Like a Struck Tuning Fork: On Translating Sound in Tranströmer’s “The Station”

By Patty Crane

Featured Art: Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare by Claude Monet

The Station

A train has rolled in. Car after car stands here,

but no doors are opening, no one’s getting off or on.

Are there any doors at all? Inside, it’s teeming

with closed-in people milling back and forth.

They’re staring out through the unyielding windows.

And outside, a man walks along the train with a maul.

He’s hitting the wheels, a faint ringing. Except right here! 7

Here the sound swells unbelievably: a lightningstroke, 8

a cathedral bell tolling, a round-the-world sound 9

that lifts the whole train and the region’s wet stones. 10

Everything’s singing! You’ll remember this. Travel on!

In Tomas Tranströmer’s poem, “The Station,” from his ninth poetry collection, The Wild Market Square (1983), the ordinary scene of a train at the platform becomes a metaphor for something far from ordinary. The sound of the struck wheel widens beyond this singular everyday experience to contain the great mystery that surrounds our existence, a mysteriousness that, for a brief instant, feels as accessible as it does out of reach. This brings to mind Robert Bly’s often-cited remark about Tranströmer’s poems being “mysterious because the images have travelled a long way to get there.” “They are a sort of railway station,” he says. And quite literally so in “The Station,” where images arrive from vastly different points of origin and briefly stand together in the same place.

Read More

On Translating Choctaw Poems

By Marcia Haag

Featured Art: Sunset on the Sea by John Frederick Kensett

The challenges of translating from one language to another are well discussed and lamented. These challenges increase when poetry is involved: not only must the meaning emerge, but the product must sound like something that could count as a poem. When working in a native American language, these problems are, frankly, insuperable, but we are not thereby let off the hook. I am a linguist and scholar of the Choctaw language who comes to translation indirectly.

It is not clear that native Americans composed much poetry. (How would we know? What’s the difference between a war chant and a poem?) One group that, to my reckoning, clearly composed lyrical poetry was the Uto-Aztecans. The southern tribes, the Mixteca, had writing, after all, and we have a bit of the stupendous lyrical literature that was left unburned when the Spanish chose to rid humanity of indigenous cultural artifacts.

Read More

Sense and Serendipity: The Masochistic Art of Translating Surrealism

By Mark Polizzotti

Featured Art: Flower Clouds by Odilon Redon

Surrealism was an art of serendipity. Its aesthetic and philosophy revolve around such elements as surprise, chance, marvel, and what the French call la trouvaille, the discovery, the treasure happened upon. André Breton argued repeatedly that the point of automatic writing—Surrealism’s first and most celebrated tool— was to provide Surrealism not with an exciting new literary technique but with a method of research, a doorway into unexploited mental processes that were within everyone’s reach. As he rather cheekily put it in the first Manifesto, “Language has been given to man so that he may make Surrealist use of it.”

The thing about serendipity, of course, is that it implies a fair amount of spontaneity and blind luck. You can’t plan chance occurrences. It’s one thing if you’re sitting at your favorite café table, paper at the ready and pen poised to take flight. It’s quite another if you’re trying to recreate, in another language, someone else’s experience of that flight, and this is where translation and automatic writing begin speaking at cross-purposes. The trick here, in other words, is that we’re dealing with a text composed (supposedly, at least) in a trance-like flow, in which one word or phrase begets the next, begets the next. The first challenge is to make the translation sound as if it was composed in the same way, but there’s more to it than that: there’s also a psychological element. The mental process that might generate a flux of words in French is rarely the same as the process in English.

Read More

Finding the Just Name: On Translating Ismailov

By Robert Chandler

Featured Art: The Sea by Gustave Courbet

One of the most difficult works I have translated from Russian is Hamid Ismailov’s The Railway. This novel has a huge geographical sweep, taking in not only most of Soviet Central Asia, but also Iran, Afghanistan and parts of European Russia and western Europe. It incorporates a great deal of twentieth-century political and cultural history. It comprises many separate stories, often linked together only tangentially. It is full of unfamiliar real-life detail—Soviet, Muslim, and (most bewilderingly of all) Muslim-with-a-Soviet-veneer-to-make-it-acceptable-to-the-authorities. And there are at least 137 different characters. How could I make all this not only comprehensible to people from another world but also interesting and enjoyable for them? One approach would be to simplify. The publishers of the French translation omitted about half the chapters, leaving out everything that did not relate to the story of the novel’s central family. I have no doubt that this stripped-down version has its merits, but this is not the way I wanted to go myself. The Railway is exuberant and Rabelaisian, full of slogans, spells and curses; Hamid (the author and I are close friends, so I shall refer to him by his first name) is deeply aware of the power of fantasy, of the way words beget words and stories beget stories, of the power of language to create reality. I did not want to sacrifice this exuberance.

Read More

On Translating Thai Artist Wisut Ponnimit from Japanese to English

By Matthew Chozick

Featured Art: Head of a Woman with Bent Head by André Derain

Tuk-tuks, manga as literature, onomatopoeia, Valentine’s Day

My wife and I climb with light luggage into the back of a three-wheeled Thai taxi, a tuk-tuk. As we drive off, city lights and a pink sunset blend marvelously together. Our tuk-tuk weaves through traffic as I see a gold adorned Buddhist pavilion, a Burmese-Mexican burrito restaurant, and then a Yamaha motorcycle dealership. It is, incidentally, from the land of Yamaha that we have just arrived by airplane.

Far away from our home in Tokyo, I’ll spend the week finishing an English translation for Wisut Ponnimit, Japan’s celebrated Thai author and illustrator. Wisut, who learned Japanese as an adult and now writes in the language, happens to be holding a joint art exhibition in Bangkok with Tokyo-based photographer Kotori Kawashima. Before attending the gallery show and conferencing with Wisut, there are a few difficulties to resolve with translating his manga book, Him Her That.

Read More

The Stones and the Earth: On translating Wiesław Myśliwski’s Stone Upon Stone

By Bill Johnston

Featured Art: Alpine Scene by Gustave Doré

Wiesław Myśliwski’s magisterial 1984 novel of Polish village life Stone Upon Stone (Kamień na kamieniu) is a text in which language plays a central role. The entire novel reads like a magnificent sustained spoken monologue; Myśliwski’s gift for conveying the pithy, unsentimental wisdom of peasant language is apparent in every sentence, and it is language, not story, that ultimately drives the narrative and makes the book the masterpiece it is.

In the more than five-hundred pages of this astounding book, no word is more central than ziemia. Yet at the same time, no word is more untranslatable into English—despite the fact that ziemia is a seemingly ordinary, everyday word. The problem is that ziemia, unremarkable as it is, occupies the semantic space of several equally ordinary, overlapping notions in English. Foremost among these English meanings are: earth, in meanings such as that of one of the four classical elements, contrasted with air, water, and fire (it is, for example, the name of our planet in Polish); land, as in something one can farm, and that is measured in acres—it also appears in Polish in phrases such as “homeland” and “promised land,” and in this meaning is used in a phrase like “on land” to contrast with “on the sea”; ground, for instance in a phrase such as “lying on the ground” or “the ground under one’s feet”; and soil, the actual material in which one grows things.

Read More

On Translating C.P. Cavafy’s “Come, O King of the Lacedaimonians”

By George Economou

Featured Art: Green and Blue: The Dancer by James McNeill Whistler

Άγε, ω βασιλεύ Λακεδαιμονίων

Δεν καταδέχονταν η Κρατησίκλεια

ο κόσμος να την δει να κλαίει και να θρηνεί·

και μεγαλοπρεπής εβάδιζε και σιωπηλή.

Τίποτε δεν απόδειχνε η ατάραχη μορφή της

απ’ τον καϋμό και τα τυράννια της.

