Looney Tunes

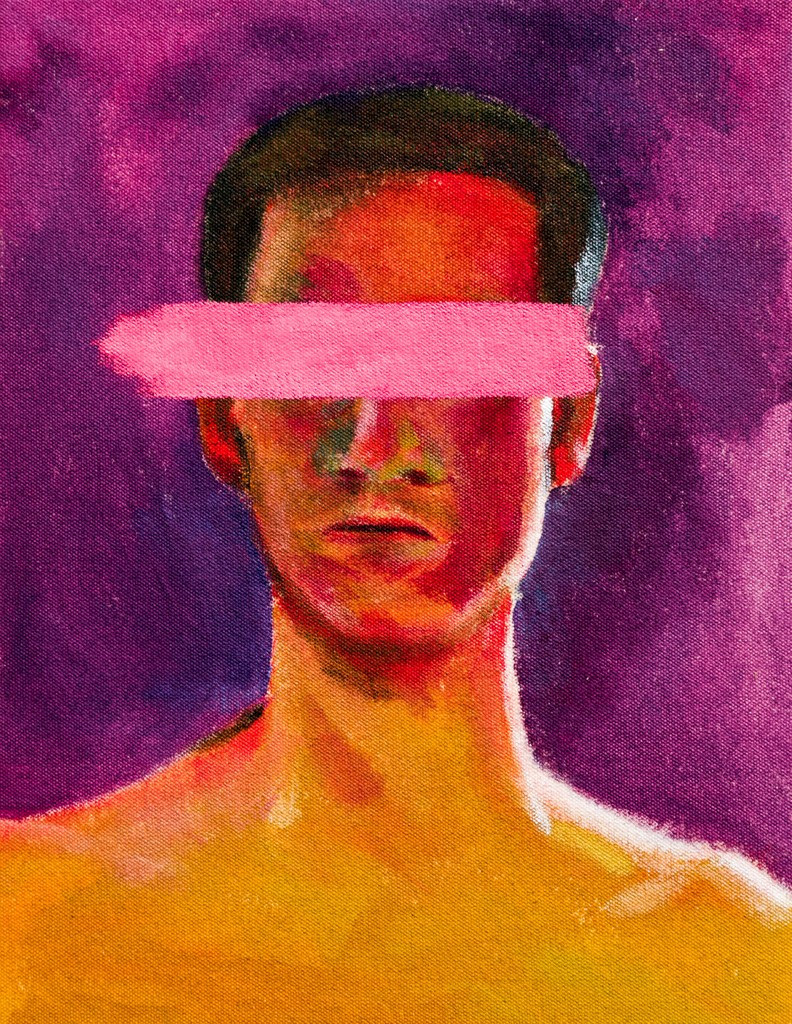

By Nathan Anderson

Featured Image: Summer Morning by David Lucas, 1830

Nah, it’s not that, I wouldn’t call it that, I mean molested

that’s like TV stuff, and Brenna

she’d be real nice sometimes like flesh and blood should.

Bring me back a chocolate frosty just because.

Anyway, I’d just as soon say we’re done,

or you want I should go through it all like I did in June

with the last one? Twice now—and this just goes to show

the system’s jacked—twice I’ve waited, asked the front desk ladies

and waited, I said people I need a little help and you’re telling me two hours?

In all this hospital you’re telling me there’s no one I can talk to now?

I said what about the dude mopping floors? Is he around?

Can I talk to him? Or do I go ahead and slit my wrists right here?

So they hauled me up to you, another white coat

working the psych ward. A woman. What’s up with that?

No offense or nothing. That’s just how they do me

down on first-floor, where everyone else on earth is. You ever one of those

ER docs I see running around? The way I figure it, a woman like you

doesn’t need to run. You’re all put together—you know, like a car

that’s just come off the line . . . . But okay, this isn’t about you.

Inspiration

By Mark Kraushaar

Featured Image: Mountain Landscape with Bridge by Thomas Gainsborough, 1783/1784

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Intellectual: Anyone who can listen to Gio-

achino Rossini’s William Tell Overture with-

out thinking of the Lone Ranger.

—Laurie Taylor, sociologist

Sometimes I picture that foppish, fat Gioachino Rossini—

with his brocade shoes, his velvet-collared jacket and his satin vest.

But mostly I think of him stepping over the ocean, smiling

and rubbing his chubby palms and then, inexplicably,

standing on the porch of a modest family farm

and looking out at Bald Rock Dome or Sugar Pine Peak.

Beside him a poorish, but kindly, but cowardly widower

explains that just that morning a band of filthy varmints

burned his barn and shook him down for the last of his cash

and his only cow. Rossini listens but begins to hum

and just as he turns from the farmer to gaze back at the mountains

two handsome men gallop up and dismount.

The first, the one with the matching six-guns,

and black mask and elegant horse,

hands the farmer his recovered money.

The second man, his sidekick, a quiet Indian

dressed in buckskin and moccasins says:

Bad men go jail.

We ride kemo sabe?

Yes, Tonto, says the mysterious rider

and pausing only to wave

the two men speed away in a cloud of dust.

Once again the Italian Mozart looks out at the mountains

and begins to hum. Who was that stranger with the mask?

he asks, I wanted to thank him.

Read More

That’s Me Smiling in the Back Row

By Elton Glaser

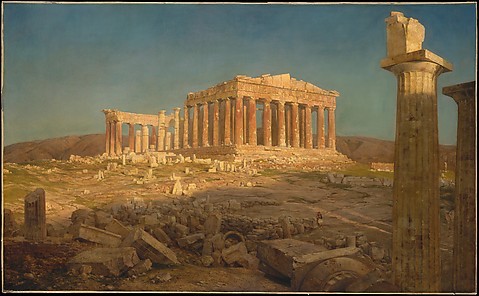

Featured Image: The Parthenon by Frederic Edwin church, 1871

The day warms up fast,

Like leftovers in a microwave, odors of dawn

Still rising from the dead lilies,

From dry grass bleached to blonde and now

Heading toward platinum.

In the slow burn of midsummer,

The nose takes you where the mind won’t go.

There’s bad juju all over the place.

Light clings like cellophane

To the limp leaves. Nothing will budge

That carpet of shadows on the back porch.

I’m watching a spider

Rappel from the blades of a broken fan.

Somebody needs to fix it soon,

Somebody who knows how to work a miracle

With Juicy Fruit and a steak knife.

May B

By Lois Taylor

Featured Image: Young Ladies of the Village by Gustave Courbet, 1851-2

The last thing May B ever wanted was to be stuck with Tweety, who is standing there in her halter top and shorts, frowning at the yowling cat.

“Run that by me again, where you got her?” says Tweety.

May B explains how the stray came to the door just before her mom got sick and the aid car had to take her away again, and her mom said the cat was pregnant but way too young to have kittens.

Now the cat begins to twitch. “She’s going to die,” says May B. “She doesn’t even have a name.”

“Who’s talking about dying,” says Tweety. “Help me get that baby ready.”

Read More

Venus Out on the Town

By Shakira Croce

Featured Image: Charlotte, Lady Watkin Williams-Wynne by Daniel Gardner, 1775

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Yes, you may buy me

A drink

It has been a long week for me too

At work trading, you said?

No, you haven’t had much?

Experience in social enterprise

Isn’t it great we live in a country

Where you and your partners can pull such fine bootstraps

One of the brightest, yes

I’ve been told I have a nice smile among other things

Your lines show in a few more years

Your advances will be harmless, cute even

Thank you for the champagne

What did you say your name was?

