By Gail Mazur

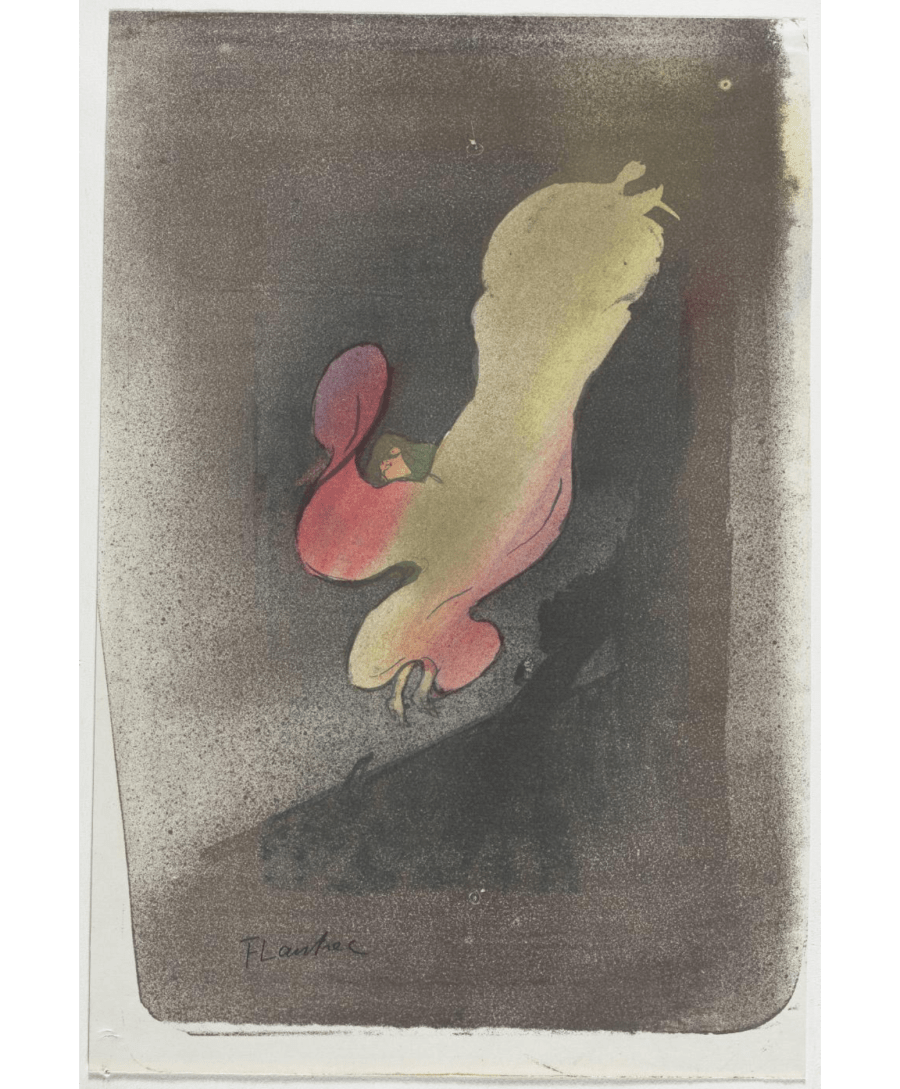

Featured Art: Composition by Otto Freundlich

In your office, you, mastering the art of Photoshop,

scanning a crumpled snapshot, 3 inches square,

of your father, poolside, jaunty in a blue swimsuit,

his straw fedora at a rakish angle,

carrying two splashing cups of bica toward your mother.

Beaming, gallant, tanned, grinning for her camera.

That was in Portugal, in Sintra—

the village Byron called “most beautiful in the world.”

In the old cracked photo,

part of his naked chest had flaked away:

under the glossy surface an ashen patch.

Forty years later at your desk,

filial, in a fantasy of surgery,

you worked your laptop to repair the wound,

dragging pixels of skin tone, of mortal coloration,

from his right side to his left.

A new skill mastered, new language, new tools

that restored but couldn’t save.

I watched you transplant a blush of skin—

a tender ministry, your digital touch

lighter than a kiss—not unlike a kiss—

exactly where his heart four decades

earlier began to falter. As yours, invisibly, did now.

—One of those days we both still thought that somehow

with the proper tools, there was nothing you couldn’t fix.

Read More