American Horror

By Jessica Alexander

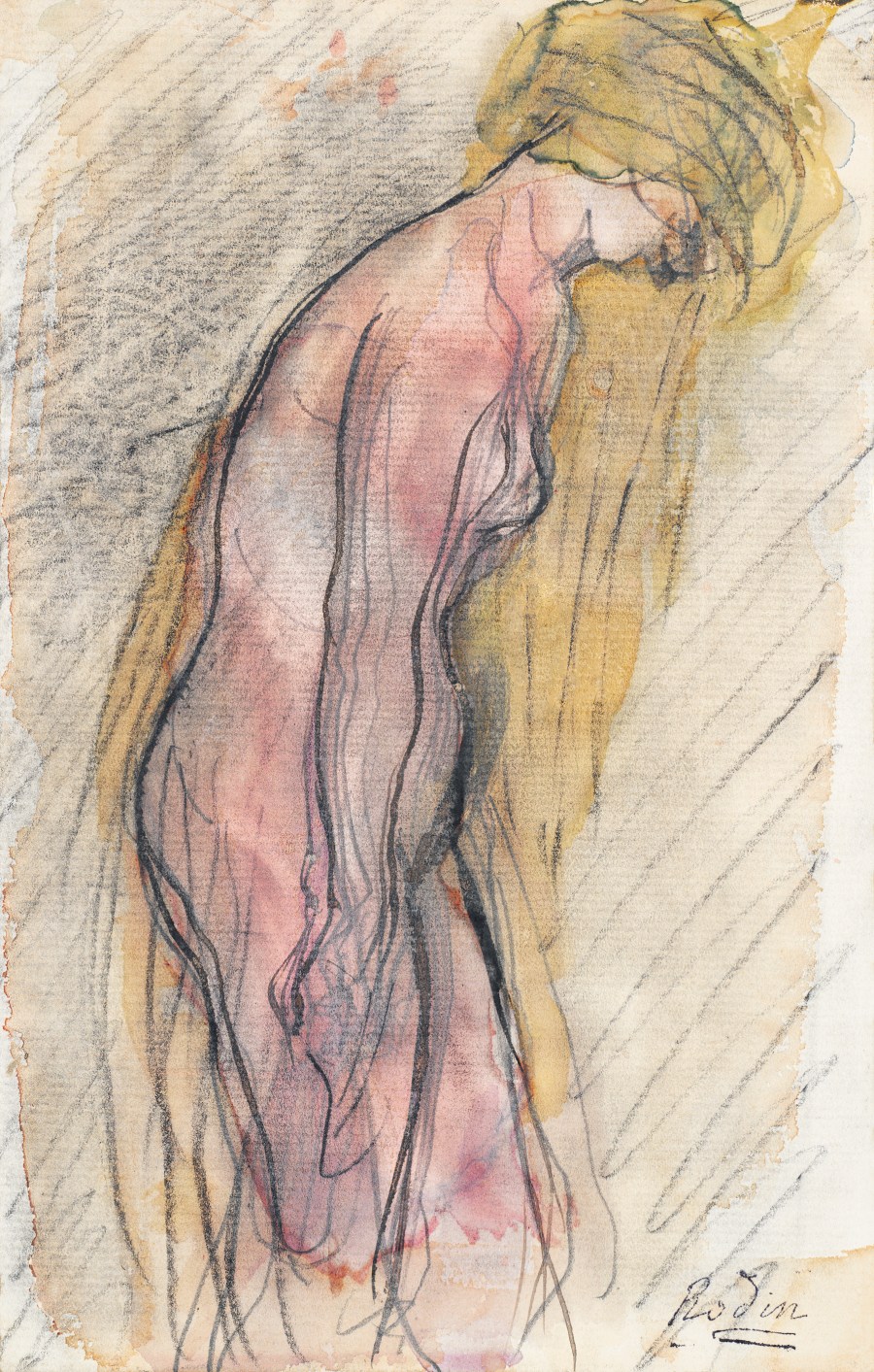

You should have seen me then, under those yellow stadium bulbs, my lips so

full they’d burst in your fingers. I had this top on: a floral print and ruffles, red,