The Tenants of Feminism

By Denise Duhamel

Featured Image: The Valley of the Seine, from the Hills of Giverny by Theodore Robinson, 1892

When the interviewer mishears “tenets”

I know my gals are not in a villa,

never mind the United States Senate.

My heroines crowd in drab tenements,

their image scaring even Attila

the Hun. The interviewer hears “tenants”—

bad asses, public housing. Bob Bennett

wakes sweaty from a nightmare, Guerrilla

Girls rushing the United States Senate;

Gloria Steinem, bell hooks, and Joan Jett

stuffing manifestos in manila

mailers. The interviewer hears “tenants,”

sees kitchens where women cook venomous

dishes. His lady smells of vanilla,

minding their house, not the U.S. Senate.

My principles are not set in cement,

nor are they adrift on a flotilla.

I call upon all feminist “tenants”—

Steer your U-Hauls to the U.S. Senate.

Read More

We Are All Beyond Disgusting

By Jill Kato

Featured Image: Breezing Up (A Fair Wind) by Winslw Homer, 1876

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

I like to get to the ship early. You’ll usually find a couple of old-timers waiting by the bar, itching to sip a Tom Collins or a whiskey sour on the rocks and get their vacation started right. This is the best time to build rapport and I’m their gal. At this point, they’re still excited about their trip and have a thick wad of cash in their billfolds. Their wives are in their cabins getting settled or making appointments at the spa or booking excursions for when we dock. The bar is quiet and they have me all to themselves. They can pour out all their troubles, and I can pour them all the liquor they need, at heavily marked-up prices. I haven’t even finished restocking the tabasco and maraschino cherries when a salty dog of a guy walks in. His name is Jerry and he’s on board to celebrate his wife’s sixty-fifth birthday. I ask him what he does, and he says he used to own a manufacturing company in the fashion district but now he’s retired. Left the business to his son. He says he built his company from scratch. Even though his shirt is ugly and has hula girls on it, I tell him I like it. I tell all men I like their shirts. I garnish his glass with an orange slice and tell him I admire men like him, self-made men who do things like run their own companies. And I do.

Read More

The Lake

By Billy Collins

Featured Image: Lumber Schooners at Evening on Penobscot Bay by Fitz Henry Lane, 1863

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

As usual, it was easy to accept the lake

and its surroundings,

to take at face value the colonies of reeds

along the shore, a little platoon of ducks,

a turtle sunning itself on a limb half submerged,

and the big surface of the lake itself,

the water sometimes glassy, other times ruffled.

Why, Henry David Thoreau or anyone

even vaguely familiar with the role

of the picturesque in American

landscape painting of the 19th century

would feel perfectly at home in its presence.

And that is why I felt so relieved

to discover in the midst of all this

a note of skepticism,

a touch of whimsy,

or call it a bit of Dadaist playfulness;

and if not a remark worthy of Oscar Wilde

then surely a sign of the human was apparent

in the casual fuck-you attitude

so perfectly expressed by the anhinga

that was drying its extended wings

in the morning breeze

while perched on a decoy of a Canada goose.

Read More

Regarding Isabelle Huppert

By Tom Whalen

Featured Image: The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (from the Unicorn Tapestries), 1495-1505

Yesterday as I reread Hubert Hoskin’s translation of C. A. van Peursen’s Leibniz (1966/69), I couldn’t help but think of Isabelle Huppert. As with Leibniz, experience alone cannot account for her performances, but I don’t think, regarding Isabelle Huppert, I need concern myself with eternal truths residing in the mind of God. Judge advocate, nun, prostitute, mother, dressmaker, postal clerk, piano teacher, scientist, abortionist, war bride, writer, hostage, thief—whatever the role or source (Euripides, Diderot, Goethe, Dostoyevsky, Flaubert, Maupassant, Conrad, James, Zamyatin, Crnjanski, Genet, Bataille, Duras, Highsmith, Bachmann, Rendell, Jim Thompson), energies feed the performances of Isabelle Huppert from without and within.

Have you seen many of her over one hundred films? Retour à la bien-aimée, for example, or Eaux profondes, Pas de scandale, Sans queue ni tête, La séparation? Are you older or younger than Isabelle Huppert?

At the door to the house of Isabelle Huppert one stands as if before a tabernacle of dreams. Have you, too, stood before the tabernacle of Isabelle Huppert, or perhaps even entered its elegant chambers, which others before and after you have also entered? I confess I have not, though I am convinced I can say without equivocation that the house of Isabelle Huppert is capacious, albeit modestly so.

Read More

On His Way in Finding the World

By Dennis Sampson

Featured Image: The Lackawanna Valley by George Iness, 1856, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

He was a person. He put

one foot in front of the other and often

thought of himself before thinking of others,

tried at times to ask a woman whom he loved

what he had done wrong and sobbed

during a counseling session in a back room of

a Catholic church when his wife made it clear she

did not want him to touch her. He smoked,

wrote in enclosures that were cold, that were sweltering,

and celebrated his modest accomplishments

by drinking alone in a bar in Cleveland,

infuriating those who did not like his kind

of frankness. When his mother

died slowly after a stroke he felt nothing. The singularly

vivid iridescent streak of sunlight in late afternoon in October

inspired him to write. He never forgot

the aroma of Mennen after-shave permeating the hallway

when his father left the bathroom, or the sweet fragrance

of lilacs growing in all corners of their yard. A person.

And he once held a leopard frog in his palms and was

startled by how desperately it wanted to get out.

Read More

Rumors About Dread Mills

By Rodney Jones

Featured Images: Rouen Cathedral, West Façade by Claude Monet, 1894, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

1974

At last they have him in church, a short service and the family silent, but the moments after the funeral are like a test.

True: The new base-tube press at Lockland Copper weighed sixty-seven tons. When they had completed the building and brought it in the door, six engineers agreed they would have to lift the roof to get the crane in and lower it into the pit. He heard from Tip Smith, a drinking buddy, a welder on the job, and wrote the board, saying he would do it for 10,000. Went to the ice plant, ordered eigh- teen blocks, filled the pit, rolled the press onto the ice; then, as the ice melted, pumped out the water.

True: Drunk every day for sixteen years. False: Mostly homebrew or moon- shine.

True: Every morning Maurice Orr’s rooster pissed him off. False: He caught the rooster in a sack, dug a hole behind the house, buried it with just the neck and head sticking out, cranked the mower, and mowed the lawn.

False: The story that besotted on the back lawn he ordered Jawaharal to dance and choreographed the steps with a Colt revolver. (Gunsmoke.)

True: Jawaharal inherited his logic gene and argued when he called him “Jerry.”

False: He never hit a lick at a snake. Once he pruned the grapevine. Twice, after midnight, he picked roasting ears from Leldon Spence’s garden.

True: When the money from the press job ran out, he wrote bad checks until his name was published on the glass doors of every business from Cold Springs to Decatur. It hit him then one day: go from store to store, copy all the names, print the list of deadbeats twice a year and sell subscriptions to each store for fifty dollars.

True: His Deadbeat Protection Flier taking off before the Credit Protection Act: drinking Jim Beam in the air over Georgia and Louisiana, he was a sloppy man who made a million dollars.

True: The gay son home from Palo Alto. The wife, a holy roller in a sari. His brilliant, inebriated redneck math, marks in the chicken yard. The liver. The heart—details of the unannotated life: grease-prints on Erdös in Combinator- ics, unused tickets to see Conway Twitty—Cliffs Notes for Abyss Studies—

His mind at the end like a hand reaching for a pocket when he wasn’t wearing a shirt.

