When I Played You “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”

By John Jay Speredakos

And all that remains is the faces and the names

of the wives and the sons and the daughters

—Gordon Lightfoot, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”

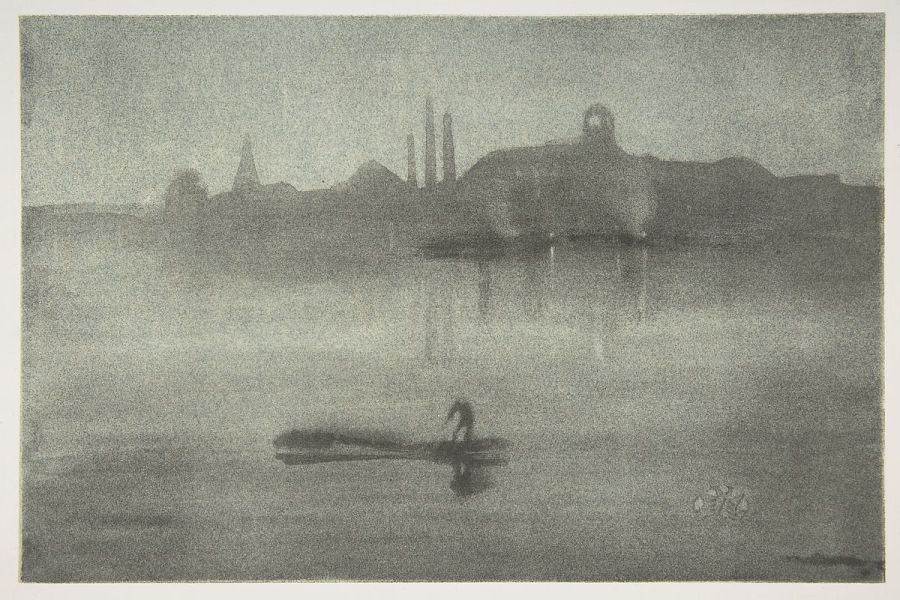

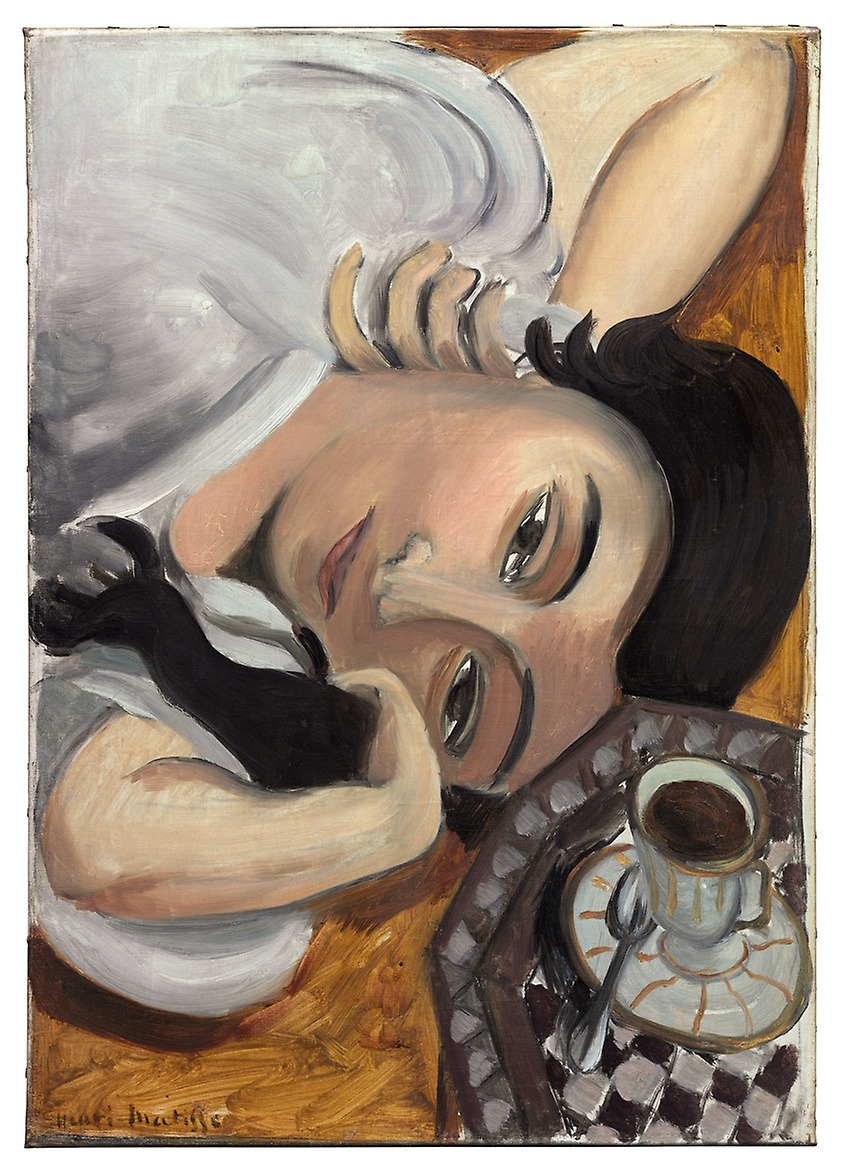

As we drove through Wyoming and

your eyes closed just a bit while

the sunlight slanted through the moonroof,

or maybe it was moonlight through the sunroof,

and it could have been Montana,

and you wondered if Gordon Lightfoot was an actual Indian.

