Europeans Wrapping Knickknacks

By David Kirby

Featured Art: by Gustave Caillebotte

They’re so meticulous, aren’t they? They take such care

that I am ashamed for my country, that impatient farm boy,

that factory hand with the sausage fingers. First there’s

the fragile object itself—vase, jewel, ornament—then tissue,

stiff paper, bubble wrap, tissue again, tape, a beautiful bag

made from something more like gift wrap than the stern brown

stuff we use here in the States, then the actual carry bag

that has a little string handle but which is, in many ways,

the loveliest part of the package except for the object

you can barely remember, it’s been so long since

you’ve seen it. In America, we just drop your trinket

in a sack and hand it to you. Oh, that’s right. We have cars

in this country: whereas Stefano or Nathalie has to elbow his

or her way down a crowded street and take the bus or subway,

you get in the car, put the bag on the seat next to you,

and off you go, back to your bungalow in Centralia or Eau Claire.

Of course, this doesn’t mean you’re culturally inferior

to Jacques or Magdalena just because, as Henry James

said in his book-length essay on Hawthorne, we have no sovereign

in our country, no court, no aristocracy, no high church,

no palaces or castles or manors, no thatched cottages,

no ivied ruins. No, we just do things differently here:

whereas Pedro and Ilsa take the tram or trolley,

you have your car, and now you’re on your way home

to Sheboygan or Dearborn, probably daydreaming

as you turn the wheel, no more aware of your surroundings

than 53-year-old Michael Stepien was in 2006 when

he was walking home after work in Pittsburgh, which

is when a teenager robbed him and shot him in the head,

and as Mr. Stepien lay dying, his family decided

“to accept the inevitable,” said his daughter Jeni,

and donate his heart to one Arthur Thomas

of Lawrenceville, NJ, who was within days of dying.

That’s one thing you can say about life in the U.S.:

we have great medicine. Mr. Thomas recovered nicely

after the transplant, and he and the Stepiens

kept in touch, swapping holiday cards and flowers

on birthdays. And then Jeni Stepien gets engaged to be

married and then thinks, Who will walk me down the aisle?

No cathedrals in America, says Henry James,

no abbeys, no little Norman churches, no Oxford nor Eton

nor Harrow, no sporting class, no Epsom nor Ascot.

My Father Visits Not Long After My Mother (His Wife Twenty Years Ago) Dies

By Brock Guthrie

Featured Art: by Paul Gavarni

My father’s in town for a quick couple days

and it’s early morning and not much to do

and he needs some smokes and I need

a few things from Lowe’s. We walk to my car

and he says, “Man, you need a car wash,”

and I say, “Yeah, I’ve just been so busy,”

which isn’t really untrue, but I tell him

there’s a place on the way. We get in my car

and he says, “Go to McDonald’s, I’ll buy,”

and we wait in the drive-thru and he says,

“You need a vacuum too,” and I don’t reply

because the food is ready. I pass him his

Egg McMuffin and drive down the road,

carefully unwrapping my breakfast burrito,

and this commercial I’ve heard a dozen times

comes on the radio, some guy with a nasally

New York accent, but only now do I gather

it’s an advertisement for snoring remedies.

My father says, “If there are two vacuum hoses,

I can do one side and you can do the other.”

We drive past strip malls. I wave vaguely

toward a Mexican restaurant I kind of like

but I can’t think of what I want to say about it,

so I kind of mumble and my father does too

except his is more reply, like, “Is that right?”

The car wash kiosk has eight confusing options.

The Uber Diaries

By Kyle Minor

Indianapolis, Indiana. Somewhere near Keystone Avenue and 62nd Street my iPhone pings. A college student from Hyderabad, India. He is pleased when I tell him he’s my first customer. He tips me two dollars.

*

I pick up my second customer in front of a bar in Broad Ripple. He gets in the front seat. His hair is grown to thigh length, and he is on some kind of party drug that makes him want to touch things.

“Please stop rubbing my arm,” I say.

He apologizes.

Near Rocky Ripple, he takes off his shoes and socks and rubs his bare feet

on the windshield.

His feet leave little rabbit marks. He is a large man with very tiny feet. When

I drop him off at the donut shop, he doesn’t leave a tip.

*

Read More

Leaf Blower

By Alan Shapiro

Featured Art: The Poet’s Garden by Vincent van Gogh

Swept up so suddenly in parabolic

spasms like a starling flock

or curtain swelling, billowing out

while all along the edges

this or that leaf frays

from the pack the force

keeps driving forward

over the courtyard bricks—

while in ear muffs and face

mask he points the havoc

this way and that as if

to see what happens because

he’s in no hurry, he’s peaceful,

calm, Laplace’s Demon

out for a stroll, cool source

of all that whirling, lost in

contemplation of the incalculable

force of every movement from

the greatest body to the smallest

atom, holding it all in mind—

working it out, in ear muffs

and face mask following behind

what whirls before him, fleeing,

which is why he strolls.

Read More

Hole in One

By Alan Shapiro

Since my dad was blind by then,

when David and I led him from his apartment

to the tee of the shrunken one hole

golf course that served as kitschy

courtyard for the complex

of retirees only well-off

enough for this unironic

aping of the rich, it was by habit

only that he looked down

at the ball he couldn’t see,

then up and out into the void

of stunted fairway and green

while first this foot then that

foot patted the fake grass, almost

kneading it cat-like till the tight

swing arced the ball up high

as the second-story windows

and I swear it was like a trick

ball the pin on an invisible line

reeled in straight down

into the hole—his first and only

hole in one, on the last swing

of a club he ever took, though

we didn’t know this then, and how

we whooped my brother and I

as we jumped and capered throwing

the other balls up into the air

while the old man baffled said what?

what happened? what? already wistful

for this best moment of a life it was

his luck the blindness made him miss.

And now it’s my luck, isn’t it just

my luck, to be the last one

remembering, as if I’m not just

there with them but also far

removed above it all and watching

as through the block glass of an upper-story

window high enough for the ruckus

not to reach me but too low

not to see the filmy blur of

bodies hugging one another

pumping fists as arm in arm

the three of them head out across

the fake grass of that single hole.

