“This Time I’m Going to Fool Somebody”: Willie Stark and the Politics of Humiliation

By Dustin Faulstick

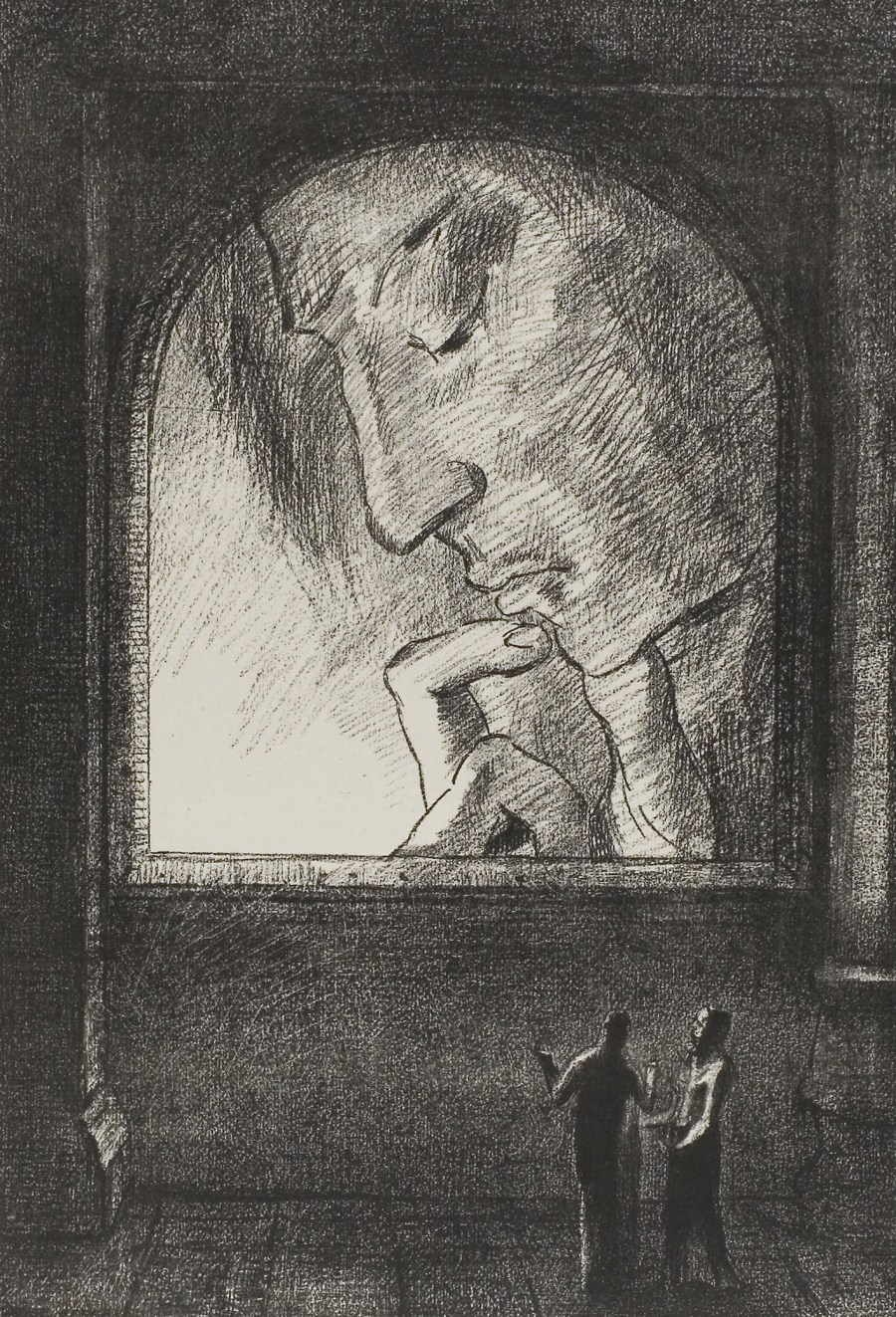

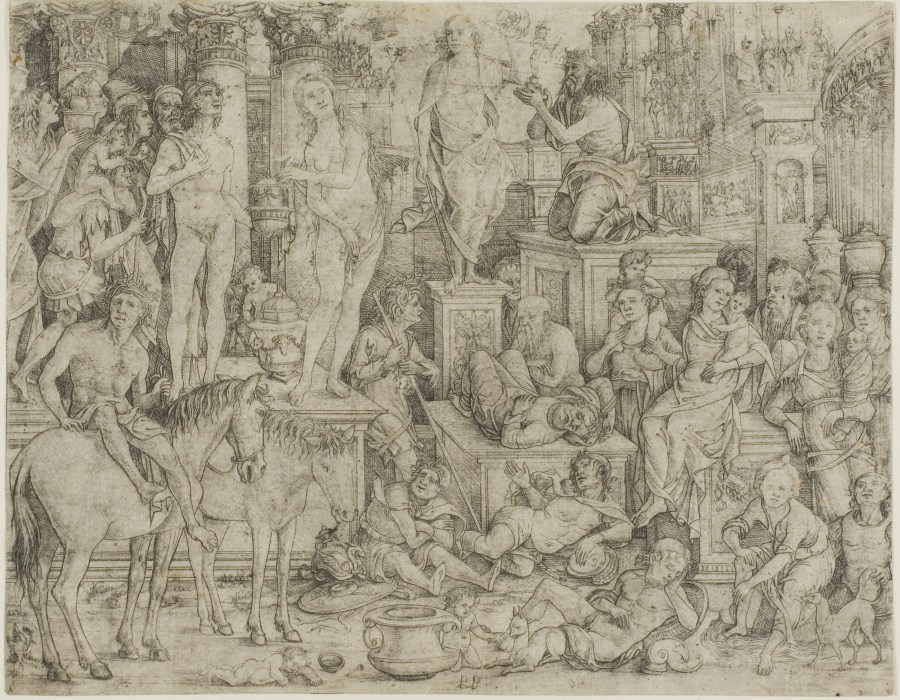

Featured Art: The politician’s corner by Honoré Daumier, 1864

“Folks,” roars Willie Stark on the eve of his impeachment trial, “there’s going to be a leetle mite of trouble back in town. Between me and that Legislature-ful of hyena-headed, feist-faced, belly-dragging sons of slack-gutted she-wolves. If you know what I mean. Well, I been looking at them and their kind so long, I just figured I’d take me a little trip and see what human folks looked like in the face before I clean forgot. Well, you all look human. More or less. And sensible. In spite of what they’re saying back in that Legislature and getting paid five dollars a day of your tax money for saying it. They’re saying you didn’t have bat sense or goose gumption when you cast your sacred ballot to elect me Governor of this state.” From his colloquial diction and insults to his collegial banter with his own supporters, from his invocation of corruptly used tax money to his reference to the sacredness of the ballot, Stark identifies himself as one of the people. Before neurosurgeon Ben Carson or business moguls Carly Fiorina and Donald Trump, farm-boy-turned-lawyer Willie Stark was the ultimate political outsider.

Read More