“I would kill myself if there were anyone better.”

Read More

The Ends of Stories

By Karen Loeb

Featured Image: Soir d’hiver à Montmartre (Winter Evening in Montmartre) by Jean-Alexis-Joseph Morin-Jean, 1910; Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

At the finish of the meal, your father left. And that was that.

I led a reckless life, but when the accident happened, I reformed.

So I discovered that the bananas had to be really ripe.

The bouquet was a wet bathing suit moldering in a gym bag

tossed in the corner last month.

The lost earring with the green stone turned up years later

when they moved the dresser. She’d thrown out the matching one

a decade earlier.

The smell was a casserole forgotten on the counter. Something with tuna

and onions. It greeted them when they returned from vacation.

I plan to beat the odds and live forever, he declared.

The cat was hiding in the top drawer of the bureau, flattened

as thin as a comic book, eyes peering up, blinking, when we

finally found him.

Turned out it was a moth as big as a bat making those shadows

on the cabin wall.

She went shopping for a jacket covered in feathers, just as it had

appeared in her dream.

Read More

BBC

By Mike Wright

Featured Image: View of Toledo by El Greco, 1599-1600

I leave the World Service

on at night, snoozing through

the British iteration of gang rape

and kidnapping. I’ll stir sometimes

to hear a few moments of economic

collapse, but it’s really white noise,

blanching the laughter of drunks outside.

Sleeping to tragedy helps tamp down

my father’s last days, his morphine speech,

how my mother sent me to Kentucky

Fried Chicken with a coupon

for his last meal, and how shame

drove me to throw the coupon out.

If his death were broadcast in the night,

his of thousands of dying fathers,

and you slept well, how could

I begrudge you a night of rest?

Read More

Where My Father Went

By Sandy Gingras

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

When the funeral director hands my father’s ashes to my mother, she puts the little cardboard box into her pocketbook—the one with all the zippers and buckles. My mother says she’ll hold off on scattering the ashes until maybe the next time my brother comes down from his farm and we’re all together. Maybe we’ll scatter them in the ocean.

“But, for now,” I ask, “Where are you going to put him?”

“In my bedroom closet,” she says.

My parents never shared a bedroom. My father’s room was the converted attic, my mother’s, the converted garage. As far away as they could get from each other within the same house. Putting him in her bedroom closet seems, at once, too remote and too intimate, but I don’t say anything.

Two years pass.

My brother only visits on Christmas and Thanksgiving, which is not the right time to scatter the ashes. It’s never the right time to scatter the ashes.

Read More

Someone Else

By Sandy Gingras

Featured Image: Roses by Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

When my mother was dying, we started calling her “Grammy” as if she’d become someone else. She was eighty-five pounds. She looked like a shrinkydink of herself. She wore a diaper and a hospital gown. The diaper looked enormous on her. It was one of those pull-up ones. If you yanked up her diaper when she was trying to stand, you could lift her right off her feet. “Whoa,” she’d say to you. “Whoa there.” Grammy was a good sport. She was nothing like my mother.

She was on morphine, so a lot of the time, she made no sense. “You know,” she’d tell me earnestly, “I gotta get me a Louie-Louie.”

“Okay,” I’d tell her, but I didn’t have a clue what she meant. “I’ll buy you one.”

“Don’t get it too small,” she’d say. “Oooh,” she’d kind of shiver with excitement, “That will be lovely.” Lovely. As if my mother would ever say a word like that.

Read More

My Mother Comes to Dinner

By Sally Bliumis-Dunn

Featured Image: Green Plums by Joseph Decker, 1885

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

We leave the dining room and she remains

alone at the table; the plates need washing,

we prepare dessert. I still wait for her

questions, half-buried in dish-clatter,

her broken tones in the hot kitchen air,

though these days she sits mostly silent.

And larger than the room and yellow walls, her silence—

as though it were strung to the sky,

to the air that too has been washed and washed

like a bed sheet in the relentless sun,

colors and patterns mostly faded

like all the meals enjoyed then washed

from these brown earthenware plates.

Read More

Jester’s Cap

By Brandon Amico

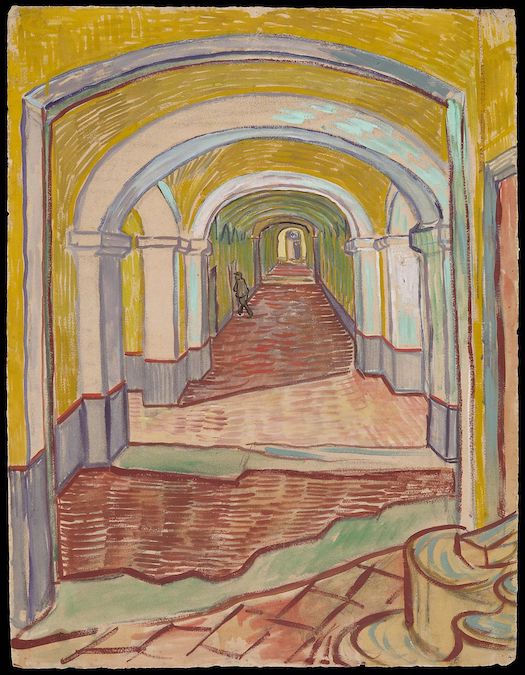

Featured Image: Corridor in the Asylum by Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Three rabbits walk into a bar. The third rabbit carries a shotgun.

Three rabbits walk into a bar. The third rabbit carries a shotgun and the first

rabbit a vase of imported flowers.

One of the rabbits is already drunk.

Three rabbits walk into an orgy but only for the pre-orgy hors d’oeuvres.

Three rabbits walk into a bar with masks on but their ears give them away.

Knock-knock. (Who’s there?) No one, it’s just the second rabbit, the one with a

free hand, rapping his knuckle on the bartop.

Banality

By Gregory Djanikian

Featured Image: Tullichewan Castle, Vale of Leven, Scotland by Sir James Campbell of Strathro, 1855

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

There’s something to be said for banality,

the way it keeps everything on a level plane,

one cliché blithely following another

like cows heading toward the pasture.

How lovely sometimes not to think

about Russian Futurism, or the second law

of thermodynamics, or how thinking itself

requires some thoughtfulness.

I’d like to ask if Machiavelli

ever owned a dog named “Prince.”

I’d like to imagine Rosalind Franklin

lounging pleasantly by a wood stove.

Let the mind take a holiday,

the body put its slippers on.

It’s a beautiful day, says the banal,

and today, I’m happy to agree

with its genial locutions.

Nowadays

By Judy Rowe Michaels

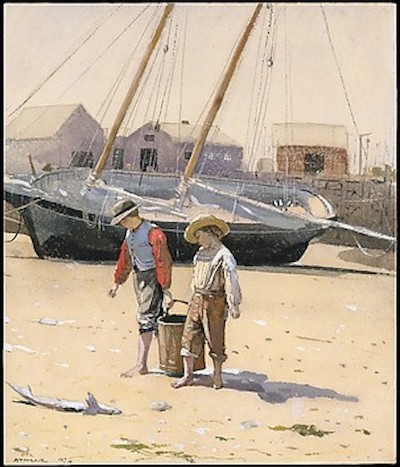

Featured Image: A Basket of Clams by Winslow Homer, 1873

And is that everything

since you? Since meaning

posthumous.

Here melancholy’s

interrupted by brief flirt

with dictionary: originally

postumas, no hint

of burial in living earth.

Dicking around again with

missing you, post this and that—

coital, colonial, menopausal,

Mesozoic, coitus interruptus . . .