Read More

Closer

By Alan Shapiro

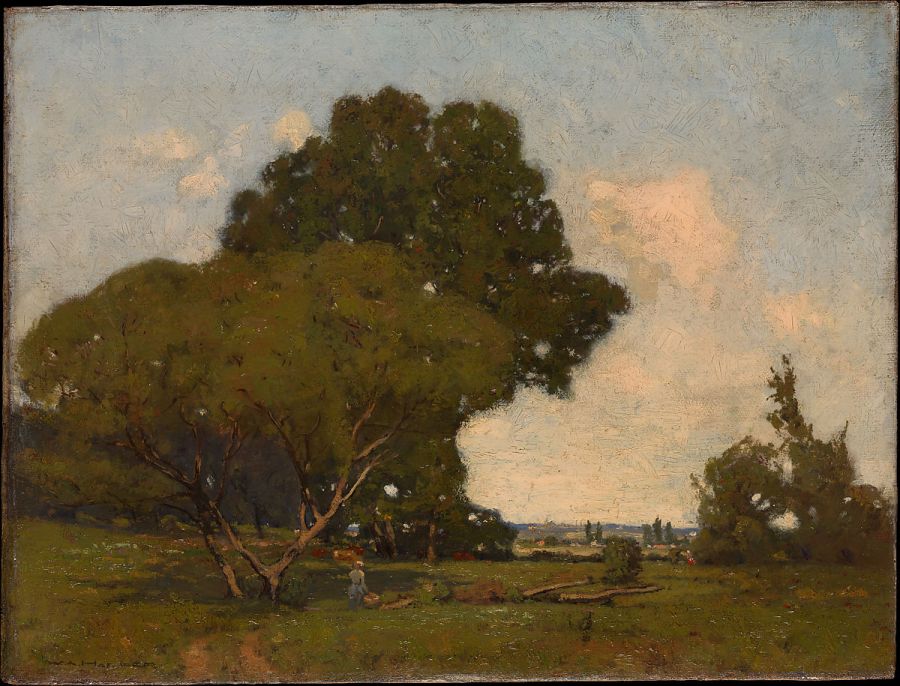

Featured Art: by William A. Harper

How the great closer—when the batter lunged

and swung through the curve for strike three—

turned his back to the plate as if there were no batter,

and his one concession to the moment

(that there even was a moment) was

to hitch one shoulder as if to shrug off

a slight annoyance while his face unbothered

by expression measured its mastery by what

it wouldn’t feel, or show, was like and not like us,

our faces, lips, how, when I tried to kiss yours,

they shut tight against what up to then, it seemed,

they’d opened to so eagerly I never thought

they ever wouldn’t or imagined you might ever

turn away not just as if I wasn’t there but

never had been. And weren’t we, maybe, like

the batter too, and not, the way he flipped the bat and

caught it and as he strolled back to the dugout,

holding the bat up, seemed to study it

with such rabbinical amazement

you could almost think he’d failed on purpose

so he could finally see within the bat

whatever lack the bat, not knowing it was lacking,

had hidden in the grain to show him now.

Read More

Bay Sunday

By W.J. Herbert

Featured Art: Boys in a Dory by Winslow Homer

1.

Wind hits the cliff face and climbs the palisade

as three men at a slatted table play cards.

Two wear hats. A third faces the sun and smokes.

All three are gray-haired, but none is my father.

He wouldn’t have played without scotch

on a Sunday or sat on a park bench, anyway.

2.

A man holding a child speaks to her in Mandarin

as he touches a small seat attached to the back of a bike.

He pats handlebars and points to spokes, saying bike

every twenty words or so, then taps the front wheel gently,

the way you would touch the shoulder of an old friend.

3.

Some Sundays even if I’m not near the bay,

I imagine my father playing solitaire at a slatted table

as I lean over the cliff rail, watching waves

that grapple with the beach as they leave it.

On the bike path below, grit spins under a stream of cyclists

as a man wipes a child’s tear with the edge

of his sleeve and speaks to her in a language so soft and low

the bay curves like an ear to hear it.

Read More

Stateline Lake

By Arlyce Menzies

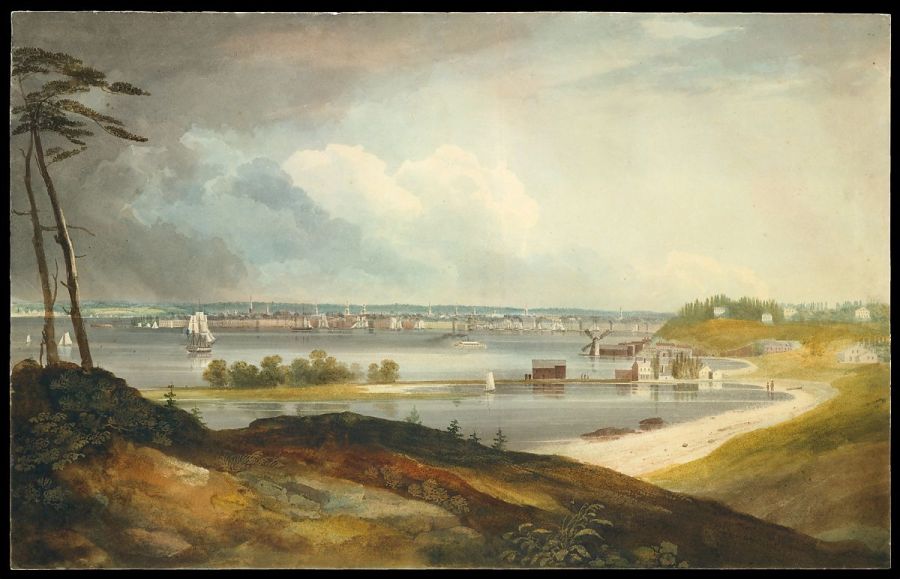

Featured Art: by William Guy Wall

Slipping through the shadow of trees

at dusk to the old strip mine, we took off

our clothes under the wide catalpa’s

strung slender pods. The lake

shone with the last evening light,

cicadas casting their long call over the water.

We both dove and you didn’t come up

for a while. Then, you broke out, fist first,

and shouted for me to come look.

I sheared the dim surface with dark strokes

and found you gripping a watersnake

that curled and whipped your wrist.

You were delighted, and I tried to imagine

the impulse, impossible for me, that made you

grab the slither against your ribs

underwater. And the jolt you rose with,

the triumph of your quick hands,

and the body with which you felt the world.

Read More

Real Things

By Nicole Hebdon

Lorna tells her fiancé that we met in the cemetery. “Chloe was writing a paper on the War of 1812 graves,” she says. “And I was taking photos for my photography class. It’s a haunted site. Paranormal investigators have looked into it and everything.” This is partially true.

The Riverside Cemetery is known for disappearing children and hovering orbs, but I wasn’t writing a paper. I was writing an article for the supernatural edition of the school magazine.

And we didn’t meet there.

Lorna’s fiancé, Caleb, tells us how he and Lorna met, and she folds her hands in her lap, like a child at Sunday school. Whenever one of Lorna’s roommates stands to get a wine cooler, or giggles purposelessly, he starts his sentence over, so I’ve heard his story approximately three-and-a-half times when he finally lets someone else talk.

They met in high school. They met in high school. They met in high school. They met . . . Lorna and I met at an abandoned mini-golf course. The castle’s peak looked like a crumbling monument, and I was sure it would lead me to another gravesite for my article, but past the thick cattails, there were toppled bridges, a sputtering stream that emptied into a square-shaped pond and Lorna wearing a university T-shirt.