Μα όσο και νάναι μια στιγμή δεν βάσταξε·

και πριν στο άθλιο πλοίο μπει να πάει στην Aλεξάνδρεια,

πήρε τον υιό της στον ναό του Ποσειδώνος,

και μόνοι σαν βρεθήκαν τον αγκάλιασε

και τον ασπάζονταν, «διαλγούντα», λέγει

ο Πλούταρχος, «και συντεταραγμένον».

Όμως ο δυνατός της χαρακτήρ επάσχισε·

και συνελθούσα η θαυμασία γυναίκα

είπε στον Κλεομένη «Άγε, ω βασιλεύ

Λακεδαιμονίων, όπως, επάν έξω

γενώμεθα, μηδείς ίδη δακρύοντας

ημάς μηδέ ανάξιόν τι της Σπάρτης

ποιούντας. Τούτο γαρ εφ’ ημίν μόνον·

αι τύχαι δε, όπως αν ο δαίμων διδώ, πάρεισι.»

Και μες στο πλοίο μπήκε, πηαίνοντας προς το «διδώ».

Come, O King of the Lacedaimonians

Cratisicleia did not deign to allow

the people to see her weeping and grieving;

she walked in stately silence.

Her serene demeanor revealed

nothing of her sorrow and her torments.

But even so, for a moment she couldn’t contain herself;

and before she boarded the hateful ship for Alexandria,

she took her son to Poseidon’s temple,

and when they were alone she embraced him

and kissed him, who was “suffering grievous pain,” says

Plutarch, “in a state of conturbation.”

But her strong character fought back;

and regaining her self-composure, the magnificent woman

said to Cleomenes, “Come, O King of the

Lacedaimonians, when we come out

of here, let no one see us weeping

or acting in any way unworthy

of Sparta. For this alone is in our power;

our fortune will be only what the god might give.”

And she boarded the ship, heading for that “might give.”

Read More

The Homophonic Imagination: On Translating Modern Greek Poetry

By Karen Van Dyck

Featured art: Two Pupils in Greek Dress by Thomas Eakins

When I translated Jenny Mastoraki’s prose poem “The Unfortunate Brides” (1983) I drew on the beat and even the syllabic count of the Greek to create a rhythm that was legible, but new in English:

. . . the way a roóster lights up Hádes, or a gílded jaw the speéchless night,

a beást jángling on the rún, and the ríder búbbles up góld.

For Anglophone readers, the four phrases make up a recognizable stanza, though somewhat unusual with two long beats in the first two phrases and three shorter, faster ones in the last two. Newness arose not simply from the surreal imagery, but from the sound on which it rode.

To focus on the sound of the source text is to run counter to the dominant translation strategy, which focuses on meaning. This is true more generally, but also in the case of Modern Greek poetry. Translations such as those by Edmund Keeley and Phillip Sherrard introduced the poetry of C. P. Cavafy, George Sef-eris, Odysseas Elytes and Yannis Ritsos in an idiom that reads easily in English and makes the living tradition of myth and history readily available to an Anglophone audience.

Read MoreNew Ohio Review Issue 13 (Originally printed Spring 2013)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

Issue 13 compiled by Will Bower.

Not Ready for Our Close-Up

By Elton Glaser

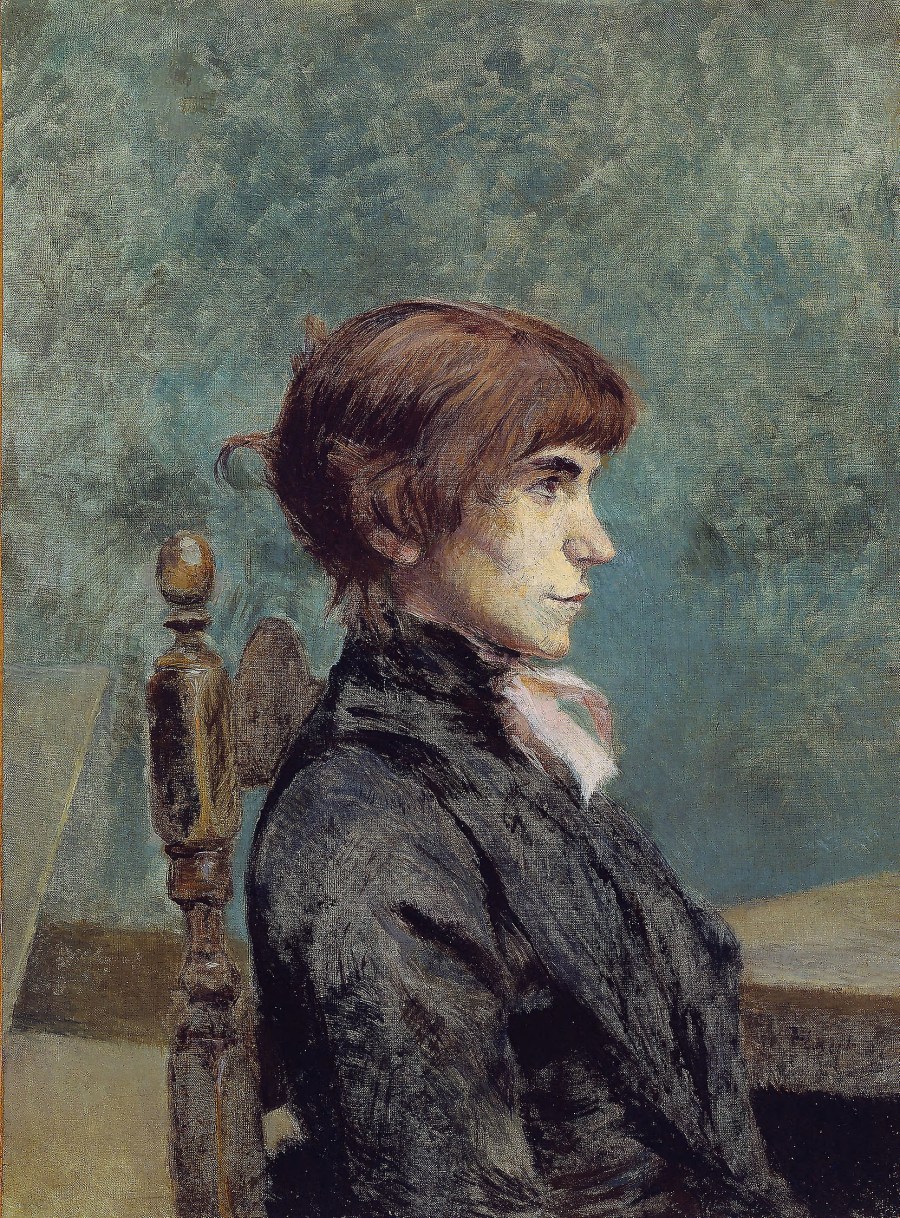

Featured Art: Portrait of Jeanne Wenz by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

So here we are, helpless among the infinities,

Like noonday devils with the midnight blues.

It’s no use looking for clues in the cradle or the cave.

They’re having none of it down at the U, the cranky professors

And the poets won’t tuck us in with milk and macaroons,

With the sleepy rise and fall of blanket verse.

The mind makes its way among the mazes, inconsolable, quick,

The cross-eyed love child of amnesia fucked by adrenaline.

We might as well steal some Etruscan tear jars for the soulwater.

We might as well scrape a pig’s ear to flavor the beans.

It’s going to be a long night of gossip among the isolatoes,

Candles writhing their light against the slippery walls.

