By Jeffrey Harrison

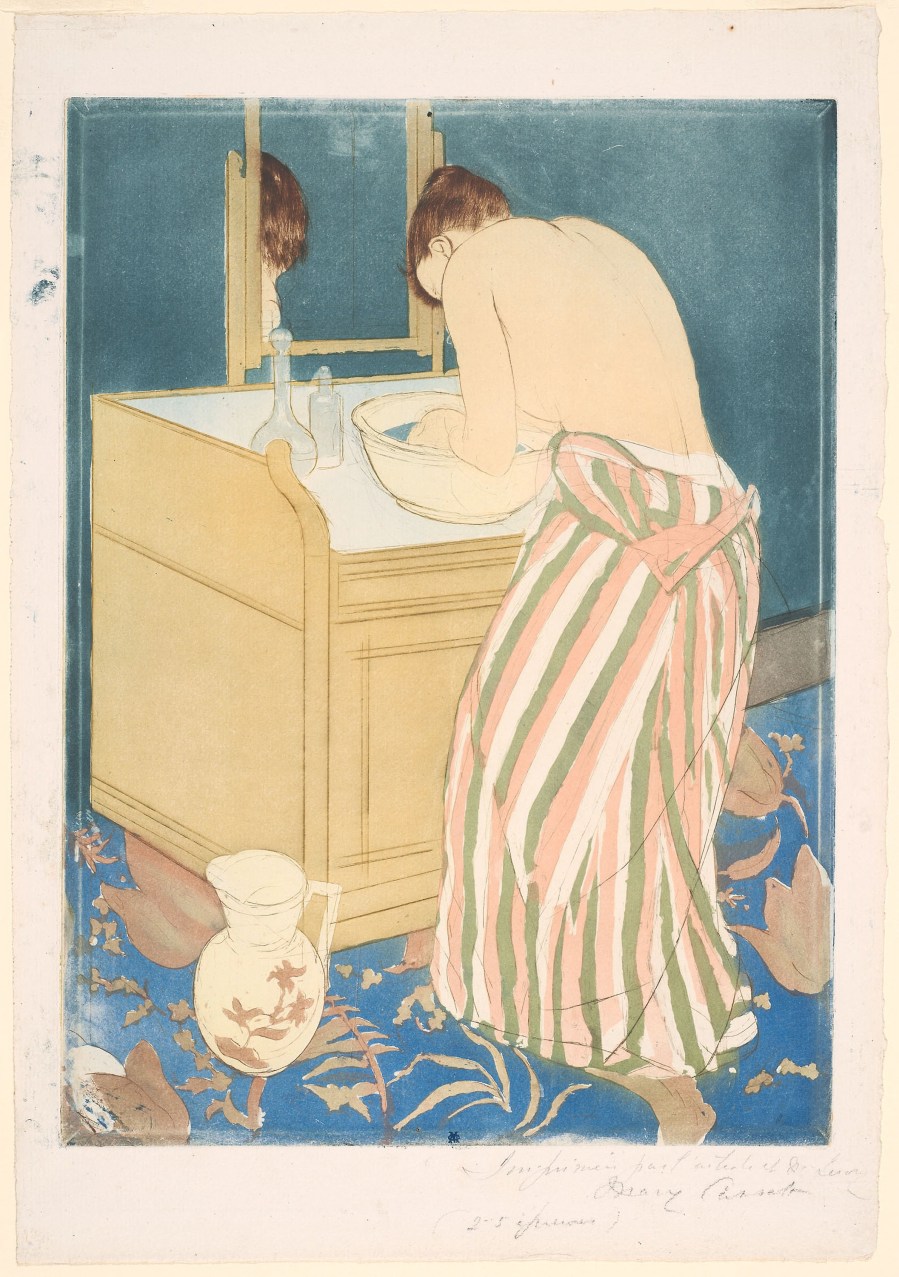

Featured Art: Le Code Noir by Pierre Prault

I unearth it while cleaning up my office,

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing

that my father sent me two years before he died,

its bright red cover like an accusation,

a yellow Post-it bearing his cheerful

half-script still attached: “Jeff—even if you read

only the first part of this book, you’ll get the gist.

Return it some time, no hurry. Love, Dad.”

I chose to place the emphasis on “no hurry”

and hadn’t cracked its little crimson spine

when, a year later, he asked me what I thought.

When I told him I hadn’t gotten to it yet,

he said he wanted it back, so he could lend it

“to someone who might actually read it.”

“But I might still read it,” I said half-heartedly.

“No, you won’t.” Which made me all the more

determined not to read it, so I said fine,

I’d send it back. But I never did—and then

he got sick, and our investment

in that particular contest seemed pointless.

But here it is again, this little red book

so unlike Mao’s, as if my father were making

a move from beyond the grave. Okay, my turn.

Is it because I need to prove him wrong

even now, or that I want to make amends

belatedly for disappointing him yet again

that I open the book and begin reading?

Or am I doing it in his honor? And is he

still trying to tell me I invested

in the wrong things?—poetry, for instance.

“Counting angels on a pin,” he said once.

Which is just the kind of cliché I find in the book.

Later, though, he claimed to like my poems,

the funny ones at least. And if we drew a graph

of our relationship over his last decades

it would look a lot like the Dow: a steady ascent

with several harrowing jagged downward spikes.

The little red book says nothing about those,

though it does advise not getting too caught up

in the market’s dramatic nose-dives.

Unless, perhaps, you’re trying to realize

your loss—another topic that the book,

with its rosy perspective, blithely avoids

as it enthuses on “the miracle of compounding.”

But instead of getting annoyed I feel an odd

joy: my father could have written this book.

He too was an optimist who liked to talk

about money, and so I used to ask him questions—

What’s the best kind of mortgage to get? Is life

insurance a good idea?—and those led

to some of our least fraught conversations.

That’s why he gave me the book. And he

was right: I get the gist after two chapters.

And the suggestions seem helpful, if limited—

I even underline a few sentences.

Still, that other book, the one about losses,

would be more complicated, and harder to write,

its author finally coming to understand

that, no matter what the future brings,

he won’t be able to ask his father’s advice.

Read More