Read More

The Petrified Man

By Pamela Davis

Featured Art: by William Trost Richards

It’s dead August, a go nowhere night, and I take

Mom’s Chevy Monza, pick up a girlfriend,

head down to the Nu-Pike amusement park

at the shore. We’re sixteen and sunburnt,

peasant blouses, short-shorts, ready.

Dad taught me to swim in the park’s domed pool,

ankles glitter-kicking past mosaic tile,

but only the Cyclone Racer’s left now,

a tattoo booth, dime-toss swindles, some freak shows.

Mary Lee says the senior boys hang out by the roller coaster

and heads that way. A hand holds me back by the arm,

hoarse voice coaxes

Hey girlie, wanna see a man hard as a rock?

Shoved from behind—I stumble—almost fall

onto a body, ageless, naked, diapered like a baby

on a table. It’s airless as a crypt. His face narrow.

Is he real? The barker’s dank breath, a nudge

toward the table,

Touch him.

I reach my finger to the dry, shinydrab thigh.

Nothing moves but a black electric clock jerking

second-to-second, hands vacuuming time

from the room. The carny demands a dollar, I pull

a crumpled one from my pocket,

back out like a low-slung cat.

The Bearded Woman leans

against a wall, cigarillo loose

on her bottom lip. She spits,

Look, it’s the girl who touched the Petrified Man.

I’m sixteen, sunburned, picking my way

along the gritty beach, screams falling

from the shuddering coaster. The moon

stares me down, the sand swallows

my steps, and the tide rushes forward,

slick with neon.

Read More

Ode on a Midlife VW

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by Edouard Baldus

—After Matthew Dickman

Parked next to its German cousins,

the van’s a message to the office bourgeoisie:

Hey look, not me. I’ve got a 4-cylinder pop-top

escape pod back to 1983 with a picnic table in back,

motherfuckers. I could be a tortoise, tent in shell,

ambling away from a mortgage.

The kind of tortoise that shows up in Tallahassee

after ten years of grazing on roadside dandelions.

Driving home, I keep an eye out for Gandalf

like maybe he’ll have his thumb out at the city limit sign.

If I saw him I would stop like it’s no big deal

and tell him to throw his staff in back.

I need to believe there’s still time for me

to take a bro trip in a van with a wizard.

No questing anymore. No destination.

Mount Doom’s done its thing. Sauron’s dead.

Just a sort-of-old guy and a wizard in a VW van,

sharing a bag of Cheetos and a Dos Equis six-pack.

Maybe we’d drive back East where

things are still green this time of year.

It could be a little like rewinding time,

headlights unwinding the two lanes up ahead,

“The Grey One” pointing out a barn owl

flashing through the highbeams.

Maybe after three beers and a full moon

I’d finally see the really big picture—

how we’re all just hydrogen

squashed into other stuff by stars.

It could be the KLUV-in-the-desert-

Jesus-is-your-friend-drive-until-dawn road trip.

All my life I’ve tied my ties,

polished my shoes, said my vows,

then let my people down.

But Gandalf doesn’t care. The road trip

would be all honesty and wonder:

The you’ve-made-your-bed-and-slept-in-it-for-too-long-

now-drive-away-with-it-in-a-van road trip.

Road trip of acceptance. My arches

have collapsed and occasionally I shave my ears.

Who cares? No one’s coming to rescue us

because we’re way past rescuing. I loved you.

I hurt you. I changed the tire and drove away

in a VW van. And maybe just before dawn,

the wizard would elbow me and point with a shrug

to a Waffle House like why the hell not?

Inside, the night-shift waitress would be taking off

her apron and moving to a window

to watch the sun come up.

Maybe she’d call me Love and serve me bad coffee

in a chipped mug. Maybe her name would be Grace.

And maybe she’d pull off her hairnet and take out

the bobby pins one by one, shaking her head,

letting her long hair down at last.

Read More

Interstate 5 Ode

By Craig van Rooyen

To adopt a highway, say

between Kettleman City and Coalinga,

you don’t need to love

the shorn stockyards or the Holsteins

drowsing in the haze of their own stink. But it helps.

You don’t have to sing

to the rows of uprooted almond trees

next to the angry sign about the “Dust Bowl”

Congress has created.

You don’t even have to believe

“Jesus Saves.”

To adopt a highway, you need

only walk its shoulder, bending from time

to time for a plastic lid

skewered by its straw, a pair

of pantyhose with reinforced toes

and a crotch thicket of goat head thorns.

When you come upon

a ruptured suitcase at the center of its galaxy

of intimates sprayed across two lanes,

look both ways before stepping

onto the scarred asphalt to harvest

the cloth pieces, worn soft on a stranger’s skin.

To adopt a highway, say

between Avenal and Chowchilla,

you don’t have to listen for the inmates

on their side of the gun towers or

even remember their names, the ones

whose sins you spoke aloud to cover your own.

If you walk the shoulder long enough,

stepping over roadkill gore and

tire carcasses, your face may dry up

and Haggard may rise from the heat shimmer

to sing his creosote songs; and still

you need not let the lonely in.

But it helps. To adopt

a highway you must walk

through the fumes of a spent afternoon

looking for its leavings. And if you’re lucky

a red-tail will swoop ahead of you in the dusk,

a hawk-flame lighting post after post.

Read More

Ode to My Backyard Gopher

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by Thomas Cole

Oh blind digger, furred borer,

miner of nothing at the end of a tunnel

to nowhere. My nocturnal brother,

I can report up top

the screech owl sounds like

he’s ripping holes in a paper sky.

Tonight’s scent salad:

honeysuckle-jasmine served under

a thin glaze of starlight. Nothing

between me and Venus

but goosebumps. What gets you

through the long hours down there?

Now and then when I go inside

to pour coffee or smash graham crackers

in warm milk, I read a few lines

of William Carlos Williams

who can get high on open scissors, or

a waste of cinders sloping down

to the railroad. I’m looking

for things to tie myself to. Maybe

the chain-link backstop that, right now,

is making diamonds of the backlit clouds,

or the trembling peppercorn tree.

Anything to stay topsoil-side

for a few more decades. Do you fear

the sky as much as I fear the press of earth?

Do you stay awake imagining

the unbearable lightness of air?

The imagination, intoxicated by prohibitions,

rises to drunken heights, says Williams,

and I walk outside again. Everywhere

new leaves, so thin the moon

shines through. My neighbors cling

to each other in their sleep.

A three-legged stray totters out from shadow

to beg with a lopsided wag. Dig

oh warm-blooded rodent.

Bore your tunnels though no one sees

their dark patterns. Come morning,

the three-legged dog will hobble

from fresh mound to fresh mound,

quivering at the scent of your passage.

Read More

Costco Ode

By Craig van Rooyen

Featured Art: by Joachim Beuckelaer

—After Marie Howe’s “The Star Market”

And they did all eat,

and were filled: and they took

up the fragments that remained,

twelve baskets full.

—Matthew 14:20

Today, my people—the people Jesus loves—

are shopping at Costco.

