By Lawrence Raab

“People who plan their own memorial services,”

my friend was saying, “don’t get the point of death.”

There’d been songs and prayers and ecumenical readings.

Then one of the children played the trumpet

and the brother told too many stories that weren’t

sad or funny. Now we were headed to the reception

to be sincere about how much he’d have appreciated it.

But I liked thinking you could say of someone,

He didn’t get the point of death, and make it sound

like a brave refusal. As we walked up the hill

on that stubbornly beautiful day, I liked that idea

a lot more than hearing about people battling their illnesses

when all they’re really doing is lying there with a chemo drip

in their arms, then stumbling off to throw up. I know, I

know it’s only a figure of speech, a way of granting

courage to those whose bodies can’t manage it,

but what I want is the strapping on of bright armor,

the hefting of great swords, then striding out

into the blinding plain, massed armies on either side.

Sure, the odds are against us. In fact, we’re doomed,

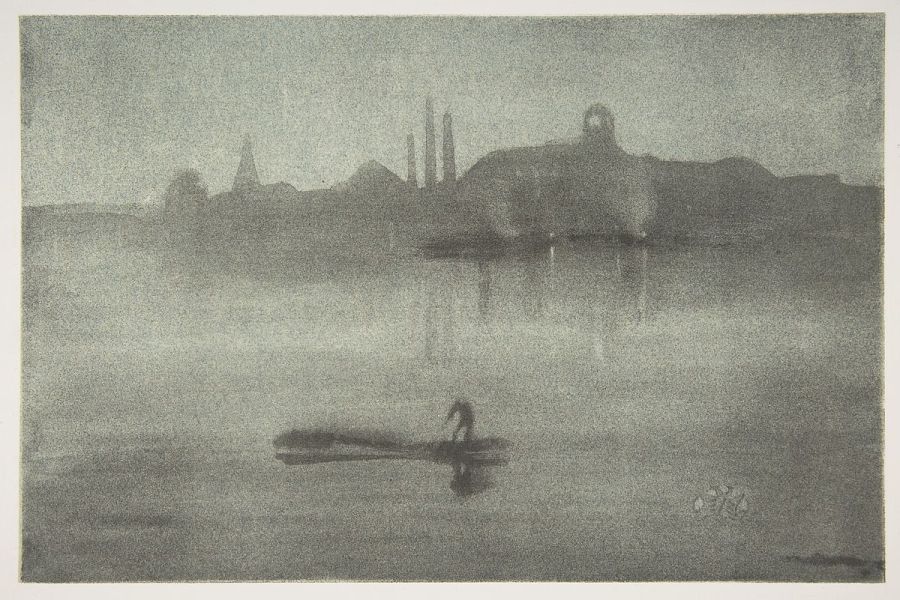

which is why the clarity of standing here

has become important. Not the battle itself, but these

few minutes of stillness—the ocean in the distance

brandishing its light, and the sea-birds inscribing

their invisible maps across the field of the sky,

and the colorful flags of our armies testing the wind.

Lawrence Raab is the author of seven collections of poetry, most recently The History of Forgetting (Penguin, 2009). His collection What We Don’t Know About Each Other won the National Poetry Series and was a finalist for the 1993 National Book Award. He has received a Guggenheim fellowship, a Junior Fellowship from the University of Michigan Society of Fellows, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Council on the Arts. He teaches literature and writing at Williams College, where he is the Morris Professor of Rhetoric.

Originally appeared in NOR 8.