Read More

Namaste

By George Bilgere

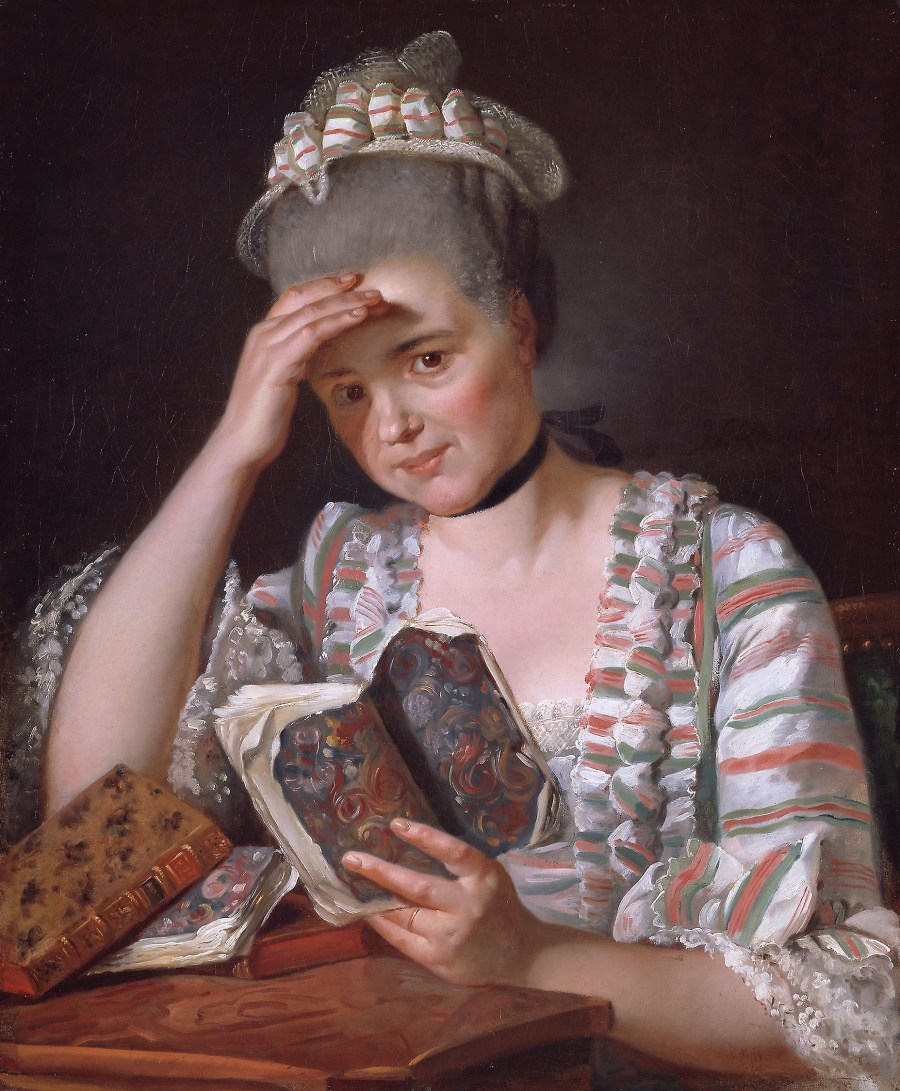

Featured Art: Madame François Buron by Jacques-Louis David

The slender, balding fellow

walking out of the yoga center

with his neatly rolled up yoga mat

and seraphic, post-yoga glow

probably thinks he is superior to me

as I clump down the sidewalk with my poor posture

and relatively limited spinal flexibility, my failure

to think deeply, if at all, about my breathing.

Which is fine. He’s entitled to his opinion.

However, what he doesn’t realize

is that I live on the same street as he does

and I happen to know, from walking past his house

on garbage day, that he makes no effort whatsoever

to recycle. Newspapers, bottles, plastic containers—

the things you’re supposed to put in the blue bag—

he just sticks in the white bag, along with the coffee grounds

and cantaloupe halves and the rest of the so-called “wet” trash.

Even beer cans are in there (a cheap, off-brand beer, I might add).

I guess saving the planet isn’t that important to him,

compared with mastering Down Dog or Up Dog or whatever.

So here he is feeling superior to me,

whereas in fact I am the more evolved being,

and I give him a glance of cool, skeptical appraisal

which I hope conveys this.

Read More

Snorkeling

By Allison Funk

Featured Art: Solar Effect in the Clouds-Ocean by Gustave Le Gray

What if, late in my life,

an old love returned?

I might get carried away

as I did my first time in that otherworld

ablaze with coney

and neon blue tang,

soundless except for the resonance

of my breath, a hypnotic

one-two, now/then, why not

me, you. I must have seen

the stoplight parrotfish

beam red from a grotto,

but, heedless, sped up,

flippers propelling me over coral

resembling Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia

still unfinished after a hundred years.

Remembering my past,

I circled the remains

of countless marine animals.

Fragile memorials, yes,

but not harmless I’d learn:

the thousand mouths of the reef

that open out of hunger,

alive to the careless swimmer

who comes too close.

One who, succumbing to the pull

of the beautiful, swims out

so far she finds herself at the mercy

of surf that flings her

against the stinging ridge.

Cells meeting cells, tentacles, flesh,

she’s left with the mark

of a fiery ring that burns longer

than a slap. Weeks. Months.

A tattoo that may never fade

from the soft underside of her arm.

Read More

June

By Michael Bazzett

Featured Art: The Sick Child I by Edvard Munch

Stray hair is pulled from the lapel of her favorite

wool coat years later in a secondhand shop, drawn

free in a quick, definitive gesture that could only

be called thoughtless. It settles on the worn carpet

while another woman’s hand holds the hanger and

drapes the coat across her chest—she eyes it

in the mirror with an air of cold appraisal, breath

rising and falling, her chest plumbed with valves

pulsing mindlessly, the forgotten hair underfoot

still holding the map and code of everything

another woman was: the face with the furrowed brow

that could fold and break into a lightning smile,

a woman with a knack for contentment and

quick anger that dispersed as clouds over hills.

An arm slips in and she feels the cool silk lining

on her bare skin. It is June. She does not need a coat

but her mind craves autumn and being wrapped

in well-wrought layers. She slips the other arm in

and hugs herself, snugging the coat to her waist,

wrapping it like a kimono, Yes, she thinks, seeing

an older version of herself walking through a park—

the image comes suddenly, like rain from nowhere.

Read More

Nothing

By Lawrence Raab

Featured Art: Georgia O’Keeffe—Hands and Thimble by Alfred Stieglitz

Why not believe death is also nothing?

—Dean Young

Sometimes nothing’s a glass

waiting to be filled, and sometimes

it’s sleep without dreams, a blank slate

no one gets to leave a message on,

that sheet of water boys skip stones across

to watch them vanish. And sometimes

nothing’s only a word that can hide

what it means inside what it means.

But when I’ve seen death it’s looked

like betrayal, like life taking back

what it promised, slowly picking

our friends apart until nothing

must feel like an answer, and death

slips into the room pretending to care.

Did it brush by me just now,

did it mean to touch my hand?

Read More

The Nod

By Kenneth Hart

Featured Art: Bar-room Scene by William Sidney Mount

Guys like us, we nod to each other

when we pass on the street at night.

We get that things are okay at the moment.

The Nod says, you-don’t-mess-with-me,

I-don’t-mess-with-you. That’s how it is

with guys like us, because the world is a bad place—

that we get—and we get that guys like us

have something to do with it.

But not tonight: you’re black, I’m white, we’re both

black or white, whatever, we’re cool,

nobody’s going to throw hands,

—who said anything about throwing hands?

Because it’s not a look, nobody says

“What are you lookin’ at, dipshit?”

No. The Nod reflects and respects

and steers clear of trouble. It says

we acknowledge our mutual suspicion,

which masks our fear

(we both get that The Nod is part mask).

The Nod: Okay bud, I’d drag you out

of a burning building, you’d pick me up

if I fell off a barstool, cool, we know that,

just don’t ask anything of me right now

unless it’s some kind of fucking emergency.