Membership checked, we’ve entered

the light-drenched Kingdom of More.

We’re sampling Finger Lake

Champaign Cheddar morsels nested

in tiny paper cups. We’re watching golden

chicken carcasses ride a Ferris wheel to nowhere.

Our carts are full to overflowing

with applesauce squeezes and shrink-wrapped

Siamese twin Nutella jars. Take. Eat.

Take some more. But it’s not enough.

Here you can buy a theme park

for your master bath, on credit.

You can buy buckets of pain

killers, boxed sets of princesses, a

Rebel 4-Pack of Star Wars Bobbleheads.

The crushed-ice battlements of the seafood kiosk

frame Wild Cooked Red King Crab Legs so big

it looks as if a dragon has been dismembered

by retirees in hairnets and aprons.

Though abundance assumes satisfaction,

maybe this is a place of famine.

But why shouldn’t a miracle happen

at Costco? Up the frozen-food aisle now

comes a woman on her electric “Amigo Value Shopper”

with a cow-catcher-sized basket up front and

an orange safety flag in back.

Weanie Tender, PO

By Jennifer Christman

Like the dry, hot winds of Santa Ana itself, the sound came in waves. Pop-pop- pop-pop-pop. Weanie Tender didn’t know from where. Weanie Tender didn’t know from what. Staccato bursts of varying lengths and speed, then brief respites. Now, however, is a different story. There’s a constant vibrato. Take any moment—take this moment—Weanie can hear it, by God. Pop-pop-pop-pop- pop. He can feel it. He need only focus his mind to detect what’s on the order of a cosmic palpitation. Pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. Weanie is a low-level PO. He wants to be a detective someday.

“Force’s under attack,” says his partner, Dom, wolfing Chick-n-Minis from his own private 20-tray, steaming up the cruiser. Bag-of-bones Weanie is crumpled in the passenger seat.

“You hear it now?” says Weanie, drawing in a sharp, short breath.

He and Dom are on break outside the Chick-fil-A on Bristol. Weanie can’t sit still lately. He jiggles his legs and wrings his hands, listening, deeply, to what he’s now thinking must be an engine running—that’s it, an engine running rough, like an outboard motor, and snappy, pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. But that would require a boat, and water. And the city, the entire county, is landlocked. And the seismic index is low. Weanie checks daily.

Read More

Naked, Fierce, Yelling Stone Age Grannies

By Lisa Bellamy

Featured Art: by Evelyn De Morgan

I shudder when I think of the giant beavers—

tiny-brained, squinting Pleistocene thugs—

they bared rotting incisors longer than a human arm,

they infested ponds and rivers, smothered

gasping sh with their acid-spiked, toxic urine,

they slapped their murderous tails—bleating,

they dragged themselves up the riverbank,

spied sweetgrass; they charged the crawling babies,

the tiny baby bones, trampling, they didn’t care—

hurray for the naked, fierce, yelling Stone Age grannies—

they dropped their hammer stones, they grabbed

sharp sticks. Who can forget their skinny, bouncing breasts?

They beat the giant beavers, they speared; they smeared

hot, thick beaver blood over each other’s faces,

their bony, serviceable buttocks—who can forget the grannies—

Read More

Our Fathers

By Lisa Bellamy

Our fathers never spoke to us of their wars.

Each morning, they girded their loins with tool belt

and slide rule, according to their appointed trades.

In the summer, as they backed out

our driveways, we ran after them. In the winter,

they left, whistling, as we slept.

They created Japanese–style goldfish ponds,

built backyard gazebos, sang barbershop harmony

and strummed the ukulele, but they refused

to call themselves makers of beauty.

They woke us at midnight to see

the Aurora Borealis, carried us out

to the rose and white light-waves streaming,

named for the goddess of dawn who brings life,

and the god of the north wind who brings death.

Our fathers grew restless. They started to pace,

walked outside to gawk at the stars.

When we asked, Can we come, they said, No.

When we asked Why, they said, Hush.

Our fathers stopped kissing our mothers.

They came home midday: red, laid-off, warned

for swearing at the foreman, said they were sick

unto death. They slammed screen doors, bedroom doors,

storage shed doors. They started to drink. They stood up

from couches, pushed dogs that nosed them, stumbled

outside, yodeling. Said they felt bigger

than the sky. They drank in bomb shelters,

at the Legion Post, watching TV. They drank

driving us to Scouts, bottles between their knees.

They drank when we begged them not to and when

we tried to ignore them. Sometimes

they slammed us against walls, sometimes

said they were sorry. One by one, they left:

in their sedans, vans, the pick-up, walking to the bus stop.

They left in the morning as we sat, silent,

at the kitchen table, eating cereal before school.

We watched them leave with their suitcases.

They left a goodbye note for us to find

after track practice. They left at night after fights.

Some stayed, but stopped talking, or faded

fast, eyes rolled back, clutching their heart.

Others left over time, from their wasting diseases.

They said they would never forget us.

Our fathers said they loved us, and we believed them.

Read More

Moo

By Chrys Tobey

Featured Art: by Vincent van Gogh

Woman is not yet capable of friendship: women

are still cats and birds. Or, at best, cows.

—Nietzsche

Love, I’m sorry for the time we were walking home with groceries in our

arms—you carried the chicken and potatoes and I held the chocolate. As we

laughed about something I can’t remember, our dog barked

at someone, and I just bolted, ran off. Also, love, there were all

those mornings you’d wrap your arm around me—your hand

spread across my spotted stomach. Good morning, you’d whisper

and I’d reply, Moo. I’m sorry for that. I also hope you’ll one day

forgive me for the time you were weeping, your mom had just died,

and I charged as though you were red. Love, I regret

all the evenings I’d drive home from work and open the door to smell

roasting squash and garlic. We’d sit at our tiny kitchen table, and you’d

say I love you, but then I’d regurgitate the ratatouille. I’m sorry about that, too.

Love, I apologize for my aversion to leather and how we’d snuggle on

the sofa, my nose in your neck, but then you’d cry, Ah, my back

because unfortunately, I weighed 1,000 pounds. And Love, what remorse

I have for leaving you, for wandering away to graze in another pasture.

Read More

Cockadoodledoo

By Chrys Tobey

Our parson to the old women’s faces

That are cold and folded, like plucked dead hens’ arses.

—Ted Hughes

An old woman thought her face was a dead

hen’s arse. Maybe it was all the years

of plucking and waxing. The woman had no idea

what would make her think her face

was a dead hen’s arse and not a live hen’s

arse, and why the arse and not the beak, but

she did. It couldn’t be my age, the woman thought.

It couldn’t be the men, not when everyone knows men

love older women, especially much older, especially

with all the grandma porn, all the old women sex

costumes, all the men who ogle elderly women in walkers.

She had read so many books where men longed

for older women, where old women seduced helpless

wide-eyed men. She saw billboards where old women

modeled teenage clothing, modeled Brazilian

bathing suit bottoms. And she knew the trend: folding

wrinkles into one’s face using a Dumpling Dough Press.