Nowadays sex is catch-all for

almost anything, god, war,

cupcakes, abs and apps, the boat

is listing.

Poet Gilbert, Jack, said

“the erotic matters not as pleasure

but a way to get to something

darker.” He’s restless

when people laugh a lot,

he prefers Greek fishermen,

who “do not play on the beach.”

Is it so wrong to heft

an inflatable ball, twirl it

on a finger, think circus seals?

Wasn’t sex mostly three-ring

circus—three or more, given

the presence of memory, fantasy,

irony, flattery, usury, syzygy—

that’s sun, moon, earth aligned,

and then there’s the all-but-impossible

synergy, two becoming a

greater third,

yes, Nowadays

is everything since that.

Read More

Harping

By Judy Rowe Michaels

Featured Image: Cattleya Orchid and Three Hummingbirds by Martin Johnson Heade, 1871

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

While most of us are grieving

something—cold spring lost child dead-end

lyrics that won’t resolve,

the spadefoot toad, who bears

a gold lyre-mark on her back,

is crazy-busy with what science calls

explosive breeding. Rain says Go,

and up from culvert cistern over porch and patio across roads

the fraught migration of spadefeet slowly breaches

our borders to breed in our ponds.

Flood of toadlets in just three weeks, pop pop,

with tiny golden harps, how will this

end? We run them down

coming or going, then pronounce them

rare, so we

love them, make posters, poems—

(Old moss-grown pond—a

toad jumps in to breed pop pop

poppoppoppoppop)

We can’t say they’re unnatural, or blame

the job rate bad schools gang wars (unprotected

sex?), but tiny golden harps

seem suspect artsy irresponsible un-American.

All night trill thrills,

while most of us are grieving.

Read More

Feature: Uses & Abuses of Dialogue

The following is a collection of essays and writings on the subject of dialogue within fiction. Including an essay from author Rebecca Makkai (Music for Wartime, The Hundred-Year House) about a college assignment of eavesdropping to craft realistic dialogue. As well, audio of Robert Anthony Siegel reading “I Deserve Two Firing Squads: Dialogue and Conflict in Fiction.”

A Trompe L’Oeil for the Mind’s Ear

By J. Robert Lennon

Featured Image: Lady Lilith by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1867

The key to writing realistic dialogue in fiction is to abandon all presumption of authenticity and acknowledge the necessity of total fakeness in achieving the illusion of truth.

Human speech is not simple. The words we say in conversation convey, at best, 25% of what we mean,1 with the remaining 75% taken up by body language, volume and tone, facial expression, and prior understanding between parties. The fiction writer has access to these conversational elements, of course, and may fill in back story, provide stage direction, and apply (judiciously, lord help us) descriptive dialogue tags to convey the intended meaning. But a good writer can evoke the character of a speaker, his or her intended and actual meaning, and even very subtle contextual clues, using only the words within quotation marks.

Among the tools the writer has at her disposal when writing dialogue: Sentence length. Punctuation. Rhythm (along an axis of consistency, from entirely smooth to completely broken). Syntax and diction (specifically, its breadth, expressive sophistication, and degree of formal correctness). The reader should be able to understand who is speaking in the same way that he requires no assistance to identify, by sound alone, the voices of his friends in a crowded room.

Read More

Inside the Cave-Speak of Saunders

By Leslie Daniels

Featured Image: Still Life by Henri Fantin-Latour, 1866, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

The setting in George Saunders’ story “Pastoralia” is a theme park where two characters—the narrator and Janet—live and work in a simulated cave. Their job is to perform for the occasional tourist the skinning and roasting of a goat. Theme park rules dictate that employees must not speak English at any time so as not to destroy the illusion of being cave people. The narrator abides by the rule, but Janet flouts it, which is a major concern of the narrator’s. On this occasion the freshly dead goat has not been delivered. There are no tourists present.

Janet comes in from her Separate Area and her eyebrows go up.

“No freaking goat?” she says.

I make some guttural sounds and some motions meaning: Big

rain come down, and boom, make goats run, goats now away, away

in high hills, and as my fear was great, I did not follow.

Janet scratches under her armpit and makes a sound like a mon-

key, then lights a cigarette.

“What a bunch of shit,” she says. “Why do you insist, I’ll never

know. Who’s here? Do you see anyone here but us?”

I gesture to her to put out the cigarette and make the fire. She

gestures to me to kiss her butt.

“Why am I making a fire?” she says. “A fire in advance of a goat.

Is this like a wishful fire? Like a hopeful fire? No, sorry, I’ve had it.

What would I do in the real world if there was thunder and so on and

our goats actually ran away? Maybe I’d mourn, like cut myself with

that flint, or maybe I’d kick your ass for being so stupid as to leave the

goats out in the rain.”

I Deserve Two Firing Squads: Dialogue and Conflict in Fiction

By Robert Anthony Siegel

Featured Image: Landscape with Trees and Water by James Bulwer

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

The world I grew up in was full of hyper-verbal people for whom talk was the medium of both ambition and feeling, the tool they used to try to shape the world around their desires. For that reason, when I began writing fiction, I found that characters were never completely real to me until they spoke: when they started talking I finally knew what they wanted. So I started writing the dialogue first. I would get two characters talking to each other and then build the scene out from their conversation. The dialogue was the trunk, and everything else branched out from it: thought, feeling, memory, sense perception, action.

In those days, when a scene worked, I thought it was because the dialogue was good. It took years for me to realize that it was the other way around, that dialogue was just helping me to uncover the underlying conflict that actually drove the story. What I know now is that dialogue doesn’t have to be fancy or quirky or unusual in order to do its job effectively. It just has to arise freely and naturally from the characters’ experience of conflict.

Read More

A Brief Personal History of Dialogue

By Kelly Luce

Featured Image: The Great Statue of Amida Buddha at Kamakura, Known as the Daibutsu, from the Priest’s Garden by John La Farge, 1887

Not everyone says what they mean. But they do

always say something designed to get what they

want.

—David Mamet

1987: Ms. Voyeur, my first-grade teacher, tells my mom I’m too quiet and should be seen by a psychiatrist. But I prefer listening! Other people are interesting. They tell you more secrets when you’re quiet.

1992: My Language Arts teacher accuses me of plagiarizing a short story I wrote about volleyball tryouts. Why? “The dialogue is too realistic.” When I tell her that’s because I just tried out for volleyball myself and remembered how the girls sounded, she says, “No one learns to write dialogue by listening to real people talk.”

1997: I read Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” for the first time. Remember the conversation between returned soldier Seymour Glass and the young girl, Sybil, on the beach? Sybil is being perfectly herself, still possesses her childlike ability to say just what she means. Seymour is a couple hours away from—. Their chatter is innocent. Or is it terrifying? Take this exchange about a rubber raft:

Read More

The Dialogue of Gesture and Silence

By Alyce Miller

Featured Image: Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight by Claude Monet, 1894

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

What people don’t say is often as important as, or even more important than, what they do say. Too much exposition, or what I call “soap opera dialogue” (e.g. “You remember my brother John who tried to murder Tiffany, before she was caught stealing from Marsha’s cousin who changed her name….”), or its opposite, too little, as is often found in the “generic social glue” of the how’sthe-weather variety, can undermine the progression of story and essential character development (unless, of course, weather is key to the story).

We often think we learn about people through what they say and how they say it, but other forms of communication are just as crucial. Dialogue can happen without speech. Words can fail. Gesture can summon meaning beyond language.