I’m on my way somewhere.

Read More

Couples

By Kenneth Hart

Featured Art: Underworld Scene with a Man and Woman Enthroned and Death Standing Guard by Robert Caney

Couples who fight in front of you.

Couples who call each other every hour.

Couples who show up early.

Couples who are business partners.

Couples who say “Absolutely.”

Couples who met in rehab.

Couples who sleep with other couples.

Couples who make out in front of you.

Couples who have been divorced more than twice.

Couples who should get divorced.

Couples who say they are not a couple.

Cocaine couples.

Couples who stop having sex.

Couples who tell you they stopped having sex.

Couples who think you don’t already know.

Couples who say “Absolutely.”

Couples you’re related to.

Couples who leave the television on.

Couples who wear matching t-shirts.

Football couples.

Couples who have “an arrangement.”

Couples who finish each other’s sentences.

Couples who have no one else to argue with.

Couples who never argue.

Couples who cancel each other’s vote.

Couples who speak the language of couples.

Couples with nicknames for each other.

Dog show couples.

Couples who stop calling now that they’re a couple.

Couples who start calling.

Couples who die within a month of each other.

Oh look, honey, at ourselves.

Read More

Never Better

By Mark Kraushaar

Featured Art: Kalaat el Hosn (Castle of the Knights, Syria) by Louis De Clercq

On the phone tonight

it’s my ex-wife asking how I am.

I’m fine, thanks, you?

Well, she’s fine too: new place,

friends, job, cousin, pet: perfect.

But now she’s back on her friends again,

friends, food, movies, books and I think,

She sat where I’m sitting now,

I remember, looked out

at the back yard, the neighbor’s car,

the sapling maple at the curb.

She’d have used this plate,

that glass, this chair.

She’s still talking and I like her voice—

politics, work, winter weather—except

there’s this private inside silence going on

and maybe it’s mine but I think it’s hers, or,

it’s a kind of leaning forward through the phone

meaning if we could talk the way we

used to talk we’d know better

where to go and what to do

when we arrive.

We’re quiet

and I can hear her

hear me hear this silence

fill with implication and we’re still.

Read More

Earning a Title

By Jaclyn Dwyer

Featured Art: Bouquet of Spring Flowers in a Terracotta Vase by Jan van Huysum

Your ex is a skinny girl. Skinny like sex-

starved cats, like tigers in Thailand teased

with soccer balls in plastic wrap. Your ex

is a crushed mustard seed. She stains our sheets,

cowers in soft earth, and runs from every room

I enter, wind teasing a tail. Your ex is a sieve,

a fallen kite, Cyrillic G, a flattened hook. You

ask if I love you. I answer, I do. Do you forgive

me? I do. Do you forgive her? I say I do, practicing

for what comes next, for the question she never got

asked. Will you? Do you take? The path to proving

my nubility is through humility. When she mocks

me on the Internet, pokes fun in posts, I laugh too.

Did I say nubile? I mean nobility. Really, I do.

Read More

The Rules of the Game

By Simon Barker

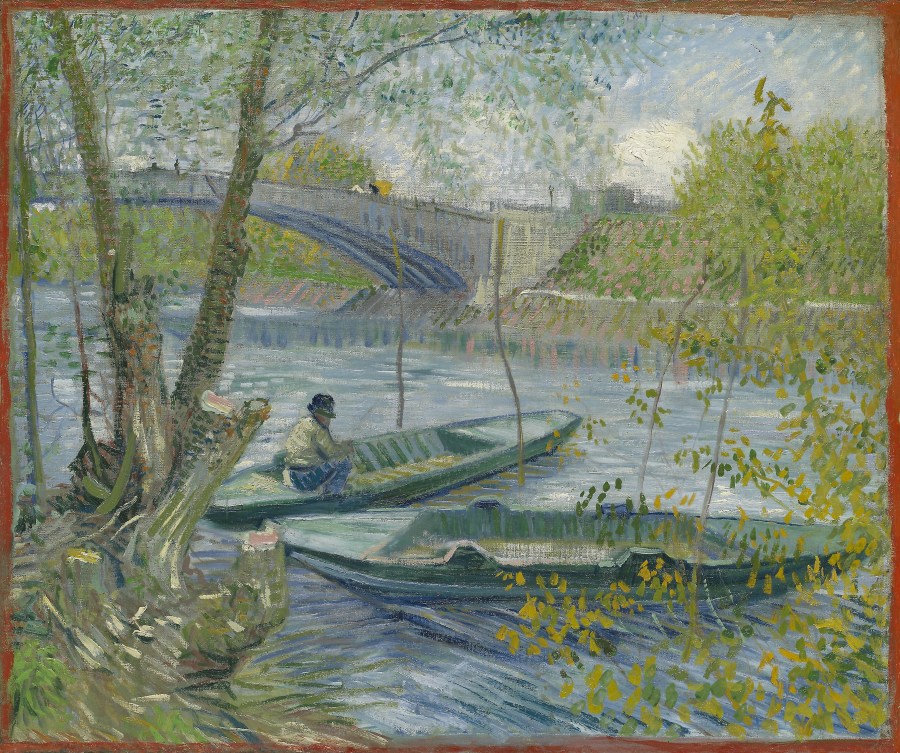

Featured Art: Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy (Asnières) by Vincent van Gogh

I was eating tagliatelle napolitana and drinking imitation Chablis when I remembered that I was supposed to be looking at a house. I said to the others, “I have to go and look at a house.” “We’ll order veal scaloppine,” they said. “We’ll wait for you.” Veal scaloppine was what you ordered at the Mussolini after tagliatelle napoli. The only other thing was grilled liver but Wendy didn’t like the blood so we never ordered it when she was there. Wendy and David had been married for about a year. Wendy was dark-eyed and beautiful and I was in love with her because she was utterly vivacious and she put up with me even though I was an idiot.

I was carrying a map of Sydney but I still got lost on my way to the house. That was one of the habits that made Wendy say, affectionately, “Richard! You’re an idiot!” The house turned out to be across the road from a vacant television factory. When I knocked on the red front door I could hear a cat miaowing. Julie answered in the big, nerdy glasses she wore for studying. She said, “Hi, come in. Watch out for the cat shit, don’t step in it.” But it was too late and I had to leave my sandshoes on top of the steps. The reason there was cat shit was that everyone thought it was Drew’s job to pick it up seeing as the cat belonged to him but Drew was always out. He played the recorder in a medieval band. Julie began by showing me Drew’s room, which was the one at the front. She said, “This’s quite a good room, except when you’re fucking because then people in the lounge can hear everything,” and I thought well, that wouldn’t bother me since I’m not doing any fucking, but I didn’t say so. In any case Drew wasn’t the one moving out so Julie took me to Toby’s room, which was upstairs at the back and not much bigger than the double bed that was covered in Toby’s black satin sheets. Toby’s girlfriend was the sort who was used to black satin. She was the reason he was moving, along with the disco up the street.

Read MoreSweet Spot

By Ange Mlinko

“Sweet Spot” is not available online, but is available for purchase as a part of New Ohio Review Issue 13, which can be purchased here.

Wheels

By Ann Harleman

Featured Art: Car 2F-77-77 by Alfred Stieglitz

1961: ’61 Chevy Impala Convertible

Eddie was the only Catholic boy I knew with a car of his own. It was black with a red top and a sweeping red stripe along each side—a car that swaggered. My mother, impressed in spite of herself (she drove an old Ford coupe the color of cement), made me promise to stay off the Schuylkill Expressway and never to ride with the top down. I agreed, but only because it was December.