People would stop her and take selfies. You look

like a movie star, they’d say. They wouldn’t leave her alone.

She’d shrug. Maybe it was the way she’d sometimes cluck

when she made love to her husband? This could be the reason

he’d whisper, One day I may trade you in for an older model.

Or maybe it was all the eggs she ate. Or her penchant for feathers.

Or how her mother used to call her my little chickadee. The woman

was unsure why she thought her face was a dead fowl’s

feces-extruding cloaca. She only knew she was tired

of seeing twenty-year-old men with women who could

be their grandmothers, old women who treated the men

like so many dimpled birds.

Read More

Coach O

By Robert Hinderliter

Featured Art: by Owen Jones

Coach Oberman watched from his office window as a group of students prepared the bonfire by the south end zone. Two kids stacked tinder while another knelt beside a papier-mâché buffalo they would throw on the fire at the end of the pep rally. Oberman couldn’t wait to watch it burn.

He’d just gotten off the phone with Mike Treadwell—coach of the Ashland Buffaloes—who’d called to wish him luck in tomorrow’s game. Mike had been Oberman’s assistant for three years before taking the job at Ashland High. And now, after back-to-back state titles in his first two years, he’d been offered the defensive coordinator position at Emporia State University. This would be the last time they’d face off.

“I’ll miss seeing you across the field,” Mike had said. “Although I sure won’t miss trying to stop that Oberman offense.”

This was pandering bullshit. In their two head-to-head contests, Mike’s Buffaloes had routed Oberman’s Hornets by at least four touchdowns.

“I just wanted to say thanks,” Mike had said. “I couldn’t have gotten this far without you.”

He’d said it like he meant it, with no hint of sarcasm, but Oberman knew there was venom behind those words. In Mike’s two years as assistant, Oberman had treated him badly. Mike had a good mind for the game, there was no denying that, but he was a scrawny wuss with thick glasses and a girlish laugh. He didn’t belong on a football field. Oberman had banished him to working with the punter and made him the butt of jokes in front of the players. When Mike’s brother-in-law became superintendent at Ashland and handed Mike the coaching job, Oberman had scoffed. And now Mike was moving on to a Division II college while he was stuck muddling through another losing season with an eight-man team in Haskerville. He knew the irony wasn’t lost on either of them.

Read More

Women in Treatment

By Theresa Burns

Featured Art by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Why had I not noticed them

before? The women in treatment

on every block, it seems, leaving

the library, walking their dogs.

Once they hid themselves

beneath wigs, fashionable hats

in the city, or entered softly

in Birkenstocks and baseball caps,

stayed out of the way. Now they

show up, unannounced.

In offices, in waiting rooms,

in aisle seats with legs outstretched,

the women in treatment

flip the pages, reach the end,

bald, emboldened. One

outside a florist today arranges

lantana in time for evening

rush. A bright silk scarf

around her pale round head

calls attention to her Supermoon.

And one woman my own age,

in my own town, takes up a table

right in front. She nurses a chai latte

in a purple jacket, her hair

making its gentle comeback.

What she pens in a small

leather notebook: a grocery list?

Ode to her half-finished

French toast? The kind of poem

living people write.

Read More

My Babysitter Karen B Who Was Sent to Willard Asylum

Winner, New Ohio Review Poetry Contest

selected by Kevin Prufer

By Jessica Cuello

There are only two photos of me as a child.

She took them, she had no child.

She had Kool Cigarettes and a job at the drugstore.

She gave me the Crayola box with the built-in sharpener.

Four hundred suitcases were stored in the attic

of Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane.

She joined her twin brother there.

She wore her black hair down.

A child could admire it.

She bought me an Easter basket,

a stuffed rabbit whose fur rubbed off.

She walked everywhere.

She painted circles of blush on her cheeks.

Loony, people said so,

I mean grown-ups who saw signs

who passed her on our street before she

started to call and say Remember,

on the phone she said Remember,

Remember the date we killed her brother,

forgetting he’d been committed.

I took her hand and tagged along like an animal.

She was perfect to a child.

Calculations

By Linda Hillringhouse

Featured Art: by Julia Margaret Cameron

We’re waiting for our copying jobs

at Staples, so she starts chatting me up,

says she’s a retired math teacher.

When I tell her I taught English,

she says that English teachers

are the worst and she always kept

her mouth shut at the book club

because they always wanted

evidence and she just wanted

to talk, have a cup of tea,

what’s the big deal?

And I’m being too nice as usual

making it clear to her I’m not

one of those book bitches.

Now I’m hearing about the math museum

in New York and I can tell she wants someone

to go with. I’m brainstorming excuses

but it’s my turn to say something so I say

how much I like zeros and that I even

tried to read a book about them.

Now she’s telling me how she used to prove

to her students that she can get 2 to equal 1

and keeps saying, Let A=B and it’s like

God’s saying it, but now she’s saying, Anything

can be anything and this is starting to sound

like patent bullshit and she’s droning on

and I’m so glazed out I can only nod and say hmmm

like I’m Bertrand Russell finally grasping the true nature

of mathematics when all she wants is some tea and company

and it’s her bad luck that it had to be me she ran into,

the Queen of Zero.

Read More

An Education

By Molly Minturn

Featured Art: Still Life with Cake by Raphaelle Peale

It was spring and I walked

the streets in the late afternoon

with the best poet I knew.

She was tall with a severe face

like an early New Englander.

Her ancestors survived genocide.

We didn’t discuss our work, only

the weather, how the blossoms

were upsetting. The war was on.

We bought a hefty slice of cake

and walked slowly under a murder

of crows back to my apartment.

This seemed too evocative,

almost to the point of embarrassment.

The cake was coconut. We split

the slice, sitting at the small

table in my living room, away

from the sun. At the time,

it was the present. Here

in the future, I sometimes forget

to breathe, waiting

for the next catastrophe. That cake

was pure in its sweetness, the poet

alive with me, her eyes scanning

my face, both of our histories

neatly bound in our throats.

I wanted to ask if she was frightened

by living, by the change

in the light. Instead, she slid the plate

across to me, a Ouija planchette,

insisting I take the last bite.

Read More

Here Comes Happy

By Shauna Mackay

So, as I understand it, none of your children have died?

They die all the time, she says. Over and over.

The doctor, young as ever-dying sons, suggests a short course of medication and refers her to someone who might help her to change her thoughts.

On the way home her walk’s different: rocking, dodgy. This is how the embarrassed go. Shanks’s pony won’t trot nice: one two, onetwo, no, one, two, for God’s sake. She keeps a Bonaparte hand to pat the phone in the pocket of her shirt, there, there; can’t let it lie at the bottom of her bag, roofed over by crap and the birthday card for Lance. Her middle lad hasn’t answered the text she sent from the doctor’s reception area: he’s got an away game today, rugby, that bloody rugby; he must be injured, quadriplegic, on a ventilator, brain dead. How can she go on? She smoothes out the prescription in her hand, crosses the road to the chemist.