to match my lips, and my tight Levi jeans. And my sun-kissed cheekbones and

the sun-kissed bridge of my nose. And my smile was just like America—like

a cornfield stunned by its own golden beauty—my gorgeous delight! I went

braless, wore no makeup. It rained and the grass was slick. The way it goes is

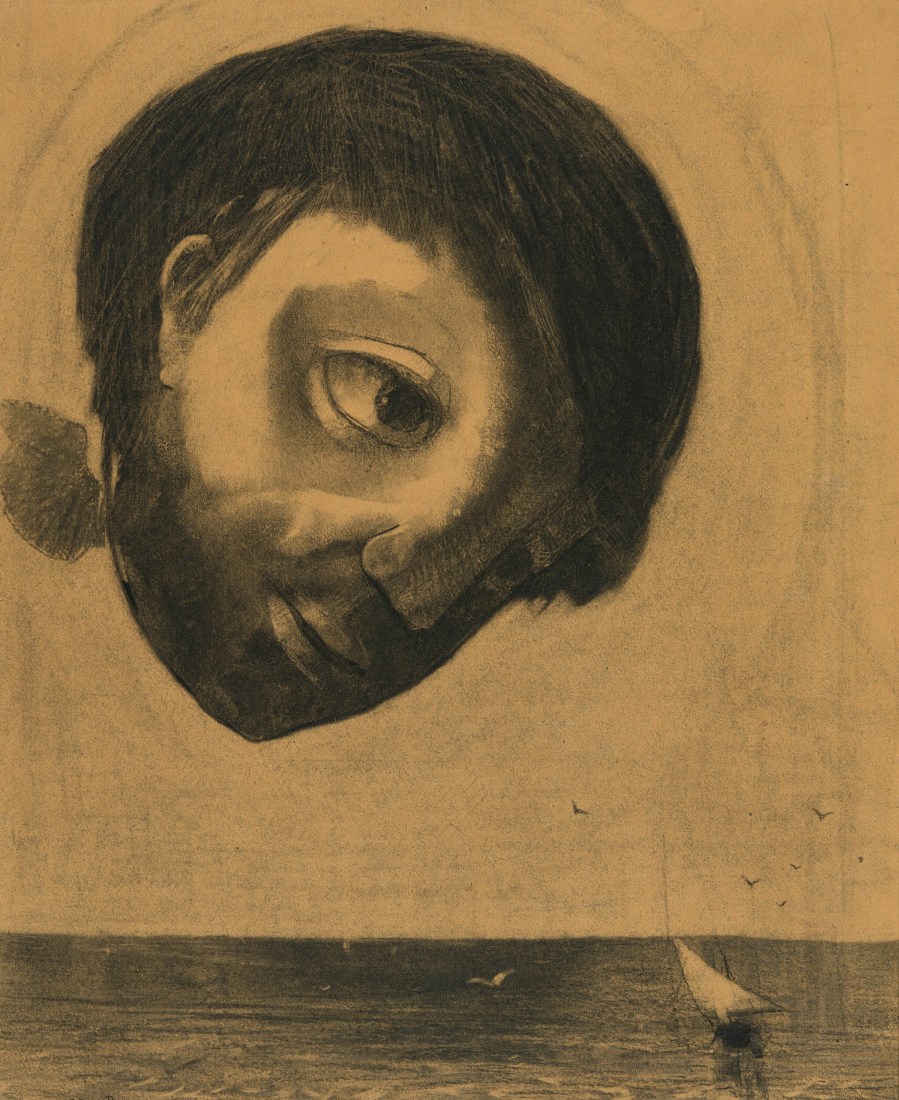

that something happens next. It happens by a lake or in a parked car. You take

one look and know I’ll never survive it. My teeth were like a horse’s. A feeling

they mistake for a girl. A feeling they write songs for. The kind of songs that

played in pickup trucks and there’s me standing in the bed of one, hurling my

top into traffic. Could be a hitchhiker. Some guys carry knives. What is it about

blonde girls and America? Blonde girls and wherever? I was so all–American.

