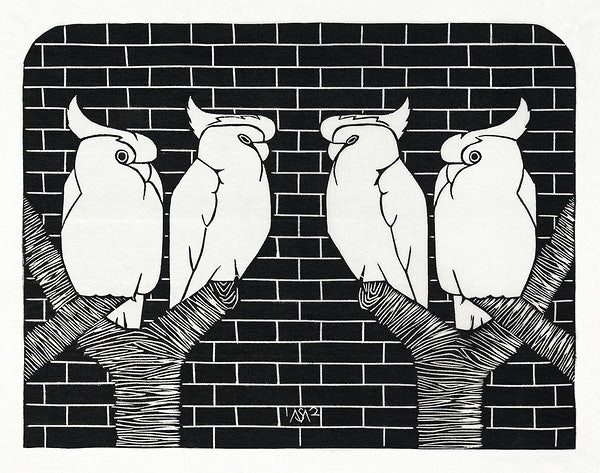

Birds in Cemeteries

by George Kalogeris

It must be the shade that draws them. Or else the grass.

And it seems they always alight away from their flocks,

Alone. It’s so quiet here you can’t help but hear

Their talons clink as they hop from headstone to headstone.

Their sharp, inquisitive beaks cast quizzical glances.

The lawn is mown. The gate is always open.

The names engraved on the stones, and the uplifting words

Below the names, are lapidary as ever.

But almost never even a chirp from the birds,

Let alone a wild shriek, as they perch on a tomb.

And then they fly away, looking as if

They couldn’t remember why it was they came—

But were doing what our souls are supposed to do

On the day we die, if the birds could read the words.

Originally appeared in NOR 11