A text comes as she waits for the tablets to be dispensed. Her son is fine, all good, they won. She pictures him downing celebration pints, shots, being a daft sod, succumbing to fatal blood alcohol levels. She makes the pharmacist bide there for payment, stood like a plum, while she texts back. Well done son but mind you go canny x. As soon as the first text has gone she sends another to say on the coach journey home he should sit in a middle aisle seat opposite the driver’s side for she’s heard it’s the safest place in the event of a crash.

Read More

Wex in Totus Taggle

By Owen Doyle

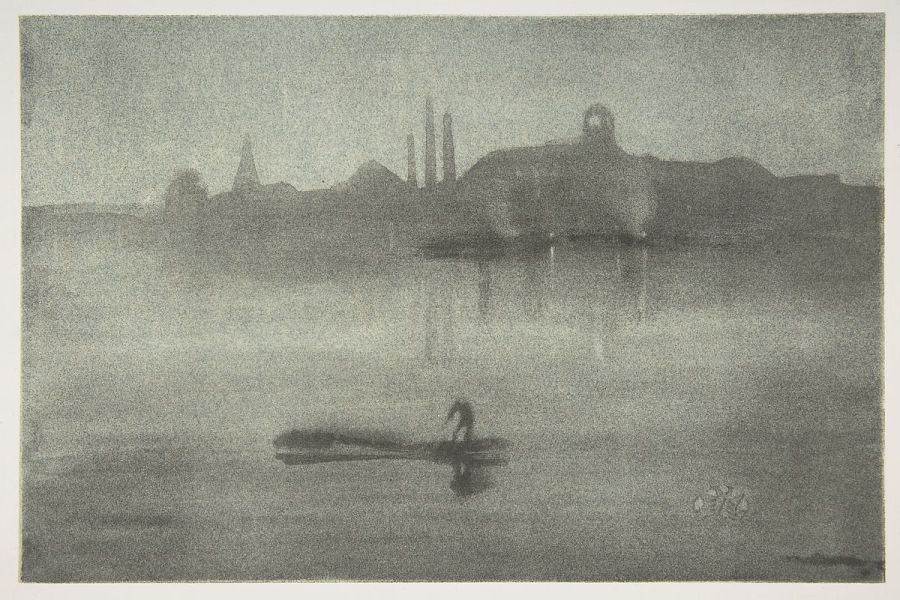

Featured Art by James McNeill Whistler

Words in an old notebook

prove (I was twenty-ish, then)

that mind-mud and dismally

tangled brain material

have causes other than old age

or illness. At the time,

they might have been explained

by the rum or beer in mind-

blowing excess the night before.

I don’t remember.

But surely those episodes

of binge and babble

are far outnumbered

by drier spells of helplessness:

me, frozen

over the neat rectangular form

of a blank page, compelled

to write totus to avoid

writing nothing.

It’s reason enough for terror

or self-pity, the thought

that those very things—the booze-

blasts and blackouts—were then

and are now the efficient

cause of wex and taggle:

furrows of gray matter, tilled

for art and wisdom, laid

waste, and the flood of those young

insults cascading still. But no,

I’ve heard that it’s very common:

this empty gaze, the pen loose

between a finger and a thumb,

its tip hovering

over absolutely nothing. And so,

as tragic as it all may be, finally,

I won’t let it bother me too

too much. Why taggle over wex

totus? I’ll pour myself a glass

of wine and see

what comes spilling out.

Read More

At the Wives’ Coffee

By Abby E. Murray

Featured Art: A Rose by Thomas Anshutz

You should know

there is no coffee

at the Wives’ Coffee

There’s prosciutto

and cream puffs

and conversation starters

printed on glossy paper

And here’s a tip

from the commander’s wife:

Wives who forget

to wear the crest pin

will be fined a dollar

because these pins

aren’t free ladies

and immediately

I’m a stump

rolled into the river

before a flood

I am uncooperative

a hollow log sheltering rebel fish

a disruption of roots

But the conversation starters

are required and my question is

What discussion topic bores you to sleep every time?

Read More

Language Immersion

By Jeff Walker

Featured Art: by Martin Johnson Heade

Nobody, speaking of fluency, would remember

that party where I told the young woman

seated on the floor: this food tastes good. Nothing untoward.

She surprised me by crawling on all fours, her blouse fairly open

at the top by way of happy gravity, to gently

take the food from my hand with her teeth; alarmed me

because I was not young and

what could she be thinking by doing that?

Around us on sofas and out under the trees hummed

the language I would not understand after years of trying

and also of trying to understand why I couldn’t,

an easy-to-employ tongue with few options and simple

structure but when they speak to each other it’s unintelligible,

a giggle-babble, a bubbly stream of what I guess are words,

vain emptying of thought from one head to another,

like all language, really.

Why not give it up and run silent miles

through the mud and rice paddies with my jogging buddies,

or ride miles on a motorbike alongside a mute, jiggling citizenry,

my face contained and content behind its polycarbonate shield,

my mouth behind its filter mask, and who on the back

not speaking, only chewing?

Read More

Return

Winner, New Ohio Review Fiction Contest

selected by Mary Gaitskill

By Analía Villagra

He was gone for eleven years, and Jackie is still getting used to the idea that Victor is out. Exonerated. His release had warranted a few sentences on the local NPR station, so Jackie knows that he has been at his mother’s place, three blocks away, for a week. She has not yet run into him on the street. Each time she leaves her apartment she scans the sidewalks, and when he does not materialize she feels equal parts relief and disappointment. Thursday afternoon she goes out of her way to walk past his building, willing him to be on the front steps or looking out the window. She slows down. Would he even recognize her now? Her hair is short, with a few stray glints of gray, no longer halfway to her waist and shimmering black. Her eyes have shadows beneath them. Her hips have spread. She’s thirty years old, in good shape she thinks, unless you’ve spent a decade fantasizing about a nineteen-year-old body. Jackie blushes. This is the first time she’s admitted to herself that she wondered—hoped? assumed?—that Victor thought about her while he was away. Eleven years. Maybe he’ll recognize her, maybe he won’t. She can’t decide which is worse, so she stares down at the sidewalk and hurries past the building.

She goes to the Y to pick her daughter up from camp. Graciela is running around the outdoor play area with a group of other kids, their hair wild, their clothes and faces filthy.

“Mama!” Grace shrieks when she sees her.

Jackie waves. She locates the teenagers wearing staff T-shirts, and they hand her the sign-out sheet without pausing their conversation. Jackie half-listens to the latest counselor drama while Grace gathers her things.

Read More

The Blackbird Whistling

By Linda Bamber

Featured Art: by John Frederick Kensett

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

—Wallace Stevens

1. The Beauty of Innuendoes

Meaning in poems comes and goes

like a car speeding down a tree-lined road

sun-shade-sun-shade-sun-shade . . .