In Hemingway’s dialogue-rich story set in an empty train station in Spain, “Hills Like White Elephants,” the two traveling protagonists he calls respectively “the man and the girl” carry on what might sound to the untrained ear like a conversation about nothing when, in fact, they are about to make an important decision as to whether “the girl” should have an abortion. Whichever path they choose, it is clear that the course of their life together will be forever changed. At one point, after a good deal of back and forth, the girl says, “Then I’ll do it because I don’t care about me.” When the man counters with “I don’t want you to do it if you feel that way,” the girl doesn’t respond. Instead she stands up and walks to the end of the station. Her choice to substitute action for speech and distance herself momentarily from the man says more than anything she could at that moment. Her attention drifts instead to the landscape, the river on one side of the track and the mountains on the other, while she stands in that place of in-betweens and uncertainty. No conversation could convey her dilemma more precisely at that moment.

Read More

Dialogue: The Footfall of Its Wandering

By Darrell Spencer

Featured Image: The Card Players by Paul Cézanne, 1890-2

You might not have it in mind to go a particular

direction and you might end up going that way.

—tapper Jimmy Slyde

Well, that ain’t what art does. It makes things.

—Stanley Elkin

1. Full Disclosure

For my entry into a discussion of dialogue I can’t think of a worthier writer to cite than Amy Hempel. The magician and maestro. Hempel’s narrator of Tumble Home opens the novella as one ought: “I begin this letter to you, then, in the western tradition. If I understand it, the western tradition is: Put your cards on the table” (69). Here are my cards: I like fiction that feels off-shot and shaggy, that seems to have fallen from the sky and is banged up thanks to re-entry. I like my fiction jerry-rigged and clumsy. Stanley Elkin uses the word baggy to describe his novels. Perfect.

Screw Poe: “A skillful literary artist has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents—he then combines such events as may best aid him establishing this preconceived effect.” Oy. Rube Goldberg schooled me; he’s my guy. I want, as I read, to experience the acrobatics, to hear the pop and the hiss and the whiz-bang of the performance. A Goldberg contraption might get you somewhere but you will most likely be too dizzy to appreciate your arrival. You’ve seen those spaceships wobble across the screen in the crackly black-andwhite Flash Gordon flicks. That’s what I’m talking about. Look closely and you see the wires.

Read More

That Dialogue Assignment

By Rebecca Makkai

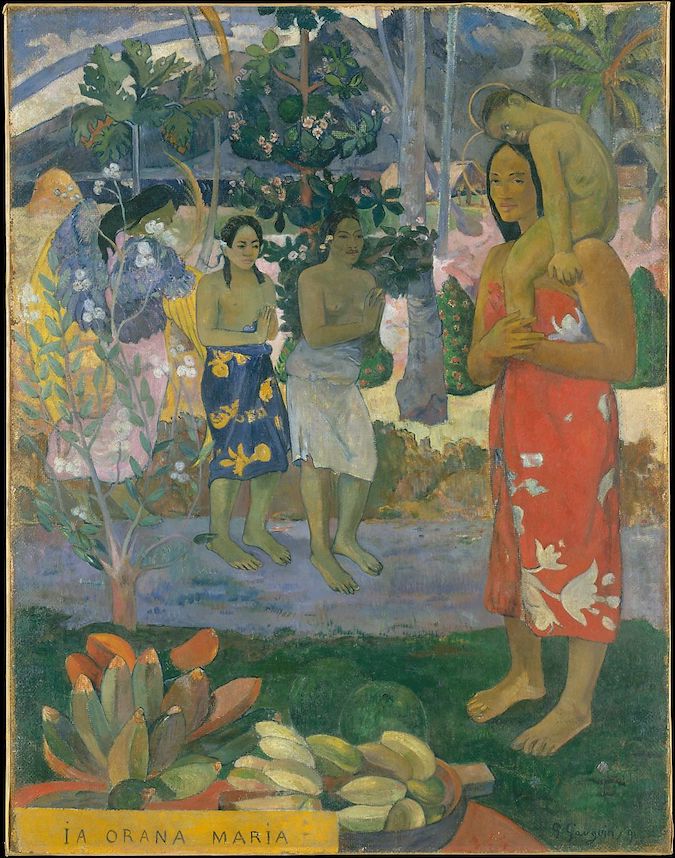

Featured Image: la Orana Maria (Hail Mary) by Paul Gauguin, 1891

I first got The Assignment in a college playwriting class. You might have gotten it in high school, or picked it up from a writing exercise book (somewhere between Keep a Dream Journal and What Color Is Your Character’s Toothbrush?): Eavesdrop on strangers, and write down everything they say. The idea is that this will help you write better dialogue, more realistic dialogue. Because realistic must equal better.

To be honest, I fudged the college assignment somewhat. I listened in on two campus maintenance workers, thinking they’d say hilarious and off-color things. Mostly, they grunted about paneling. I cherry-picked my hour of listening for the best phrases, crunching them together into what sounded like three minutes of witty banter, adding a few lines of my own. I did this partly to make my classmates laugh (I knew we’d be reading this aloud the next day) but also because I sensed that there was something deeply unsatisfying about actual dialogue—uninspired, disorganized, mundane dialogue.

Read More

The Light Factory

By Sandy Gingras

I work the night shift at the light factory.

The gears of the conveyor belt slip

silently, and emptiness goes by me

one segment at a time. I have to take

the dark in my gloved hands and make

something of it, then connect it to something else.

Someone further along the line bends

it, I think. Nobody really knows much about

the other guy’s job here. We just do our part.

There are no windows in this factory.

The air is like milk, and they pump in

music that has a beat, so we don’t fall asleep

on the job, but we still do. My mother says

I should get a real job, make something solid

out of my life. “There’s enough light

as there is,” she lectures me. “There’s the sun

and the stars,” she says, as if I don’t know this already.

“What do you DO in there?” she asks. I don’t want

to tell her how much we joke around, tell stories,

talk about men. “I can’t really describe it,”

I tell her. “I do it mostly by feel.” Sometimes,

I bring one of the seconds home

with me after my shift. They don’t like it

when you do this, but everyone sneaks some.

I go home at dawn, put it on my dresser

next to the open window, watch it fan

out like a wild thing into the pink sky.

I don’t know why it feels so good to let it go.

Read More

POOF

By Sandy Gingras

My mother wants her head to be frozen

after she dies. I’m against it, but

there’s no talking to her. She has a brochure.

On the cover, there’s a picture

of a white building with no windows.

I tell her, I go, “I’m never gonna visit you there.”

She says, “Fine, fine,” the way she does.

She reads me the whole brochure.

She’ll be maintained at something-something degrees

until they come up with the technology to defrost

her. The, she says, “POOF. It’ll be like

being microwaved.” I go, “Think about

what happens to popcorn.” She keeps on reading

about how they’ll just fiddle around with her DNA,

and she’ll grow a whole new body. I don’t get that part.

I go, “What if they can’t grow you a body,

and you’re stuck being an alive head forever.”

She says, “Then you’ll have to carry me around.”

I knew it. I knew it.

