How to Use This Book

By Christopher Brean Murray

Featured Art: “Summer Figs” by Sherry Pollack Walker

Don’t read it aloud

at the harvest festival.

Never search for a curse word

in its index. Tell the helmsman

the whole thing’s symbolic

from the nickel in the chalice

to the pinecone beside

the Nile. If you travel

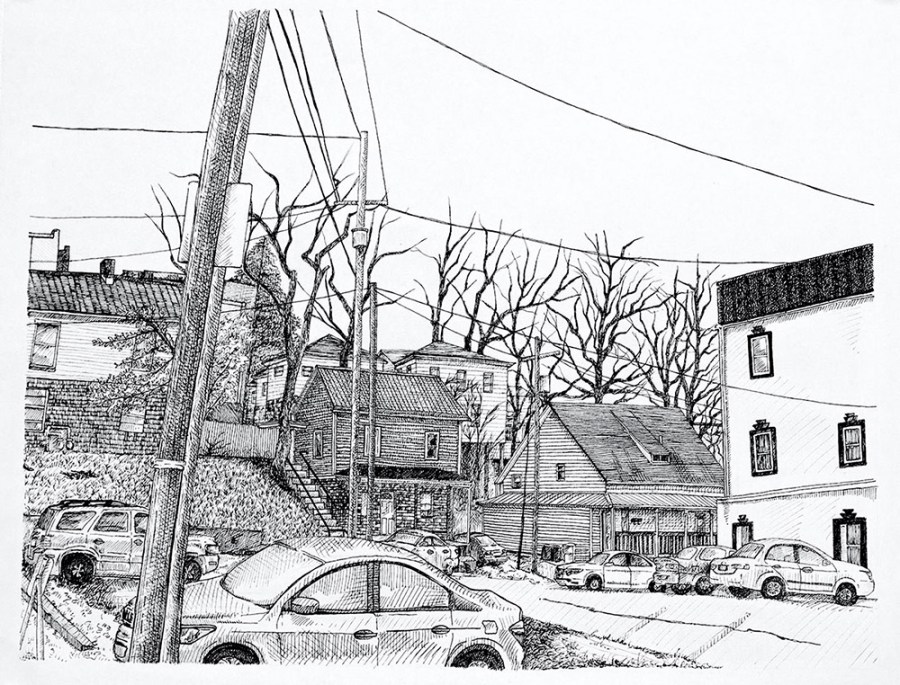

by train, see the image

on page 9. Never place a pear

in the volume’s vicinity.

Don’t walk your dog

on the eve of its release.

Know that its title

is a piece of underworld slang

spliced with a Serbian maxim.

Don’t read the passage set in Khartoum

unless you’ve put your house in order.

If you find a beetle in your drawer

switch one bookmark

for another. Blossoms

on your steps mean

your interpretations

are fruitful. A crash in the distance:

implications have been ignored.

Should you record your reactions

in a journal? If moonlight bathes

a steel bridge in April.

Will the story be made

into a film? Only when figs

write novels. Direct other questions

to the telescope’s designer.

Never shut the tome on a fly.

Read More