Poems’ secret places:

fleeting, hidden, close.

Closer yet I approach you, Whitman warmly says;

and then,

We understand, then, do we not?—never saying

what it is

we understand. As I understand a poem

by my friend

but mustn’t tell him

what about the poem makes me feel so

not alone.

2. The Beauty of Inflections

Yesterday I called my friend.

He was in a peaceful mood

(which he would be the first to say is kind of rare).

As if bubbles of CO2 some clams or scallops had exhaled

were calmly rising

in a steady/wavering

surface-seeking

kind of way

up through his contentment

effortlessly rose some words of praise for me. Plain

and unadorned; clear; direct.

The blackbird whistling,

you might say.

In fact,

if my friends didn’t tell me plainly that they

love me

sometimes,

I wouldn’t understand a single thing

I try to read at all.

Read More

Trees in March

By Linda Bamber

We were seated near the back of the Chinese restaurant, and waiters were

rushing in and out of the swinging doors to the kitchen. At the time we had

not as yet so much as brushed shoulders. Resting on the formica table top, my

hand began to feel odd. Not bad-odd; but most unusual. Trees in early March,

aroused, their branches slightly reddened by the slightly stronger sun, may feel

something similar. They have a new sense of their importance in the scheme of

things; they remember (if I may say so) they are divine. He was looking at my

face, not my hand, so I don’t know how my hand, resting near the remains of

the General Gau’s chicken, intuited its sudden access of significance; but it did.

It had aura you could cut with a knife.

Shortly thereafter he took my hand.

Read More

Mango Languages

By Linda Bamber

Featured Art: by Winslow Homer

—For Chris Bullock (in memoriam) and Carolyn Bernstein

In that world people are not discussing The End of the American Experiment.

Yo soy de los Estados Unidos. ¿De dónde es usted?

(I am from the United States. Where are you from?)

In that world people are not in a rage at their relatives for voting wrong and

sticking to it.

¡Tu hermano se parece más a tu abuelito que a ti!

(Your brother looks more like your grandpa than you!)

People there are not tortured by thoughts of what they should have done to

prevent this; they do not endlessly analyze the causes of the disaster; or notice

how many of their friends are independently coming up with the metaphor of

a tsunami wiping away what is precious from the past and has been defended

by their devoted work.

No llame a la policía. No es una emergencia.

(Do not call the police. It’s not an emergency.)

In that world they do not sit glumly when friends excitedly tell of recent

protest marches; they are not thinking, “Great, feel inspired; meanwhile,

they’ve got all three branches of government.”

¡Me encantaría que me dejaras accompañarte a la esta de Pablo!

(I would love it if you would let me accompany you to Pablo’s party!)

People there are not suddenly crossing the border into Canada in the snow

with children in their arms; or trooping out of Jewish Community Centers on

a Tuesday because of death threats; or writing emergency numbers on their

children’s forearms in indelible ink in case Mamacita doesn’t come home from

work that day.

Every morning I cross the border into Mango Languages, my ticket to

oblivion. “Loading your adventure,” says my computer when I boot it up.

Every ten minutes a woman’s joyful voice says, “Isn’t this easy?” to encourage

me, and I admit I feel encouraged.

Córtalos en pedacitos y échalos al agua que está hirviendo.

(Cut them in little pieces and throw them in boiling water.)

They are speaking of nothing more precious than carrots and onions; not,

for example, the Constitution or the Bill of Rights. We are learning to use the

imperative mood, that’s all; and today we are making soup.

Read More

Near the Campo Aponal, on My Father’s Birthday

By David Brendan Hopes

Featured Art: A Rocky Coast by William Trost Richards

De Sandro’s café with the orange tablecloths

wades into the one stone street

without tourists, all the Venetians pushing

their big delivery carts at first of morning.

From what I understand of it,

the shouting is voluble,

happy, glad to be alive, almost never

without reference to anatomy.

Nine years after your death it is still your birthday.

I’m treating you to cappuccino and showing off

my lacework of Italian.

Ecco, I cry, pointing to the beautiful faces,

the beautiful things.

Everything was outlandish to you. Nothing is to me.

In that way balance is achieved across the long years.

But I think you would like these people.

They would pull out the orange chairs, sit down,

listen to what you have to say. You would be old

and wise in a city old and wise, and that would be

enough.

I’d better think of something else before the mood

turns heavy and hard to carry over the Rialto Bridge

with the shops just opening.

All those selfie-taking children,

all that brightness bearing down.

Happy birthday, I want to say,

from the last place on earth, where the earth dissolves

and the crazy towers lean out over

watching for what comes—sinuous, flowing,

unexpected—next.

Read More

Of Seeing, the Unseen, and the Unseeable: Technology, Poetry, and “When It Rains in Gaza”

by: Philip Metres

1. I Tap My Cell to See

In the beginning, I did not see but heard: news over the radio about the bombing of Gaza in 2014, triggered by a whole series of events—we say “triggered,” as if history itself were a weapon ready to be fired. Voices untranslated, the tone of panic rising, sometimes breaking into anguished cries, the wail of air raid sirens, and the smooth voiceover of journalists, trying to tuck the adrenaline beneath the language, trying to strike a tone that seems fair and balanced.

On Language, Bombs, and Other Things That Exist

by: Kimberly Grey

As poets, we often assemble language to disassemble meaning—or we disassemble language to assemble meaning—and this is all an effort to translate the ordinary (a pair of socks, the name of that place, subway car, chair versus shadow, the front of a sparrow, something afloat like a naked rock) into an extraordinary textual or speech act. The result, we hope, is something new and transformative.

The Technology of the American Sonnet

by: Brian Brodeur

If a poem, as William Carlos Williams claimed, is a machine made out of words, the sonnet can be viewed as a particularly compressed, dynamic, and efficient little gizmo, one that poets have been tinkering with since the 12th century. These tinkerers, of course, have included some of the most foundational poets of Western literature—from Dante and Petrarch through Hopkins and Frost—all of whom have used one variation or another to perform what Phillis Levin classifies as “a mode of introspection, a crystallization of the process of thought.”

The Transitional Voice: Exploring Susan Blackwell Ramsey’s “Ode to Texting”

by: Claire Bateman

There are currently three kinds of human in the world: the non-digital; digital natives; and adapters who have learned to communicate digitally but still remember an analog society though they cannot fully access that prior consciousness, just as no adult can fully access their sense of self prior to their awareness of death and sex. Susan Blackwell Ramsey’s “Ode to Texting” speaks in the voice of the third kind of human, a member of this historically unique transitional species, embodying a before-and-after in our culture in which babies swipe insouciantly on screens almost before they can sit up on their own. Interestingly, rather than relegating texting to the status of object, Ramsey personifies it as a shapeshifting subject she addresses in order to explore the range and complexity of an adapter’s experience. Consider how she opens the poem:

Machines, Mortality, and the Lyric Poem

by: Bethany Schultz Hurst

After my mother died, I kept reaching for my phone. I’d talked to her almost daily during the last years of her illness, when she’d been mostly housebound, watching Hallmark movies and BBC mysteries alongside my patient father and an ever-present small plate of toast she couldn’t bring herself to eat. Because I couldn’t reach her now, I found myself instead playing the matching game I’d downloaded in case I needed to occupy my young son on the flight back to Denver for the funeral. For brief periods, the game let me put my grief in the background and focus on the simple task of matching little clusters of fruit or flowers to earn points toward restoring a cartoon estate garden that had fallen into disrepair. The game offered order and arrangement, a small sense of accomplishment when other tasks (or even former pleasures, like reading) seemed to demand too much concentration.