Read More

The Undersized Negative

By Robert Glick

Selected as winner of the 2014 New Ohio Review Fiction Contest by Aimee Bender

Sometimes the day after Mom’s miscarriage, a chemistry teacher with chin-only stubble interrupts class to tell you he is dying. There were so many reasons not to be anywhere. I, Dr. Watermelon, convened everyone at the abandoned house, which I insisted on calling the sketch house, on account of the Etch A Sketch I had found in a toy chest. My buddy Filbert plopped himself down on one of the oyster chairs; the air clouded with dust mites and dried skin. “Finders, keepers,” he said. We demanded answers of the Harris family from phone bills and colanders, from the oregano scent of the bathroom cleaner, from a postal sack half-full of gas caps. The throat to the fireplace was choked; perhaps a bird’s nest. Rob and Ron each kept one eye perched on the doorless front door, wary of the patriarch Dustin Oskar Harris barging in to reclaim what he once owned. They thought the sketch house itself was sketchy, as if its waxy kitchen linoleum had been responsible for mawing open and swallowing its former occupants. Ron suggested that we get sizzled on the freon from the fridge. Rob agreed; they were repurposers. “Highly toxic,” Filbert said, reluctantly we transitioned to flicking matches at the shelves—flyfishing magazines, nautical books – knowing damp, expecting sulfur, anticipating cartwheels of burn through the air. Filbert, nicknamed for the teratomic testicle lodged like a moon above his kidney, had a talent for fire: me, not so much. I was a Pisces; I went as long as I could underwater.

Filbert’s lit match flew through the air and landed on my crotch. I didn’t want to move. I felt crowned, blinkered by a halo of marsh fog. I observed the flicker of little flame, a prickle of warmth on my jeans. “Huh,” I said. That was my best eloquent admiration for the trajectory of heat and light.

Read More

The Egg

By Eric Nelson

We’re sitting at the table the way people do

When a family member dies and a stream of well-wishers

Arrive with sympathy and food.

Everyone is concerned for the widow, 70, tough, wiry,

Who now seems weak and befuddled, staring at people

She’s known for years without answering,

Rising and walking out the back door, staring at the woods

At the far end of their land.

Returning to the table without a word.

We’re all thinking how often one spouse dies

Soon after the other, dies of nothing

But lack. Because we are surrounded by guns, her husband’s

Sizeable collection—pistols in glass cases, rifles

In racks and corners—talk turns to their value, the merits

Of revolvers versus semi autos, plinking, protection.

Now, for the first time, the widow speaks, remembering

That she went to the coop this morning and found curled

In a nesting box a snake, unhinged mouth filled

With a whole egg, disappearing a swallow at a time.

She walked back to the house, pulled her .410

Off the rack, returned to the coop and blew its head off.

A hog-nose, she says. A good snake. But I had to.

She shrugs her shoulders. I had to. Glancing

At each other, we nod in agreement, relieved.

Read More

Gun on the Table

By Eric Nelson

My favorite scene in Body Heat has nothing

To do with the intricate plot

That William Hurt and Kathleen Turner

Devise to kill her rich, oppressive husband.

My favorite scene, maybe ten seconds long,

Shows Hurt getting into his car as an antique

Convertible drives by, a fully costumed clown

At the wheel, waving. Hurt stares, slightly

Bewildered, while the clown passes and disappears.

That’s it. Cut to Hurt and Turner in another

Sweaty sex scene and post-coital planning,

The foregone noir conclusion closing in. Meanwhile,

Since we know there are no meaningless details

In art, we keep expecting the clown to reappear

Or at least figure indirectly yet clearly in the action.

Like Chekhov said—if there’s a gun on the table

In act one, it had better be fired by act three.

But no, the clown is random, there and gone, an odd,

Unrelated moment like any of the ones that pass us

Every day and we barely notice

Because life isn’t art, isn’t revised for coherence,

Not until our lives collapse around us

Like a circus tent in flames

And we begin to look for the alarm we missed.

Read More

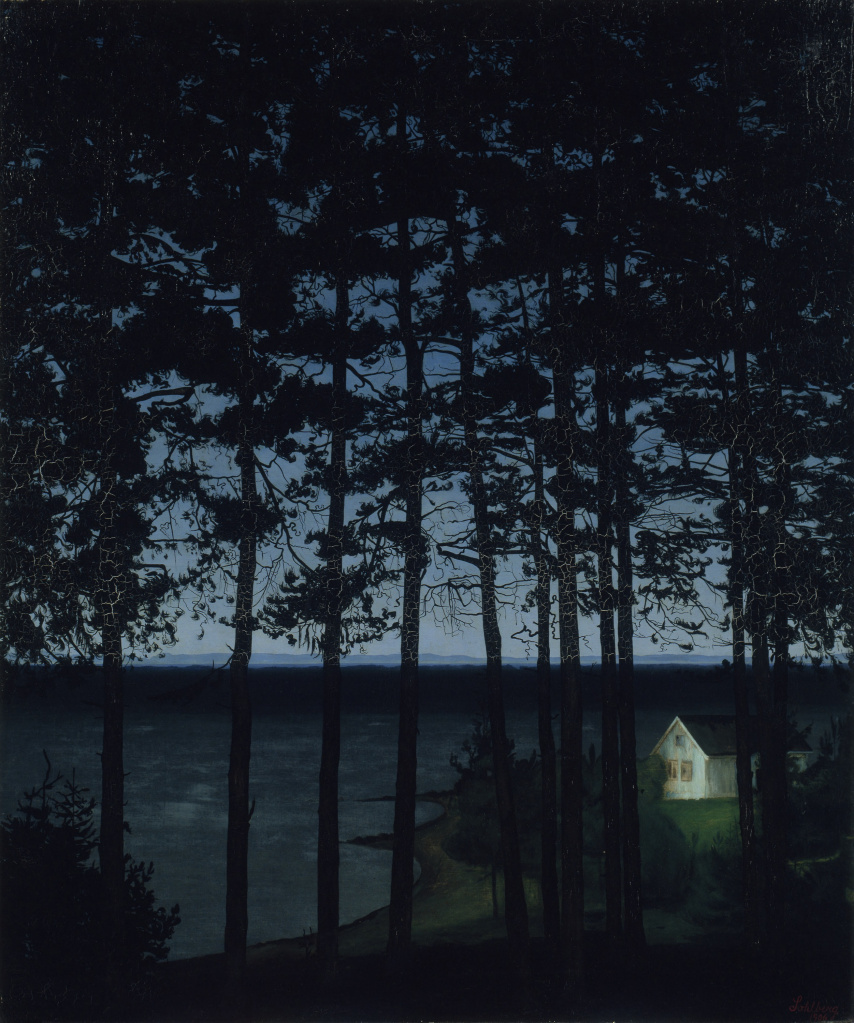

My Life with Pines

By Tom Wayman

1

In the glow of a fluorescent, I sit leaning

over a table to sort through parts of

a jigsaw puzzle, working hard to recreate

a picture displayed

on the box I purchased

while outside

great pines have moved in the darkness

down the ridge to surround my house, many of the trees

taller than the roof. A fierce wind

causes the pine trunks to sway, their limbs

churning the dark in wild

and pitiless gestures.

2

Pines thrive in arid soil, mostly sand,

little else will grow in. These trees regard cedars

who love the damp, who must be surrounded by relatives,

as gloomy, phlegmatic,

timid. Cedars, according to pines, are simple-minded

about safety, suffusing themselves with water

as protection from fire. Cedars might as well be,

pines jeer, a fern. Whereas pines

only reproduce in the heart of a blaze,

their cones needing the insatiable rage of flames

to climax, open, release.

3

No matter how many nights, months, decades

I pore over my jigsaw

the one piece that remains to be found

is a pine.