Mercy Girls—I was a scholarship student at an all-girls high school, the Academy of the Sisters of Mercy—weren’t allowed to have boys pick us up at school. Not that we would’ve wanted to, since we also weren’t allowed to wear lipstick or jewelry or nail polish, and our uniforms remained deeply dowdy even after we’d rolled up the navy-blue pleated skirts at the waist and unbuttoned the top two buttons on the white cotton blouses. So my first chance to show off Eddie’s car to my friends was at the Junior Class formal, just before Christmas.

Read More

Short Lists on a Diagnosis

By Aran Donovan

Featured Art: A City Park by William Merritt Chase

Ever so rare: the robin’s egg that’s fallen

at the doorstep, as yet untouched by ants

or useless knowledge. A letter mailed from France,

its certain words predestined. New snow, appalling

last spring on cars, mailboxes. Quite rare: the pollen

of narcissus but more rare the bees that dance

their distance. The choreography of plants,

shadow of leaves. St. Francis granting pardon.

More common: construction on the way to work,

the broken earth and open pipe. The trite

condolence of a friend. Misunderstandings

on the phone. The removal of your blouse and skirt

for the new doctor. How it’s come back in spite

of all you’d hoped, your vain and human plannings.

Read More

A Simple Request

By Patricia Corbus

Featured Art: Threatening Sky, Bay of New York by Thomas Chambers

—for Wes

Here I am, still drowning in the world,

while you are opening Dame Simplicity’s closet—

and I say, Be good to him, Simple Goodness,

Air and water, expand for him! Moon, be a smiling

china plate for him to leap over!

In the cupboard where cups wait quietly

and beautiful old words are folded in flannel cloths:

Mother, Father, Long-suffering, Beloved, Forgiveness—

Lay him down in simple peace, homely pleasures,

between jars filled with feathers and shells—

near Grandmother’s broom that sweeps so clean.

What aromatic, wild poultice crushed to the breast

soothes and heals all?—

It is the essence of Brother

overpowering me with some stinging nettle of sweetness—

Whatever sunset door you go through, hold open for me.

Read More

Fault Line

By Margot Singer

Featured Art: Rain Sculpture, Salt Creek Cañon, Utah by William H. Bell

It’s the end of summer and the neighbors have gathered in Evan’s yard, young mothers with babies lounging in the shade on the front porch, older kids racing around the lawn, the men clustered by the grill in back. It is dry and hot, not yet Labor Day, but across the street the upper leaves on the maple in front of Natalie’s house, that precocious tree, are already tinged with red. Natalie wishes it were May again, not August. She longs for the promise of summer rippling outward like the surface of a pool.

Inside, another group of women has pulled up chairs around the kitchen table, mothers Natalie recognizes from around the neighborhood but doesn’t really know, the wives of Evan’s friends. Natalie is still the newcomer, the outsider, Evan’s new girlfriend. The women are bent forward in conversation, a closed set.

“Oh my heck,” one of them is saying. “Here? Really?” She has dark hair with bangs and long-lashed eyes, like a doll’s.

Another woman waves her hand. “It’s public information. Just Google Megan’s Law, you’ll see.”

Read MoreNight Party

By Fay Dillof

“Night Party” is not available online, but is available for purchase as a part of New Ohio Review Issue 13, which can be purchased here.

The Difference Between Us

By Jill Osier

Featured Art: St. Paul’s Choir by Wenceslaus Hollar

Some of my favorite memories of us never even happened.

Like when we sang the “Hallelujah Chorus.” I’m alto, you’re baritone, and it’s

a community choir, maybe a department Christmas party. Maybe we’re at your

alma mater for the holiday concert and can’t help but join in from our seats.

Wherever it is, we know our parts, every word, not realizing we’ve learned them

over the years, overhearing the song in stores and restaurants, doing dishes,

driving home.

And the reason I know this is a memory, that this is not just a fantasy, is because

what I remember most is not the music, not even the sound of our voices. Harmony,

surprisingly, has nothing to do with this.

What I remember and see again and again as they keep playing the song these

weeks of December, is how just your eyes turn, your gaze sliding slowly to the

side to meet my eyes, which are above my mouth, which is singing the exact

words you’re forming with yours—

and this is where memory turns on me, where nostalgia bares its blade: you look

forward again, a motion of such care, such carefulness, like when one’s trying

not to spill. Pure recovery.

Read More

Keyring

By Maura Stanton

Featured Art: And I Saw an Angel Come Down from Heaven, Having the Key of the Bottomless Pit and a Great Chain in His Hand, plate 8 of 12 by Odilon Redon

The keys that disappeared opened what locks?

Upturning every drawer in my old desk,

crawling about the floor with a flashlight,

searching the front walk and the ruined garden,

retracing my steps, retracing my thoughts,

I understand I’ve lost more keys than just

the useful ones that opened my front door.

I’ve lost a set of phantom keys to things

I meant to keep, return to at my leisure.

A demon out of the void snatched them up

so now I’ll never open my lost diary,

or turn the tumbler in my London flat

with a practiced flick, a lock I couldn’t work

without help from the bear-like landlord.

“It’s a Yale lock!” he’d roar. Wasn’t I a Yank?

And now they’ve all vanished, keys to padlocks

clamped on lockers, keys to rusted stick-shifts,

answer keys to the questions I got wrong,

keys to smoky rooms of sex and wine,

keys to old friends’ doors that shall never

open again, and the spare set of keys

to my mother’s house in another state,

empty now except for the pacing cat

waiting for paramedics to bring her back.

Read More

Jonah

By Maura Stanton

Featured Art: Stowing Sail by Winslow Homer

Whoops! He was afraid this was going to happen. He’s been sucked up. The strong wind pulls him in against the stiff fringe of the brush attachment, where he gasps and tangles with bits of debris, strands of hair, crumbs, dust bunnies, specks, soot, and flecks of dander. The brush is swiped across the carpet, freeing him from the tough indifferent bristles. He flies up the silver tube, but since he’s heavier than the rest of the grime, he gets to catch his breath at the bend, pinned against the cold metal until he’s slapped free by a dancing paper clip. Swoop! Suck! Up he goes into the flexible plastic hose. Now and then he catches on the accordion folds, but the air is warmer now, and he feels himself being pulled closer and closer to the engine thrumming in the center. Why, this isn’t so bad. He almost feels excited as he approaches his destination, the special paper bag fitted inside the machine where all the dirt in the house congregates. And then he’s in! He’s dragged through the opening. It’s all over. There’s nothing to do but make a cozy nest in the mound of familiar filth.

Read More

2 Fuzzy Bees

By Maura Stanton

Featured Art: A Gentleman Who Wanted to Study the Habits of Bees too Closely, plate 6 from Pastorales by Honoré Victorin Daumier

“La créateur est pessimiste, la création ambitieuse,

donc optimiste.” —René Char

Because I feared I’d only make a mess

Sticking yellow pom-poms onto black ones,

Or bungle wings as I tried to shape the white

Pipe-cleaners into an outline of flight,

I never opened this kit I got one Christmas

In my stocking—a joke from my sister:

Create A Critter. Since I’m cleaning house

I could throw it away. But all I need

To make 2 Fuzzy Bees are glue and scissors.

Everything’s here—the velvet-tipped feelers,

Button noses, and eyes with moving pupils.

Ages 6 and Up—well, that’s me, isn’t it?

And as an Adult, too, I can Supervise

Myself. So why do I still hesitate?

If I make a bad bee I can toss it out.

Look at this package. The cellophane’s intact,

Directions printed on the cardboard backing.

Even the little loose eyes seem to twinkle

Inviting me to stick them to the heads

Where they belong. Yes, they’re Choking Hazards,

But I’m alone right now, no cats or babies,

And the dining room table is cleared of junk.

And so I do it. Soon my Fuzzy Bees

Are finished, bouncing on their wire legs,

Looking up at me, cute as their photos,

Ready to begin their lives as . . . what?

What have I done? I’ve given them existence.

