The Dans

By Molly Reid

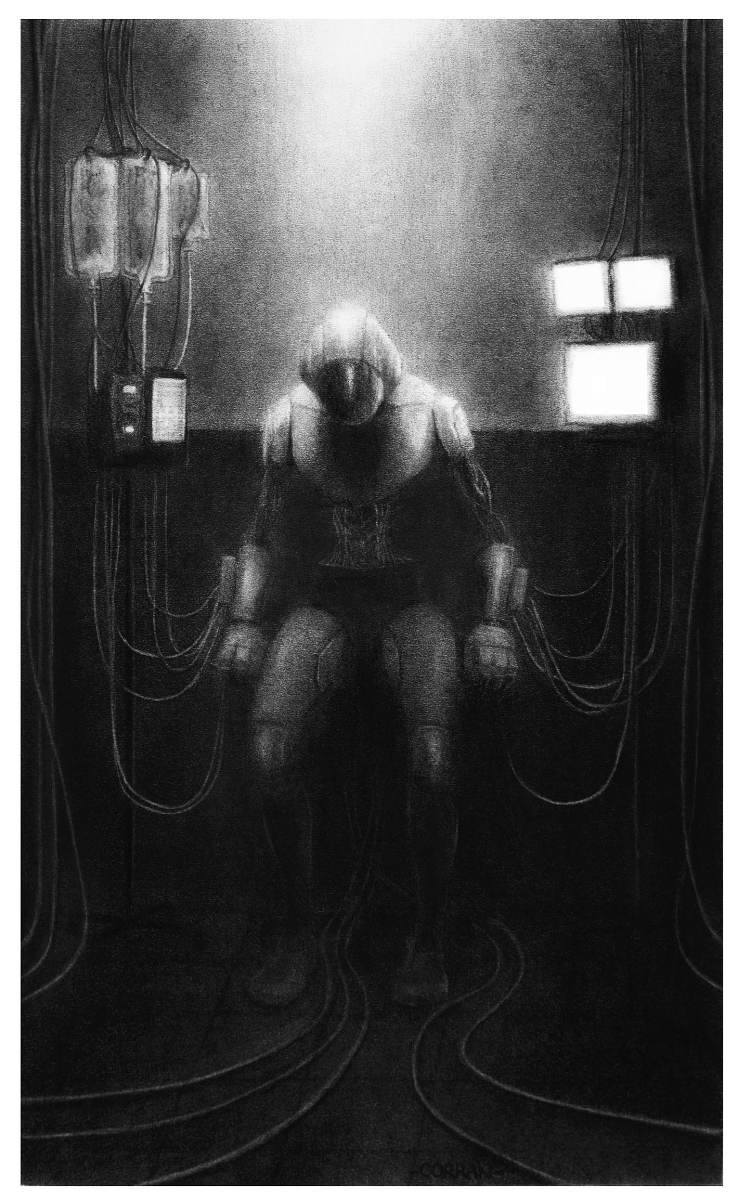

Featured Art: “Frederick” by Denise Loveless

We arrived at Alex’s with our phones tucked discreetly away, each of us carrying something: dip, wine, flowers. I brought my famous seven-layer Jell-O salad. It took all day to make; each of the seven layers had to set before adding another: lime / banana / cherry / grape / strawberry / blueberry / raspberry. But the labor was worth it—translucent rainbow squares that were neither too pretentious nor too generic. Retro. Low in calories.

Alex had laid out games and cocktails. There were candles burning, a record playing—she knew just how to woo us.

We sat around sipping our first drink—something Alex mixed especially for the occasion, a bright green concoction that tasted like candied Christmas trees—catching up on what we’d missed in each other’s lives over the last few months. The lost and gained jobs, the shows and movies we’d binged, the microdosing of mushrooms—or cannabis or K or LSD—the Pilates routines and intermittent fasting. Melissa bought a house—the first of us to own property. A twitch of jealousy moved through us all, though we were enthusiastic in our congratulations. It had a pool.

Read More