So cute I could have murdered my own goddamn self. What is it about a blonde

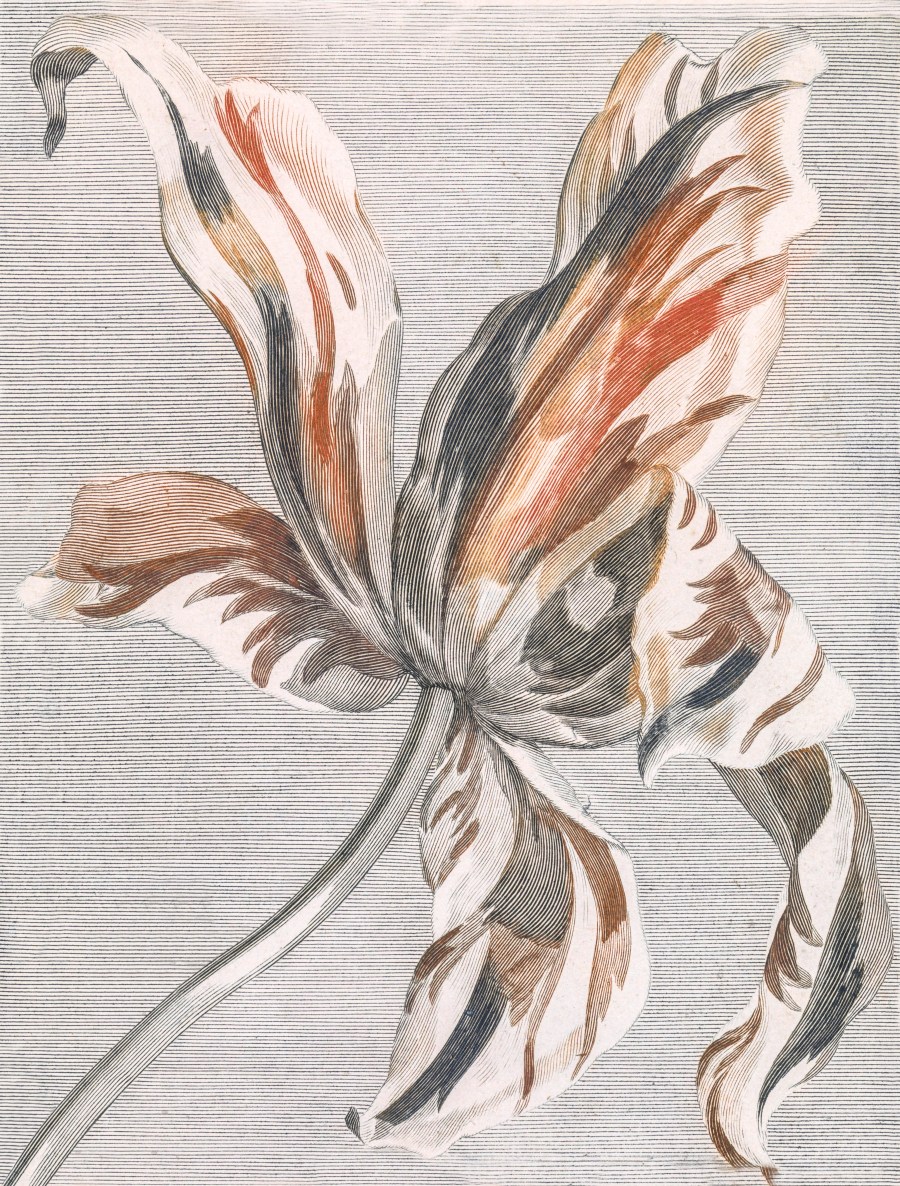

girl that breaks the world’s heart? I miss those days. Not Bobby or Leo or

James. Just miss that particular ache, which was not unlike a bulge in shorts,

that summer rage that could break my chest apart and hurl my beating heart

into the bleachers. Like them I could not keep myself. There is the stadium

again. There is Bobby, cheering. Isn’t that how it happens in America? Topless

in Texas. My little red shorts. In the back of a pickup, again. The window

breaks. In Tennessee? In Indiana? The sound of a power drill, a chainsaw. The

sound of summer. The bleachers, those bright white lights waiting to throw

my shadow to the ground, and there I am, arriving, and it’s always like what

happens to me next has everything to do with every one of us.

Read More