Their wings will never lift them to the sky,

Their red noses will never scent a rose,

But look at them! Ambitious, optimistic.

Read More

The Lady from TV Is Coming

By Sabrina Jaszi

Featured Art: Dance of the Trojans by Henri Fantin-Latour

Every Sunday my daughter calls from California. “Church today, Mom,” she says, not a question: a truth. Every Sunday I mimic her tone. “DanceCraze at the Lautner Center,” I say, and every Sunday Angelie lets out a tunnel of sigh, long, and black at the edges. Today is like every Sunday. At Messler High this week, I’m teaching orbits: the sun, the moon, and the Earth all moving around each other in perfectly predictable ways. I feel like telling my daughter about it, but I don’t have time. DanceCraze starts at eleven. Usually it’s free, except for next week, when the lady from TV is coming.

Today, as always, Robert snorts as I pass him in my tights and sneakers. I walk the six blocks to the Lautner Center and push through its double doors just a couple minutes early, in time to get my spot in the back but after the chitchat. The clock on the wall is ticking toward eleven and everyone starts marching in place. Lila C. is up on stage between the two droopy flags, with the emergency exit behind her. The crowd today is about one-half oldies, one-quarter hoochies, and the rest children and miscellaneous. Miscellaneous, that’s me.

Read More

1974: The Raspberries

By Campbell McGrath

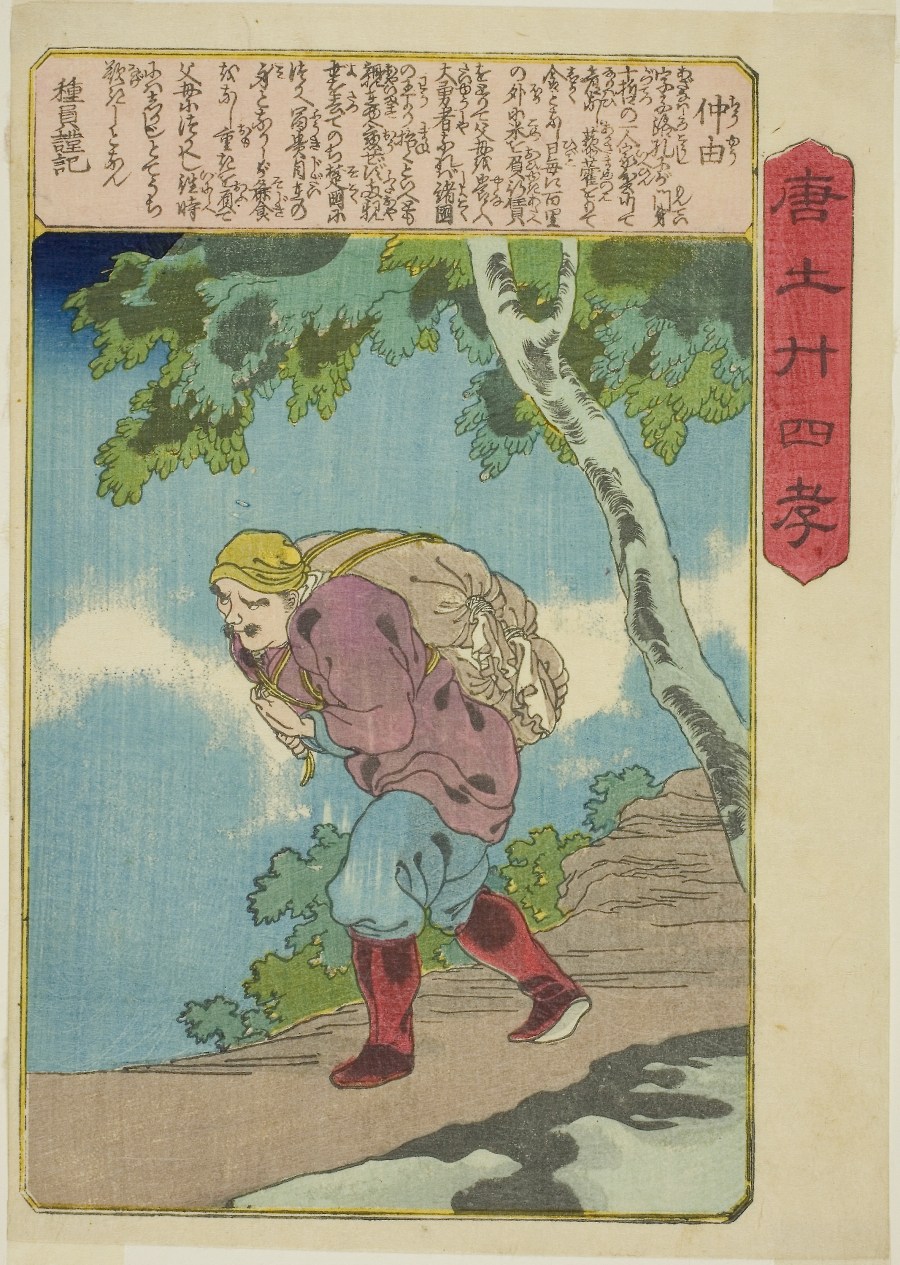

Featured Art: Jung You (Chu Yu), from the series “Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety in China (Morokoshi nijushiko)” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

If it’s true, as they teach in elementary school,

that ours is a secular republic, not gods but men

do our temples and sacred monuments adorn,

then how to explain the immediacy with which I recall

my baptism into the cult of American identity,

my consecration as a democratic individual,

the very first things I bought at a store by myself—

a cherry Slurpee in a collectible plastic superhero cup

and a pack of baseball cards, hoping to find Bob Gibson.

This was at the 7-Eleven on Porter Street,

and soon the five-and-dime on Wisconsin Avenue

cycled into orbit, musty aisles of G.C. Murphy & Co.

where I might spend my allowance on plastic soldiers,

a balsa wood airplane, a rabbit’s foot keychain,

trinkets of no intrinsic worth ennobled by commerce,

aglimmer with the foxfire of mercantile significance,

toys of thought that blazed in the imagination

every step walking home. Not to jingle pocket change,

not to carry a crumpled dollar bill was to drift untethered

from the enormous comfort and safety of the system,

like the astronaut who crosses Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey,

like a Stone Age tribe wandering into civilization

from some last unmapped Amazonian tributary.

Recitations

By J. Estanislao Lopez

Featured Art: The Petite Creuse River by Claude Monet

- The Mountain Recites a Poem

The enunciation of one syllable

lasts two thousand years.

The only mode it knows:

confessional. All it has witnessed,

condensed into a single line.

We’ve compiled the research,

and can say with some certainty

that the first word is Above.

2. The River Recites a Poem

Obsessed with revision, the river

never completes a line. No one

attends its readings anymore

as they go on for months.

Each phrase spills out, then

is sucked back in and altered. This

continues until, by the merciful

winter, the river is shushed.

3. The Sky Recites a Poem

The first experimentalist, the sky

reduces every image to abstraction.

Soap dispenser becomes Absolution.

Mandolin string becomes Disquietude.

Its diction of emptiness surrounds the reader

until he is extinguished—This isn’t murder.

This is nothing but the semblance

of control.