Read More

Activity Room

By John Bargowski

My mother wants nothing to do with the puzzle

two other residents,

whose wheelchairs have been rolled up

to a folding card table,

are trying to put together—

a west side shot of the New York skyline

broken up into a thousand pieces,

the stubborn morning smog

she could see from the apartment

she had to give up photo-shopped out,

the OT insisting Mom join in the fun,

taking my mother’s stroke-locked hand

and guiding it to

a corner piece that’s an easy fit,

When Time Slows Down

By Lawrence Raab

Now I’m lying in a narrow hospital bed,

waiting for the first tests to come back,

raising the cup of apple juice to my lips,

then setting it back on the table

very carefully. I’ve been watching

a large round clock, so much like

the clocks in the schoolrooms

of childhood, where the big hand clicked

loudly as another minute was forced into place.

Was it fourth grade or fifth?

The Road

By Lee Ann Dalton

I left, not looking back. I was afraid.

I left the things he bought me, just in case.

I had to close my eyes to find the road.

I carried names and numbers, tucked inside

a pocket in my purse, and not much else

to leave and not look back. I was afraid

of corners, entryways, store windows, hid

and dodged whole neighborhoods, memory’s curse.

I had to close my eyes to feel the road.

Nights, phone off, lights on, I stood guard

on the balcony, wrapped in please. Worse

than leaving, is not looking back. I was afraid

he’d come slash my tires, stage his suicide

or mine, since I refused to witness his.

Sometimes I closed my eyes to see the road.

I’m still ashamed to say how much I lied

to make him step away, give me the keys

so I could leave, not look back though I was afraid.

I closed my eyes to walk the open road.

Read More

Intercession

By Jennifer Leonard*

When, years later, I learn Kevin Miller,

the boy who grew up next door, is in jail

for drugs and a stolen car and a gun,

I think of eighth grade:

Kevin with his buck teeth and buzz cut

always getting into fights, Kevin suspended

once for carving the F-word into a church pew

during Wednesday Mass, then again

for slinging walnuts against the windshield

of Mrs. Sabatino’s car.

And that one time, on the field at the end

of the street, where the boys gathered after school

to pick teams, Mark McGarity said,

We don’t want the retard,

meaning my brother—

and Kevin said, What the fuck, man,

and Mark said, Well then prove he can catch a ball,

and when Kevin shrugged and said Fine,

and told my brother to go out for a pass,

and my brother did, but did not catch the ball—

when it bounced twice off the ground,

and my brother looked down at his sneakers,

and Mark told Kevin, Yeah dude, there’s no way,

and all the other boys stood

in a sort of ring, and waited for someone

to hurt someone else—

but instead, Kevin thumped my brother

on the back and said, Let’s go. And my brother—

who may not ever be able to memorize equations

or read, but knows when a man risks himself

for another—

he followed Kevin home to our back yard,

where Kevin threw my brother the football,

and though the ball passed again and again

through my brother’s hands,

Kevin kept throwing, telling my brother

where to move and when, and I can picture, now,

my brother’s face so serious and filled

with concentration—

and Kevin, throwing until their shadows

fell long over the yard.

Read More

Pavlov’s Dog

By Derek JG Williams

I chase my shadow all morning. The neighbors watch

from between drawn curtains.

I tear up clumps of lawn until my blood churns how it does

when the bell rings. I sit in the sun and pant.

Next time I’ll lunge for his throat. But the bell sounds

and I love him still. When I run away, it’s to nowhere

special. There’s a certain slant of moon

I seek. It changes the angle of my longing.

Hunger is the pain I can’t be free of—when I’m sitting

in the sun I love him.

I’m never free. I’ll lunge for his throat. The neighbors will say

I told you so.

Read More

Photograph Albums

By George Kalogeris

“We finally got all of our family photos

Onto our home computer,” Quentin was saying,

Just as we entered the Asian fusion place.

And that’s when it hit me: all those leather albums

With their matted pages and bristly hides,

In their mundane way as archly ceremonial

As the Golden Dragon preening against

The restaurant window. All those cumbersome tomes,

In a decade or so defunct as the dinosaur.

But once their images have all been scanned,

Why should it matter? By then the cherished snapshots

Will have all gone into the world of light—

Or at least into cyberspace. Ancestral faces

That once unfurled from trays of salty water

As dark as Lethe, and then were pinned on strings,

Ex-voto like, and left to dry, will seem

A little less spooky-stern without the shades

Of their twentieth century negatives to haunt us.

And pantheons of illumination so vast

They promised we’d see ourselves reflected in

Their image forever—Olympus, Polaroid, Kodak—

Will shrink to the candle-watt stature of household gods:

Preservers of birthday parties and graduations,

Penátes of pointed hats and obnoxious horns.

For My 1st Ex-Lover to Die

By Francesca Bell

I heard this morning my old lover died, and I cannot say I loved him, though I may have said it at the time, cannot say he was a good person or lover or anything other than a man who called me in the small hours, driving back roads drunk in his Ferrari, when I was 23 and he was 50, who bought me books and a Lalique clock that’s been broken 20 years, who was the dumbest smart person I ever knew, crying in his car at 4 in the morning, wearing a coyote skin coat that reached to his shoes, and I didn’t want his money or his cocaine or to be his 7th wife, and I’ve seldom thought of him except to remember a dark animal crossing his driveway at night, and the 2 staircases in his grand house, going up, going down, and how I held him, deep in my body, and he made a small, sad sound.

Read More

Dialing The Dead

By Mark Kraushaar

I’d never call.

First of all, I’d be intruding, and besides

I can see my dead friend with all his dead friends

even now, translucent, weightless, winging

through a cloud or sitting in a circle

on some creaky, folding chairs—

Hello, my name is Peter and I’ve

been dead ten years, car wreck.

Hello my name is Edith and I’ve

been dead a week, pneumonia.

Hello, my name is Frank and I’ve been . . . .

Oh, I know they’d all be friendly but even

dialing later when I guess he’d be alone

I’d have too many questions:

If you’re nowhere now and nothing

is this the same as everywhere and everything?

And, Peter, do you sleep in heaven?

Do you eat up there?

What’s the weather anyway?

And that tenderness of heart we try so hard

to keep a secret: in heaven we’re

wide open, aren’t we?

Stay in touch.

No, don’t.

Read More

Last Call

By Penny Zang

Each night, after work, we changed our names. We were trying on new identities, seeing which ones fit. Serena and I would throw off our aprons and get undressed in the car, wiggling into tight black pants and shirts thin as napkins. Sometimes we wore red lipstick, sometimes eye glitter. Then we’d find a new bar with the same tattered barstools we were used to balancing on, the same veil of smoke and low light that felt like home. To the men who approached us, we turned into different girls, ones who knew how to charm even without the promise of making a tip.

Our new names were decided on the spot, never the same name twice. They were names we’d once used for our baby dolls, names we’d wished our moms had given us: Isabel, Deanna, Lily. Everything else came later—our stories, our new personalities—fueled by beer and tequila, a practiced game of improvisation. Sometimes men invited us home or out to their car. Sometimes the night just fizzled and we’d stumble out to the street in the wrong direction, too lost to even know it. We’d stop to eat greasy pizza and compare notes, our throbbing feet the only part of us that wanted to give up.

Read More

Sitting in a Simulated Living Space at the Seattle Ikea

By Abby E. Murray

Finalist, New Ohio Review Poetry Contest

To sit in a simulated living space at Ikea

is to know what sand knows

as it rests inside the oyster.

This is how you might arrange your life

if you were to start from scratch:

a newer, better version of yourself applied

coat by coat, beginning with lamplight

from the simulated living room.

The man who lives here has never killed.

There is no American camouflage drying

over the backs of his kitchen chairs,

no battle studies on the coffee table.

He travels without a weapon,

hangs photographs of the Taj Mahal,

the Eiffel Tower above the sofa.