Of the People, for the People, by the Robots

by Christopher A. Sims

American fiction has its small share of memorable politician characters—Willie Stark in Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men and Robert Leffingwell in Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent to name a pair—but there’s a strand of this tradition that is becoming more relevant in 2016: Artificial Intelligence politician figures in the work of two of our most prominent science-fiction writers, Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick.

Take Me to Your Lady Leader

by Kristen Lillvis

Contact, Carl Sagan’s best-selling 1985 science-fiction novel, tells of alien shape-shifters, wormhole-traveling spacecraft, and—perhaps the most fantastical element of the bunch—a female president. Yet Contact’s protagonist, Eleanor “Ellie” Arroway, compares President Lasker to her predecessors with no acknowledgment of their gender difference, noting that Ms. President demonstrates an appreciation for science seen in “few previous American leaders since James Madison and John Quincy Adams.” Despite her tie to the presidential establishment—and regardless of Sagan’s attempt to make her gender unremarkable—President Lasker still fulfills the function particular to women world leaders in literature. Whether she erodes or extends existing gender stereotypes, the female president operates as a sign of the apocalypse or, at least, a harbinger of the unfamiliar, a reminder to readers that they have entered a world drastically different from their own.

"This Time I'm Going to Fool Somebody": Willie Stark and the Politics of Humiliation

by Dustin Faulstick

“Folks,” roars Willie Stark on the eve of his impeachment trial, “there’s going to be a leetle mite of trouble back in town. Between me and that Legislature-ful of hyena-headed, feist-faced, belly-dragging sons of slack-gutted she-wolves. If you know what I mean. Well, I been looking at them and their kind so long, I just figured I’d take me a little trip and see what human folks looked like in the face before I clean forgot. Well, you all look human. More or less. And sensible. In spite of what they’re saying back in that Legislature and getting paid five dollars a day of your tax money for saying it. They’re saying you didn’t have bat sense or goose gumption when you cast your sacred ballot to elect me Governor of this state.” From his colloquial diction and insults to his collegial banter with his own supporters, from his invocation of corruptly used tax money to his reference to the sacredness of the ballot, Stark identifies himself as one of the people. Before neurosurgeon Ben Carson or business moguls Carly Fiorina and Donald Trump, farm-boy-turned-lawyer Willie Stark was the ultimate political outsider.

Villainous Villanelle

by: Denise Duhamel

My id spits and licks his lips, trips my conscience,

my ego, Miss Goody Two Shoes.

Her neon pink laces make him nauseous.

On Being Asked to Contribute to the Villains Feature

by: Richard Cecil

I searched ten years of word files

looking for titles with names of politicians who

enrich the rich while trampling down the poor

and corporate criminal CEOs who screw

employees out of wages, rape the Earth,

and hide their stolen billions far offshore,

and drew a blank. I also found a dearth

of killer clowns and warlords steeped in gore,

religious rabble rousers, nasty nuns,

child-abusing Catholic priests—zero.

No bought congressmen who vote pro-gun;

no homicidal patriotic heroes.

What’s blinded me to monsters all those years?

The Frankenstein inside. It’s him I fear.

Read More

Designs Less Palpable: Emotional Manipulation and Even-Handedness in Keats

by: Matthew VanWinkle

In a February 3, 1818 letter to his friend Reynolds, Keats rejects a reading experience that he associates primarily with Wordsworth: “We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us—and if we do not agree, seems to put its hand in its breeches pocket.” The reproach is so scathing because it acutely observes how rapidly the poetry’s interest in its audience cools, from the importunate heat of the design to the indifferent withdrawal to the pocket. Keats is fuming primarily at Wordsworth’s dogmatism and propensity for self-congratulation, as we hear earlier in the letter, where Keats complains of being “bullied into a certain Philosophy engendered in the whims of an Egotist.”

Yeats and Heaney: The Poetry Without the Pity

by: C.L. Dallat

When W.B. Yeats dismissed Wilfred Owen’s World War I poetry as “all blood, dirt & sucked sugar stick” (and omitted Owen, Sassoon, and Rosenberg from his 1936 anthology), he was making a powerful statement, not just about distaste for sentimental language and the role of pity in poetry, but about the poet’s duties and limits. He had already excluded writing war poetry from his own list of obligations in 1915’s “On Being Asked for a War Poem,” but only later became more coherent on the abjuration of pity as an unfit subject.

Tell It Cool: On Writing with Restraint

By: Debra Marquart

For years, I’ve encouraged students to “tell it cool” when narrating a tale that is harrowing or emotional. A cool narrator can be a buoy in rough waters. I’ve always thought this advice came from Hemingway, but at this moment as I search my bookshelves for the place where Hemingway said it, I can’t put my finger on the quote. I know it’s in there somewhere, likely in one of the letters (bossy letters full of unsolicited advice and signed “Papa” when friends were just writing to ask for money).

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway famously wrote about knowing what to leave out. In his discussion of the short story, “Out of Season,” for example, he remarks that he left out a key event connected to the real story: “I had omitted the real end of it which was that the old man hanged himself.” According to a letter that Hemingway wrote to F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1925, the story was “an almost literal transcription” of an experience he’d had while traveling in Europe with his first wife, Hadley.

Read MoreI Second That Emotion

by: Rebecca McClanahan

A few years ago, I attended a literary gathering and heard four poets and memoirists read from their work. They were all accomplished writers, varied enough in their approaches to evoke laughter, sighs, nods of acknowledgment, a collective gasp at one point, and, toward the end of the evening, some tears as well. Tears are not uncommon at readings, of course—I have cried at several—but in this case the tears came not from audience members but rather from one of the readers, who had warned us that she might “choke up” because of the emotional content of the autobiographical piece she was about to read. Her introduction, followed by a tearful presentation, suggested either that the work was too new to share publicly or that she had planned her reaction and was intentionally manipulating us. As she spoke, I sensed listeners growing more and more uncomfortable, as I was. Some leaned back into their chairs, some crossed their arms. The more emotional the reader’s performance became, the less effect it seemed to have, an unfortunate outcome, especially given that the work was potentially moving in and of itself. But it was as if the writer did not trust the work, or perhaps did not trust us to do our job as listeners: to bring our own emotional response to the work.