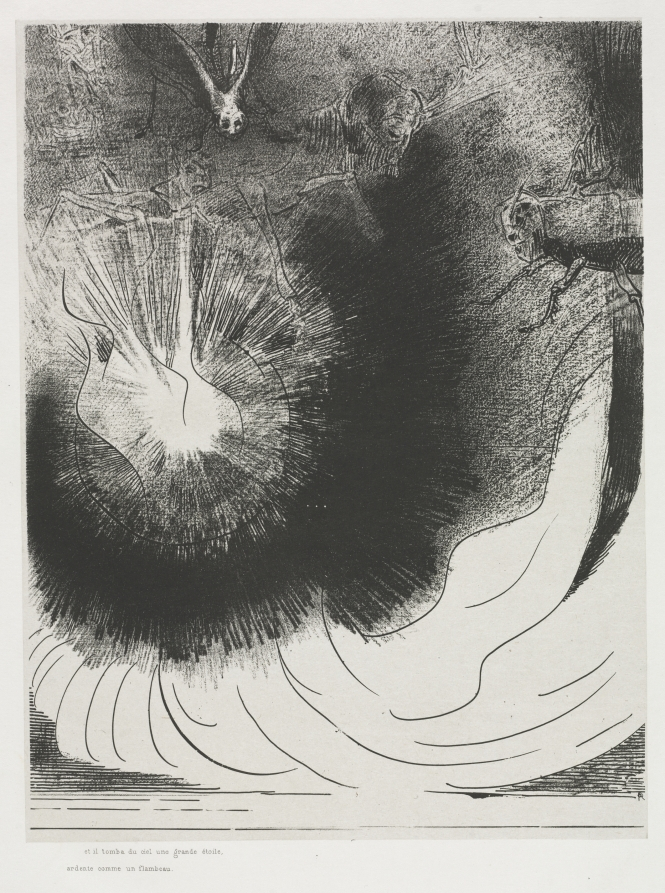

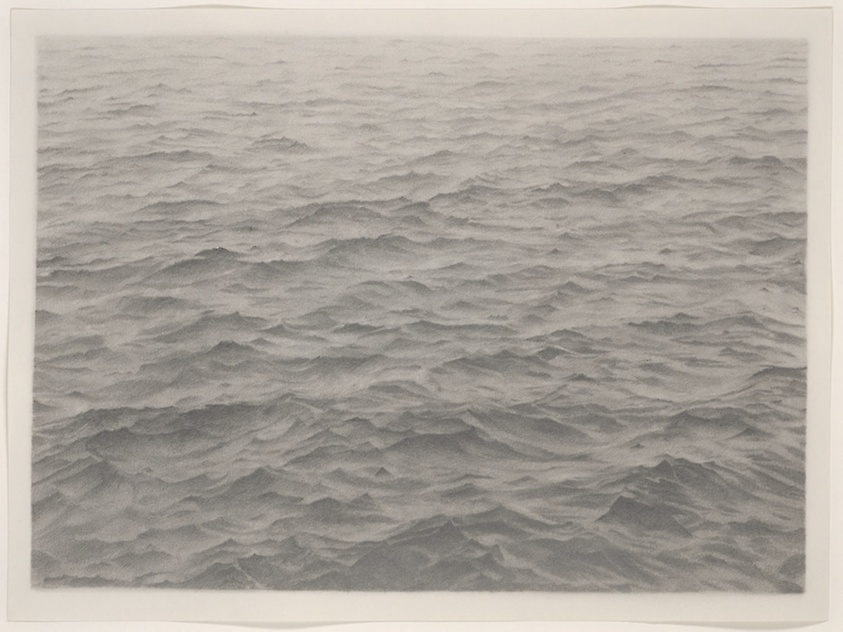

You didn’t know that a Great Lake was really an ocean

with a chip on its shoulder, and an ore freighter

could be a coffin in certain Novembers.

Daughters can be like that: full of speculation that makes you doubt

