The Dog in the Library

by Catherine Stearns

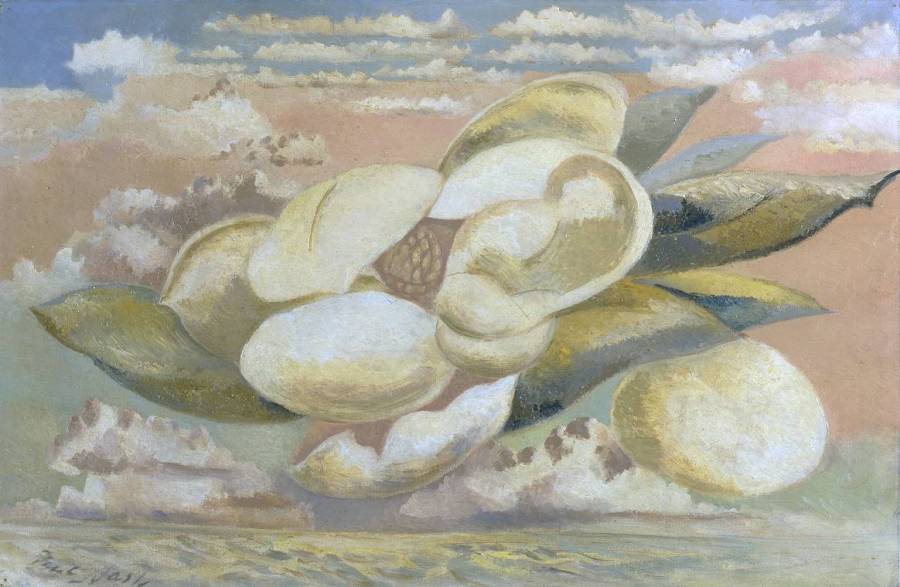

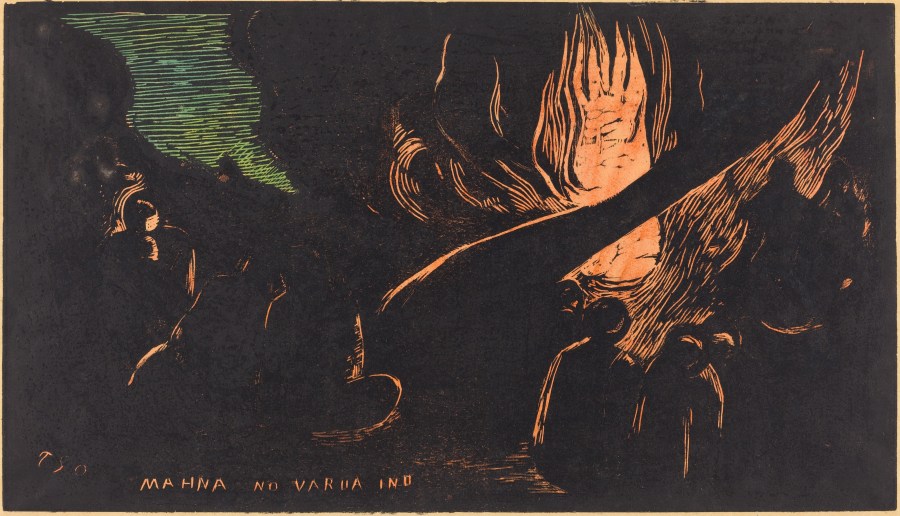

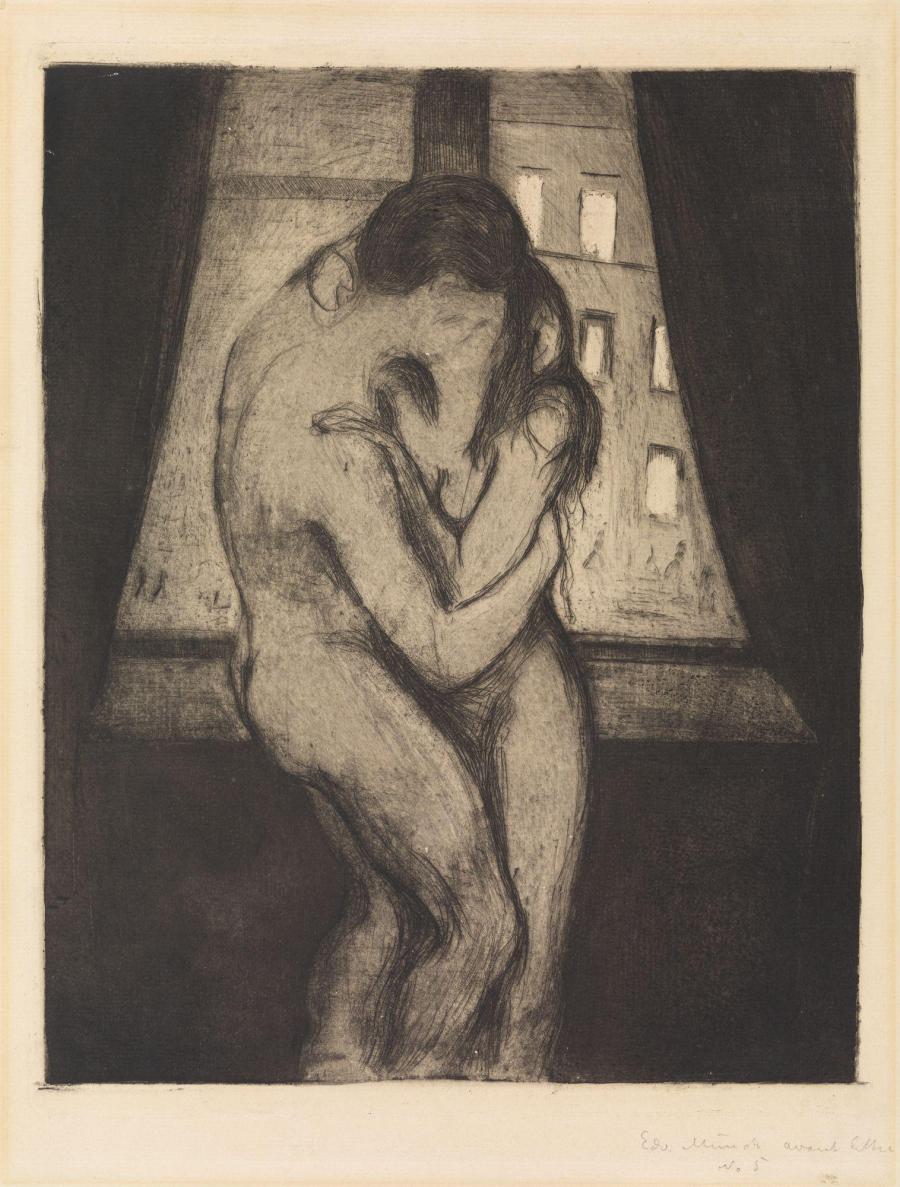

Featured Art: Landscape with Dog by Thomas Doughty

“We may be in the universe as dogs and cats are in our libraries, seeing the books and hearing the conversation, but having no inkling of the meaning of it all.” —William James

On sunny, cerulean days I go all the way

to eleven when I stretch and sniff among the leaves,

whereas you stay inside, hunched over

your moral universe. Old girl, if you

stopped trying to decipher those fossil bird tracks,

you might see the thermal-gliding hawk above

or that zaftig possum gnawing on fallen

persimmons under the window. I’m just saying

your preference betrays a certain fear

of your own nature. Remember

last summer when you left me in the car

to pick up a book they were holding for you,

and a page or two in you recognized

your own penciled and may I say

obsessive marginalia, although you had

no memory of the text itself?

Whatever made you think your mind

could be disenthralled with words?

As a pup, I once took Mark Strand’s

injunction in “Eating Poetry” to heart,

devouring one or two slim volumes,

but soon realized I prefer the raw

material of life, what e e cummings

calls “the slavver of spring”: smells

of fresh earth, the ghostly scent of

rabbits, even the mounds of dirty laundry

piled up on your bed. If you found answers

to your questions, do you truly believe

those answers would transform you?

So many of your species seem

susceptible to revelation. We’re all

browsers, old girl, without an inkling,

waiting by the door for a treat or to be forgiven

until our unleashed immortal part bolts

for that hit of dopamine. Then

all good dogs go to heaven.