By Laura Jok

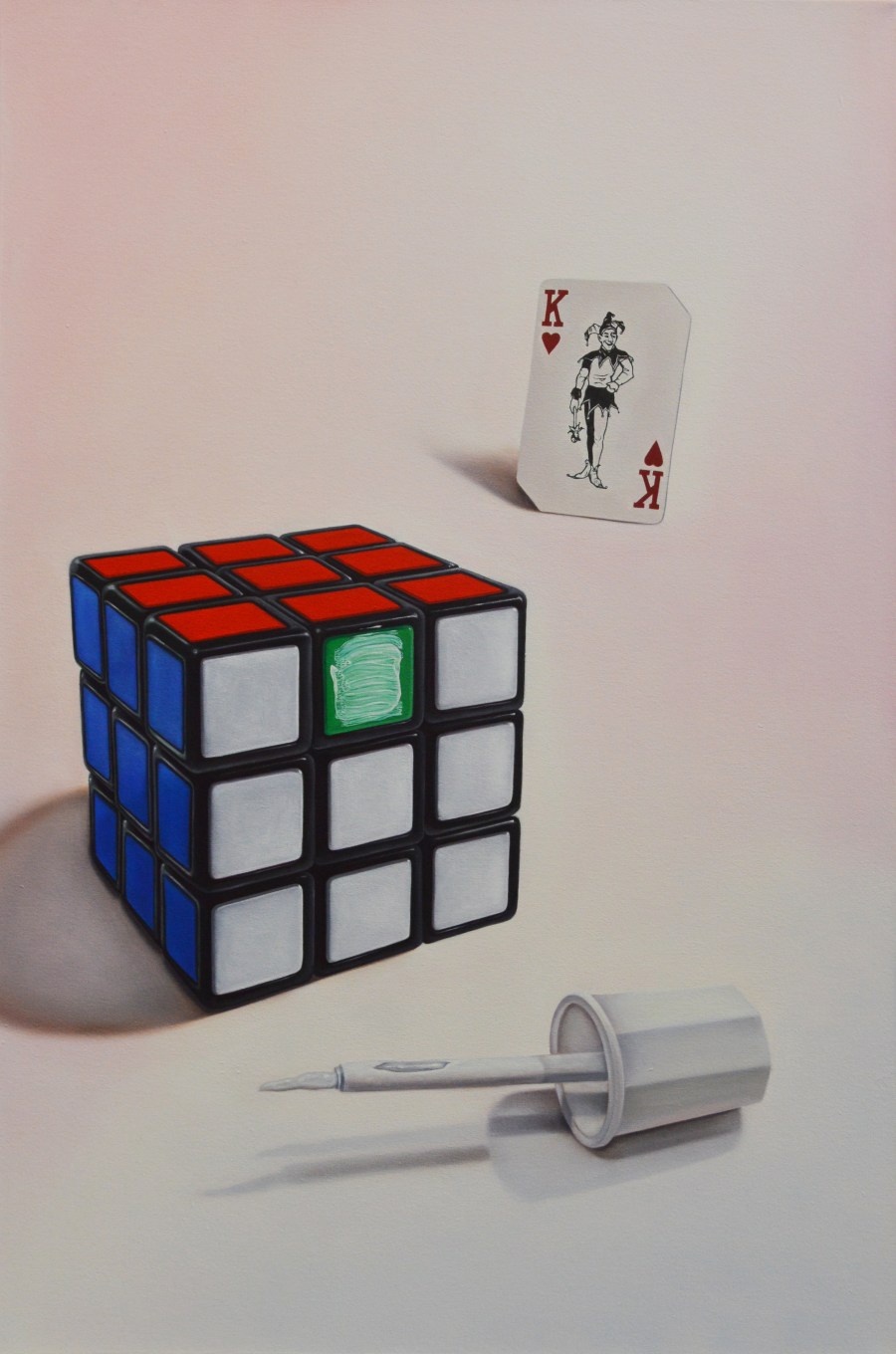

Featured Art: “Untitled” by Elizabeth Boch

You are twenty-six. Donald Trump is running for president. The company that you consider your current employer sees you as more of a friend. The insurance plan that you bought for yourself is hilarious. There is a hole in your back molar about which you are not thinking, which is growing, about which you are not thinking, and you are in love with a stranger who can always be replaced, should he turn out to be a disappointment. You teach other people how to do their jobs like you are some kind of expert.

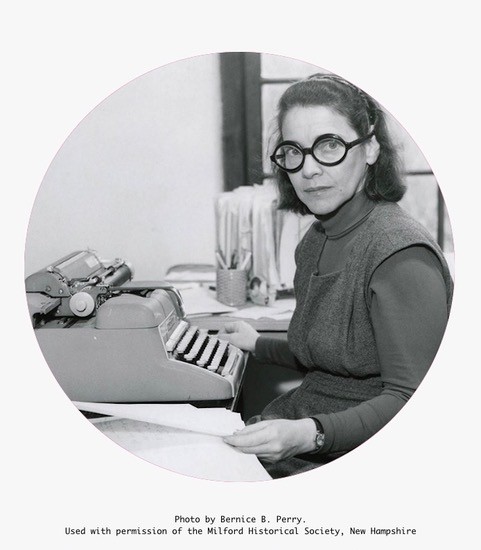

A lowly contractor, you design employee training programs for companies too apathetic to do it themselves. You produce modules: scripted lesson plans, slides. You shoot instructional videos, for which you lure desperate actors. When resources are scarce, you narrate the training, play it back and edit. It does not sound like you: more like someone who knows what to do. You fall into this habit of talking to yourself.

The name of your company is an acronym that no longer stands for anything. In India, where the parent company is based, it is illegal to call anything unaffiliated with the government “national.” About this point in particular, the Indian government is exceptionally litigious. The closet between the green room and your cubicle is filled with worn-out fatigues left over from the last contract with the U.S. Army. When the bigwigs are on a call with Mumbai, you rub the fabric between your fingers. It is not synthetic. It is the real thing.

You used to be a promising costume designer: made it to Off-Broadway, became too disaffected to continue. It isn’t that you weren’t as good as you hoped. It is that no one is as good as you imagined.

The subject matter experts provided by the clients dodge your calls and lie to you. One is in the hospital recovering from a massive coronary and is under no circumstances to be disturbed. Another asks that you arrange your content acquisition calls around his daily psychotherapy sessions. A third prefers to communicate by copying and pasting chunks of text from Wikipedia into the bodies of emails. Every SME wants only one thing: to retire. To get rid of you, they need only pretend that what you are asking for does not exist.

Read More