what you already know. But I know this—

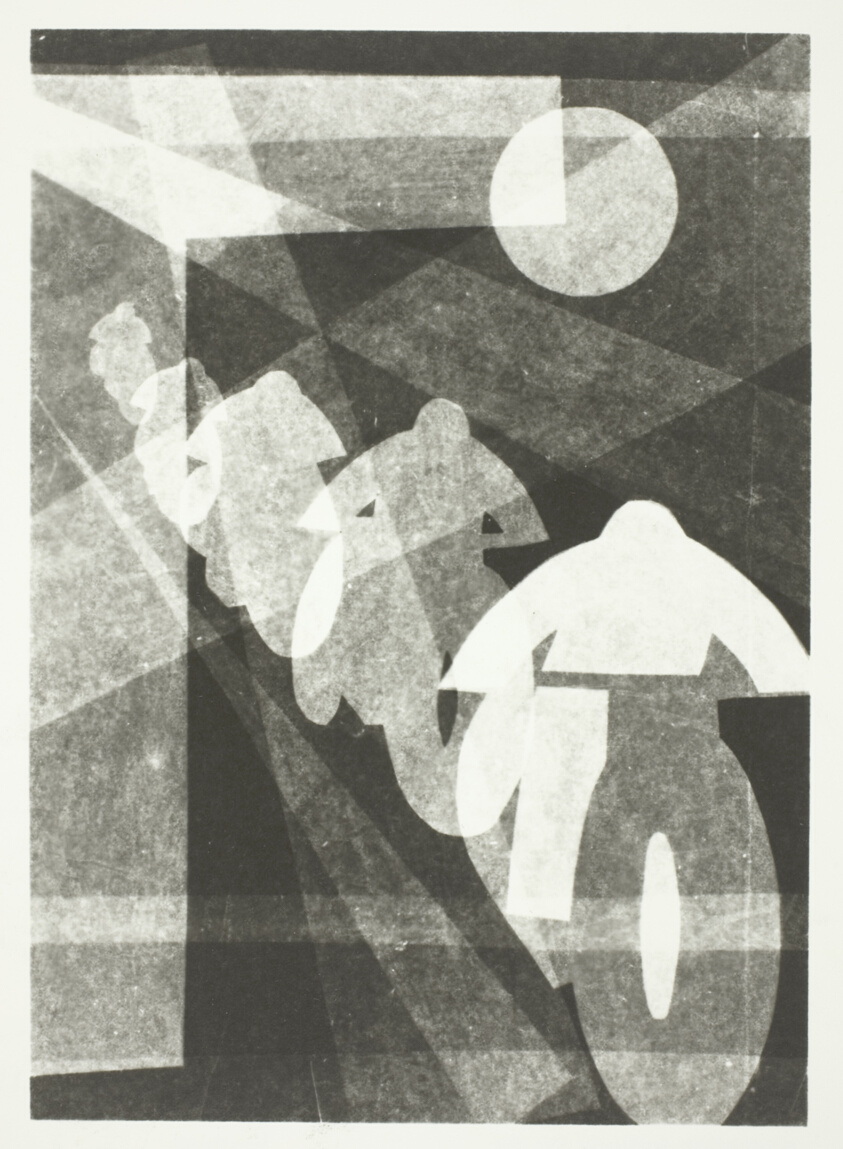

your hand drummed on your thigh and your head nodded in time and

for a few moments those sailors were back on deck

breathing sweet oxygen, instead of Lake Superior.