Read More

The Call

By Michael Chitwood

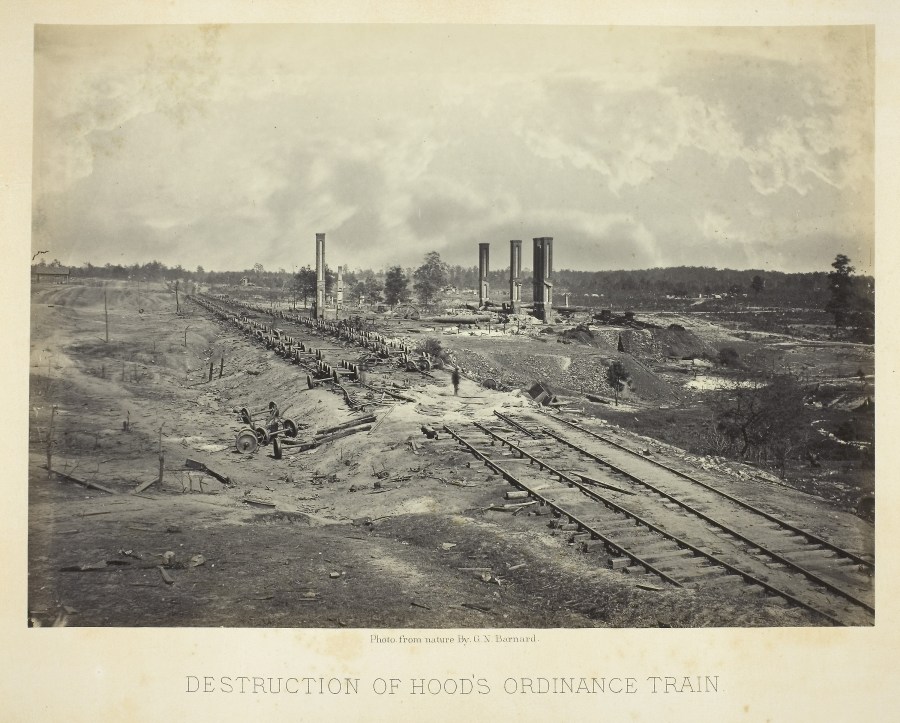

Featured Art: Destruction of Hood’s Ordinance Train by George N. Barnard

There was the rumor

of a deep night/early morning

secret train that a crew

had to be called in for

and they got double time

for their trouble. Big money.

They cleared the tracks for it,

put everything on the side rails,

even the coal cars that were priority.

And when it left the yard

it was only three cars

with a puller and a pusher

so it was jimmy-john scooting

before it was out of sight.

Everyone had a theory.

Some millionaire had a coupe

shipped to Norfolk from Europe

and wanted it in New York by the weekend.

Or the government needed a rocket

pronto to Fort Meade. Or gold—

gold was always a good bet.

No one ever knew for sure

or knew anyone who had been on the crew,

but when the call came,

and it would come, it would,

why sure, sure, you’d go,

that kind of money and all.

Read More

But it Moves

By D.J. Thielke

Featured Art: Ely Cathedral: Galilee Porch from Nave by Frederick H. Evans

Science is nothing to be scared of, I promise my eighth-graders. Science, I say, is what gives us words for what the earth, the universe, already know in a language of cells and change.

They are busy copying my name off the board.

I tell them to think about time, think about how we talk about the abstract idea of it like something physical: a road we’re traveling on. The road of life, we say. Moving past something, leaving it behind; or stepping into the future, looking forward to something. The future is ahead, the past behind, this is how we place ourselves.

But, I say, earlier cultures spoke about time as a road that you walked backwards on. They faced the past, its landscape visible and familiar, while taking tentative, shaky steps into the unknown behind them. The future, a darkness over the shoulder they had to carefully, fearfully move toward.

My students are quiet for a moment.

Then one says, So, life is a highway?

Read More

Title Search for the Italian Ashbery Book

By Damiano Abeni

Featured Art: Tetards (Pollards) by Vincent van Gogh

[The following poem (and its Italian translation) reflect the actual search for the title of a selection of poems by John Ashbery published in a bilingual edition in Italy, and it reproduces the structure of Ashbery’s “Title Search,” from And the Stars Were Shining. The book was eventually published under the title Un mondo che non può essere migliore (A World that Cannot Be Better), translated by Damiano Abeni and Moira Egan, with an introduction by Joseph Harrison (Luca Sossella Editore: Rome, Italy, 2008). The translators thought it was aptly Ashberian that the final book title had not been considered in this search, and that it was derived from a poem not included in the Italian selection: “…while you, in this nether world that could not be better / Waken each morning to the exact value of what you did and said, which remains” (“Definition of Blue,” in The Double Dream of Spring).]

Read More

Feature: Translation Cruxes

Featured Art: Beata Beatrix by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

We asked the distinguished translators listed below to

write about any particularly thorny passages they had

wrestled with, as well as the solutions they came up

with. Their responses follow.

David Ferry

Lydia Davis

Damiano Abeni

Moira Egan

Rosamund Bartlett

George Kalogeris

Joanna Trzeciak

Geoffrey Brock

On Translating Strand and Ashbery

By Damiano Abeni and Moira Egan

Featured Art: Italian Coast Scene with Ruined Tower by Thomas Cole

A few years ago Damiano published the Italian version of 89 Clouds by Mark Strand (ACA Galleries, New York, 1999; 89 Nuvole, Edizioni L’Obliquo, Brescia, Italy, 2003). Some of these one-liners are quite straightforward, but some are really tough to translate. For instance, Cloud # 25 reads: “A cloud without you is only a clod.” Damiano’s main inspiration when translating comes from the approach Glenn Gould had when interpreting a musical score. Rather than focusing on the literal meaning of each word, he tried to play the same game the author was playing, to imitate his wittiness and to leave a trace of the strong cloud/clod alliteration. What came out, when back-translated, would sound something like “A cloud without part of you is almost nothing,” and here is how it looks in Italian: Una nuvola senza parte di voi è quasi nulla.

Read More

On Translating Tolstoy

By Rosamund Bartlett

Featured Art: Spring by Eduard Willmann, after Eduard Marak

In chapter fourteen of the eighth and final part of Anna Karenina, some five thousand words before the end of the novel, Tolstoy produces one of his inimitable, participle-laden, congested sentences about the behaviour of bees in Levin’s apiary:

In front of the entrances to the hives sparkling bees and drones danced

before his eyes as they circled and bumped into each other on one spot,

and amongst them, continually plying the same route to the blossoming

lime trees in the wood and back towards the hives, flew worker bees with

their spoils and in pursuit of their spoils.

Перед летками ульев рябили в глазах кружащиеся и толкущиеся

на одном месте, играющие пчелы и трутни, и среди их, все в

одном направлении, туда, в лес на цветущую липу, и назад, к

ульям, пролетали рабочие пчелы с взяткой и за взяткой.

It is one of those sentences which exemplifies the challenges posed by Tolstoy’s often tortuous but majestic prose in Anna Karenina—a novel he found hard to write due to profound spiritual crisis welling up inside him in the 1870s.

Read More

On Translating Cavafy

By George Kalogeris

Featured Art: The Trojans pulling the wooden horse into the city by Giulio Bonasone

THE TROJANS

As long as our efforts, no matter how hard we try,

Are doomed to fail, we’re like the people of Troy.

Just when the tide is finally turning for us

And our confidence swells, as if we were ready to face

Whatever comes our way, Achilles turns up

Shouting bloody murder, and crushes our hope

With one swift leap from the trench. We’re like the Trojans.

No matter what we do, this always happens–

Though right till the very end we still believe

We still might win, if only by being brave

And not giving in. But once we go out to meet

Our fate, behind our back it bolts the gate.

Even at the eleventh hour, we truly

Believe the gods are with us, defending Troy.

But as soon as we resolve to make a stand

That daring spirit dissolves, like a phantom friend.

Now it’s our worst nightmare, but there we are,

Outside the city walls, running for dear

Life as the sweat pours down, though our legs feel frozen.

Already it’s time to start the lamentation.

And then, high up on the ancient parapets,

Priam and Hecuba weep, weeping for us.

