “You weren’t supposed to see that.

Roger was supposed to dump them.”

I wait for her to say something more.

“I’m sorry you had to see that, darlin’. It’s the way of the farm here.”

She smashes the clump of soft ashes down with the filter of her cigarette. There is sparkly pink polish on her fingernails. I hate it when she’s so matter-of-fact.

“There were just too many kittens.”

“What do you mean too many?” I ask.

“Those were feral kittens, wild and inbred—just the ugly ones. Believe me. I can tell the inbred ones right away, their eyes are wide-set and slightly askew. Their heads are oversized.”

“But how did they die?”

My mom gets up from the table with her ceramic coffee cup, and goes into the kitchen. I can tell she doesn’t want to listen to my questions.

“Chloroform is what Roger said to use.”

She measures out a heaping spoonful of sugar into her cup.

“But power steering fluid works just as well. It’s very quick. They don’t suffer.”

I feel my throat tighten up like a fist. My legs are as wobbly and uncertain as the calves down in the barn.

“Mom, I saw one breathing on the top, a calico one, not an ugly one, but a long-haired calico.”

“There were no calicos,” she says, slamming the garbage can lid down. “And, you did not see any kittens breathing.”

“I did, Mom. I definitely saw that one on top.”

“None of those kittens were breathing, you understand?”

I am strangely afraid of her. She knows how much I love kittens. I try to stop the image of her hands pushing those kittens into the white buckets. I know there was a calico. I know that she killed them.

She heads out the screen door, says she’s got to grab a few fresh eggs and she’ll be right back.

I watch her outside the window, walking through the tall grass. I recall what I once overheard her say—that she thought about drugging my brothers and me when we were small because she didn’t want us to suffer. She had an emergency plan in case there was an awful natural disaster. She would give us all sleeping pills. We wouldn’t suffer. But I am almost ten now. I am too big to trick like that.

I wait at the window for her to come back. I wait because I want to feed the calves with her again. I wait because I want to swirl the sugar and cream into her coffee and breathe in her L’Air du Temps perfume. I don’t know when the next time I’ll see her will be. I scratch my fingernail along the thin white paint that covers the window sill. I remind myself that there are things I am not supposed to talk about or remember. I am not supposed to remember the day she drove away in her baby-blue Dodge Dart. Everyone tells me that I was too young to remember. But I remember everything. “Too many,” she said. I know this phrase. I heard her screaming it late one night before she left my brothers and me.

I reach into my jean pockets and I push the secrets in as far as they will go. Between my fingers I roll around a soft piece of gray lint. I don’t want anyone to know that my mom killed those kittens. I push my hands into my pockets even deeper. I make room for the kittens, because they are a new secret.

Originally appeared in NOR 7