Such is the power of a tune to restore the dead.

And your eyes blinked, and a week went by, your hand waved

and a month disappeared; you bobbed your head for a year or so.

And when the song ended, you were a young woman

about to sail away yourself.

And I thought of the depth of loss and how it’s relative,

some can never come home, some can never go home

again. Why do stories of drowned sailors always cut so deep?

Something about the going away and the not coming back.

The not being here, but not elsewhere either.

I don’t know the particulars, but I do know the future—

how the freighter will founder, the sunshine diminish

in a howl of seething froth. And me still poised on the pier,

eyes on the horizon. When the church bell chimes

those twenty-nine times, I’ll mourn it all, all the sailors,

all the daughters, all the souls that won’t come back.

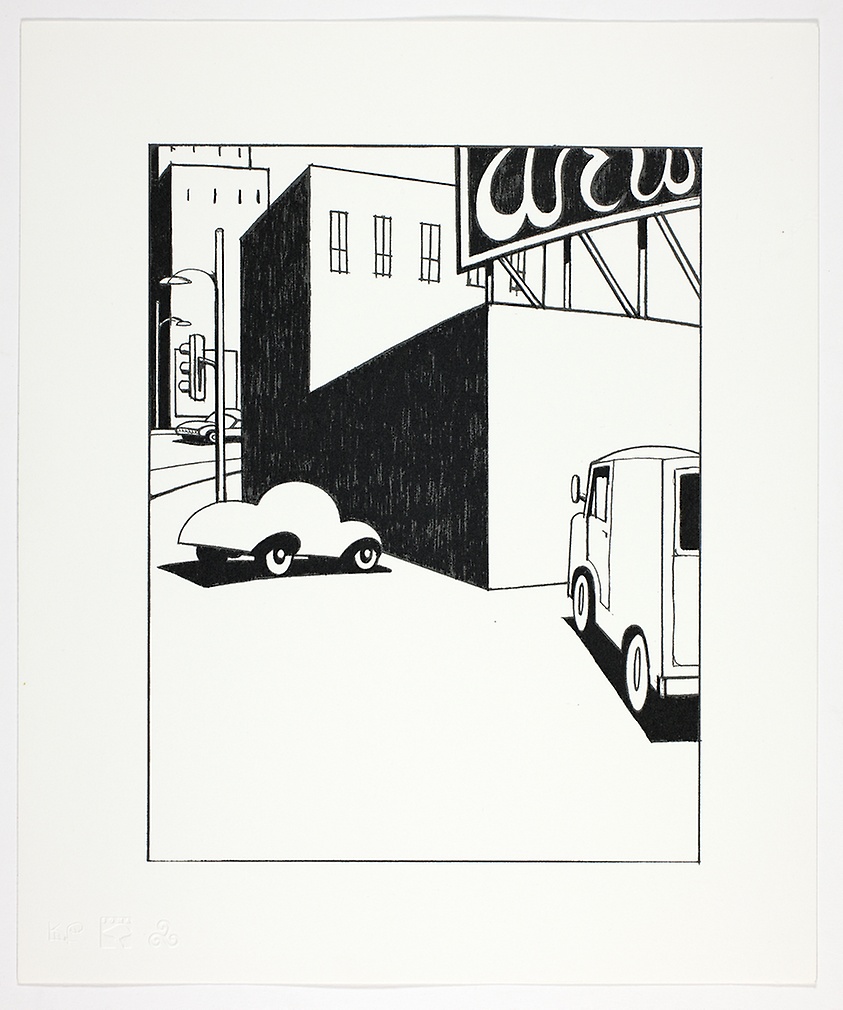

But for now, in Colorado I think it was,

we drifted in our little ore ship,

bobbing on the only sea that mattered,

ignoring the storms that always gather,

always smother and smite and threaten

the future, but never the now.

Like a vessel on the swelling waves—

some come back, some don’t

even know they’ve left.

Read More