On Translating Szymborska

By Joanna Trzeciak

Featured Art: New York Sky Line, Dark Buildings by Childe Hassam

I got into translation early in life, but instead of playing the field I have tended to go steady and stay with one poet for a long time. My first was Wislawa Szymborska, a Polish poet whom I have translated since the early nineties. Szymborska’s poetry, rife with wit, graceful and deeply humane, has earned her the Nobel Prize, a permanent place in the pantheon of poetry, and admirers such as Woody Allen. Her response to the world is rendered in one of her poems as one of “rapture and despair.”

In the 2002 collection Miracle Fair, I intimated six themes under which her poems might be clustered. One of them is our relation as human beings to animate and inanimate nature. Our attitudes toward other sentient beings is central to poems such as “Tarsier,” “Monkey,” “Seen from Above,” and “Birds Returning.” When it comes to the inanimate world she has devoted entire poems to the contemplation of water, rock, clouds, and sky. Or if not “sky” then perhaps “heavens”? Or maybe “heaven”? The Polish word is niebo [pronounced NYEH boh]. Here we start.

Read More

On Translating Eco

By Geoffrey Brock

Featured Art: Handkerchief by Oriental Print Works

Despite the Italian adage traduttore/traditore, which equates translation with betrayal, nearly all translators I know claim fidelity as their goal (while also admitting the impossibility of perfect fidelity); it was certainly my goal as I set out to translate Umberto Eco’s 2005 novel, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. But what does “fidelity” mean to literary translators? Faithful to whom or what? There is less agreement on that score. The question is complex even with regard to what might be called vanilla prose; it’s deeply vexed with regard to most poetry or any prose that features puns or other word-play, or that contrasts its language with that of one of its dialects, or that relies on allusions that would be clear to source-language readers but opaque or even misleading to others—and so on. In such cases, liberties will often be taken at the expense of semantic fidelity but in the service of broader and arguably more important fidelities. In this piece, I will look at three such cases from Eco’s novel.

Read MoreNew Ohio Review Issue 12 (Originally printed Fall 2012)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

Issue 12 compiled by Natalie Dupre.

Rituals

By Suzanne Carey

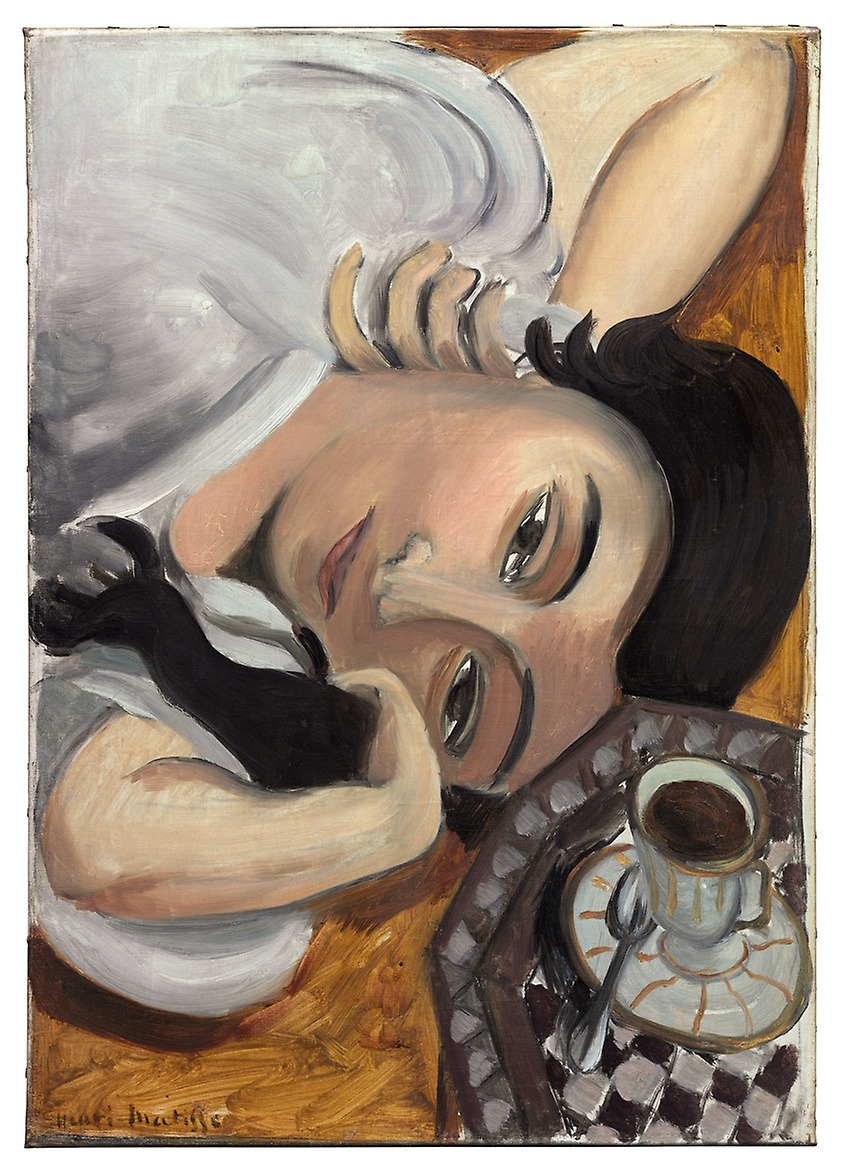

Featured Art: Lorette with a Cup of Coffee by Henri Matisse

After my swim, I sit at a small table at Peet’s

with my medium sugar-free, low-fat, vanilla freddo

that the barista started as I walked in.

I push the whipped cream deep into the cup and worry

about my daughter, who drives

a perilously small car on the freeway,

and my son in New Orleans, too poor to drive,

whose illness frightens me most of all.

My father worried about us until the day he died.

When I came home from college, he insisted

I take the dog or my ten-year-old brother with me

when I drove at night. At eighty-six, he called me daily

from the nursing home to make sure I was okay.

I remember how my mother savored

half a nickel-box of licorice bits and a single cigarette

as she read each evening, waiting for us to come home,

and years later, how she devoured the Hershey bars

and Cokes Dad brought her every afternoon,

long after she had forgotten us all.

Read More

My Father’s New Woman

By Fleda Brown

Featured Art: Fruit and Flowers by Orsola Maddalena Caccia

My father has a new woman. He’s 93, the old one is worn out.

They used to hold hands and watch TV in his Independent Living

cottage, but now there is the new one, to hold hands. The old

one is in Assisted Living not 50 feet away but barely able

to lift herself to her walker. He sits in her room after dinner,

her mind wandering in and out. What if she escapes

and comes over while my father is “taking a nap”

with this new one? My mother is two miles away beneath

her stone, relieved. I bring artificial flowers to her with my sister,

who likes to do that when we visit. I am not much for

demonstration. I would just stand there and say, oh, mother,

he’s at it again. And she’d say, I am sleeping, don’t bother me

with him anymore. And we’d commune in that way that knows

well enough what we’re not saying. And I’d be lamenting

my self-righteous silence in the past, my smart-aleck-motherjust-

go-to-a-therapist talk. What I should have said was, was,

was, oh, it was like a tower of blocks. Pull one out and all

would fall. She would get a divorce and a job and marry some

balding man like her father, who would be my ersatz father

and would take her dancing and let her wear her hair

the way she wanted, and she would cut it short and get it

permed and life would quiet down and my father, to her, would

morph into the handsome and funny Harvard Man he was

in the old days, the way he posed her for his camera, tilting

her head to the light with his devouring-passion fingertips

and her days would begin to feel like a succession

of pale slates to scribble on and erase before the new husband

came home from work, while my father would spin off

after whoever would “put up with him,” as he says,

and would follow his new one around carrying her groceries

and complaining that she spends too much, but biting his tongue

and thinking how soon she would let him, well, you know,

and I would be, what? The same as now, writing this down

so that none of the shifting and sifting could get away

cleanly without at least this small consequence.

Read More