The woman who lives here has no need

for prescriptions or self-help:

her mirror cabinet holds a pump

for lotion and a rose-colored water glass,

her nightstand is stacked with hardcovers

on Swedish architecture. The cat who lives here

has been declawed, the dog rehomed.

There are no parking tickets in the breadbox,

no parakeets shrilling over newspaper

in the decorative cage by the desk.

When you finish your dollar coffee

and exit through the simulated front door,

join other shoppers with chapsticks

in their purses and Kleenex and receipts,

with T-shirts that say Florida Keys 2003

and unopened Nicorette blisters in their pockets,

you will wish you could say this place

is not enough for you, that you are better off

in the harsh light of the parking garage,

a light that shows your skin beneath your skin,

the color of your past self,

pale in places, flushed in others.

Read More

The Game

By Steven Cramer

Let me clarify some things about the game.

First rule: think about the game, you’ve lost.

No tiles, cards, currency, whirling dials: all pieces

are included, space has been cleared at the table.

Join in. Your turn. Kids learn the game in school

corridors, score it in red along their forearms,

new staves on old. It doesn’t end when the day ends:

race for the stairs, dodging the geeks and slow kids,

thunder of fists on lockers, last push to the streets.

The old hands they become play all night, by daylight

a winner still in doubt. Friction Ridge, Lake of Enclosure,

Dot and Spur: its variants can wear a pencil to its nub.

Wedded to the game, couples bop to the Heart-Flip,

the Mind-Winder, later to lie on sheets deliberately

left blank. Who invented the game? Who made up

the jokes passed from laugh to laugh? Black suit

for weddings, same for the funeral. In between, quick

as a nail sparks an Ohio Blue Tip, it fixes in its sights

the boy who puffs, walks; leaves in a down of frost

crushed beneath his feet. At the ridge he’ll climb,

sun warms the girl expecting him, curve of her hand

moist to take him. When he comes, the game beats

in his heartbeat thumped by the wallop of her heart

beating against his; and like a spider tumor, spins

webs in his brain, in love now with how it’s played.

Read More

A Theory of Violence

By Jennifer Perrine

Selected as runner-up of the 2014 New Ohio Review Poetry Contest by Alan Shapiro

In the museum of sex, the video loops

its cycle of common bonobo behavior:

penis fencing, genital rubbing, whole groups

engaged in frenzied pairs, their grinds and shrieks

playing for the edification of each patron

passing through the room. We all summon

our best poker faces. One woman speaks

softly, reads from the sign that describes

all the various partner combinations,

the multitude of positions, how relations

lower aggression, increase bonding within tribes.

We linger over this way of making peace,

wonder to each other if we would cease

our litany of guns, bombs, missile strikes

if we spent more time in wild embrace.

The exhibit doesn’t mention our other cousins,

chimpanzees, who form border patrols, chase

strangers in their midst, leave mangled bodies as lessons.

That’s the story we already know

and want to forget through the release

of these erotic halls, where we seek the thrill, the bliss

of these animals who hold us captive

while we lament what traits we’ve found adaptive.

Read More

Embarrassment: from baraço (halter)

By Jennifer Perrine

Selected as runner-up for the 2014 New Ohio Review Poetry Contest by Alan Shapiro

All he found when he came looking for us was the home my mother wanted to leave behind: newspapers stacked knee-deep in the hallways, every corner redolent of cat piss, linoleum caked with dried mud and dust, tangles of hair matted to the tub, dried scabs of meals coating plates and bowls piled high in the sink, on counters. Everywhere: the stink, the rot and mold, the great heaps of unwashed clothes, all the filth my mother never let anyone see. No friends allowed inside. Even her dates didn’t get in the door. She spent her nights at their dubious dens, leaving me alone to toss hamburger wrappers and soda cups on the living room floor, our one trashcan so full I couldn’t empty it. My father, finding all this mess, assumed the worst, took photos, jotted notes, thinking the house had been ransacked, that we’d been robbed, killed or kidnapped, though police assured him there were no signs of struggle. How she’d let the house go, he couldn’t imagine. Before the divorce, I heard her shout: I’m no one’s maid. Years later, when my father asks how we lived in such squalor, I tell him I never noticed at the time, though once I did: My best friend, Heather, and I were playing outside when a sudden shower drove us to huddle under the eaves. Soaked, I took pity, opened the door, disobeying my mother’s one rule. Inside, Heather didn’t ask questions about the mildew, the crumpled paper bags she had to brush aside to sit. She refused the towel I handed her to undo the work of the rain. I saw it then: tatty, gray, stained. Heather left, and later, when my mother found the couch still wet, I told the truth. Her face flushed; I tried to bolt. She reined me in with one hand, unfastened her belt. If they see this, they’ll take you from me, she screamed through the volley of blows. My back grew a rope of welts. They’ll call me unfit. Is that what you want? I tell my father none of this, judge it best not to show him the last bits of how his ex fell apart once they were unhitched. I don’t say how I, too, was the mess, tether she yearned to slip, so she could careen unimpeded through life, how I held tight as she zoomed away, raced toward a place where she’d be no one’s mother, no one’s wife.

Read More

Envy

By Patricia Horvath

The sign on the door says: Children Under 18 Not Admitted to the Chemotherapy Suite Under Any Circumstances.

They call it a suite, this room at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital where chemotherapy is administered, as though its occupants were members of some elite group, which in a sense I suppose they are. For reasons that elude me, the chemotherapy suite is located on the same floor as maternity services, and the elevator is often crowded with an odd mix of cancer patients and pregnant women. The cancer patients are generally hairless, elderly, their skin ashy, their bones prominent. The pregnant women are all flesh and smiles.

On Jeff’s first day of chemo, three months earlier, a couple made out during the entire ride to the eleventh floor. Teenagers practically, they wore tight jeans, cropped vinyl jackets. Her back hard against the elevator rail, her distended belly pressed into her partner. They made little moaning noises as they kissed. I tried to give Jeff my “What the fuck is this?” look, but he was too preoccupied—or maybe too polite—to notice. The other passengers looked away. I watched them not watching and then I stared at the floor.

Read More

Seafood

By Amanda Williamsen

Baltimore, Maryland

My uncle calls from the wharf; his freighter is in;

he’s walked to the nearest food and I find him

in a crab shack at a table by the window.

Waitresses carry crabs on trays, whole piles of them—

stiff, blue, dead—and the restaurant patter crackles

with the brittle speech of small mallets on their shells.

Elena, his wife—she’s from Colombia, my age—

wants a divorce. She’s living in Miami

with some Cuban, he says; she’s got his TV and his car.

When his crabs come, I order grilled cheese,

tell him about karma, how I’ve removed myself

from the chain of suffering and he says, shit,

picks up a crab and whacks it squarely on the back.

He tells me about winters on Superior, ice boats

cracking a path through December until the solid freeze

of January, how he shoveled iron ore from the hold

until the red dust rose in clouds from his clothing,

rinsed from his body in the shower like a gallon of blood;

and before that, how he went to Vietnam while my father

went to college, how he bombed the jungle beneath him

without ever looking down while my father dropped

out of college without ever looking ahead;

and before that, before the war, how the two of them

hit a tree one night while driving on River Road.

You’d have thought we wanted to be that tree, he says.

It broke the car, broke seven of his ribs, nearly broke

my father’s heart but in the end it just broke his spleen

and ripped him open from shoulder to hip.

My great aunt—the whole family tells the story now—

came from Kansas and prayed him back from the dead.