By Mark Neely

I could do without these turkey buzzards

hunched like crash victims

on the water tower’s whitewashed railing

red skulls

poking from the ratty blankets

of their wings. A county over

two taxidermied buzzards hang

from another tower. Their sickly talons

sway in the breeze—

the only thing we’ve found that really works

says the mayor in the local paper.

September. Heat rises in shimmery waves

from the asphalt. The black holes of their eyes

trail me as I sweat through a sluggish run.

They don’t stir, don’t so much as turn their heads.

A few frayed feathers shiver against the sky.

Remember newspapers? They were useful

when we lived with the delusion

we might need each other—under city

bridges the destitute spread

them over heating grates.

I’m guessing water towers will last longer

and vultures, who only eat the dead. I read somewhere

their stomach acids allow them to ingest

meat so rotten it would kill another animal. Like poets

I said, though no one else was there.

I’m always reading things, storing them away

for later. I’m always

chasing down my youth. So far he’s unimpressed.

He prances along in sleek shoes, pays me about as much

mind as groups of jostling teenagers pay me on the street.

I fear these old birds

have a thing or two to say, like grandmothers

warbling behind screen doors. One drops

flaps twice, rides a thermal

traces three wobbly ovals

over the train tracks where the road crumbles

into gravel. I remember the lines

from “At the Fishhouses,” about the seal who visits

evening after evening

a playful opening

in the vast, inhospitable sea.

He shrugs off Bishop’s silly hymns, vanishes,

reemerges elsewhere, making it clear

he’s in his element. Here

streets run down toward the river, houses shrink

their porches falling in

until they finally collapse. My buzzard veers

over the dog groomer’s, the green-shingled nursing home

the Bahá’í temple—no more than a rundown ranch house—

then swoops high above the dentist’s billboard, a fearsome maw

of gleaming teeth. Earlier, Son House came on the radio:

woke up this morning feeling so sick and bad

thinking ‘bout the good times I once had had

I could see him banging his foot

on the juke joint floor, then withering

in a seedy hospital.

Well, we got that over with,

my mother-in-law likes to say

after the parade winds down

or the last guest pulls away.

You like to run? she asked me once, baffled

by any exercise that isn’t useful. I like to have run

I answered, stealing a line from a novelist I heard once, talking

about his labors, the endless straining for the right word

as opposed to the almost right one, which Mark Twain said

was the difference between the lightning bug

and the lighting. A few cars flash in the distance

as I cross over onto the greenway, a gray path

winding along the river like Ariadne’s thread—

she helped a man who didn’t love her

find his way. Sound familiar?

Sometimes I catch myself

wishing the day would end. Or try to leap

whole years, even as they spool away.

We used to call this human nature.

Bishop thought of knowledge

as a kind of suffering

a dark expanse

we can only skirt the edges of…

Inside the tower’s globe, an ocean

waits for another emergency—

metallic, unthinkably heavy

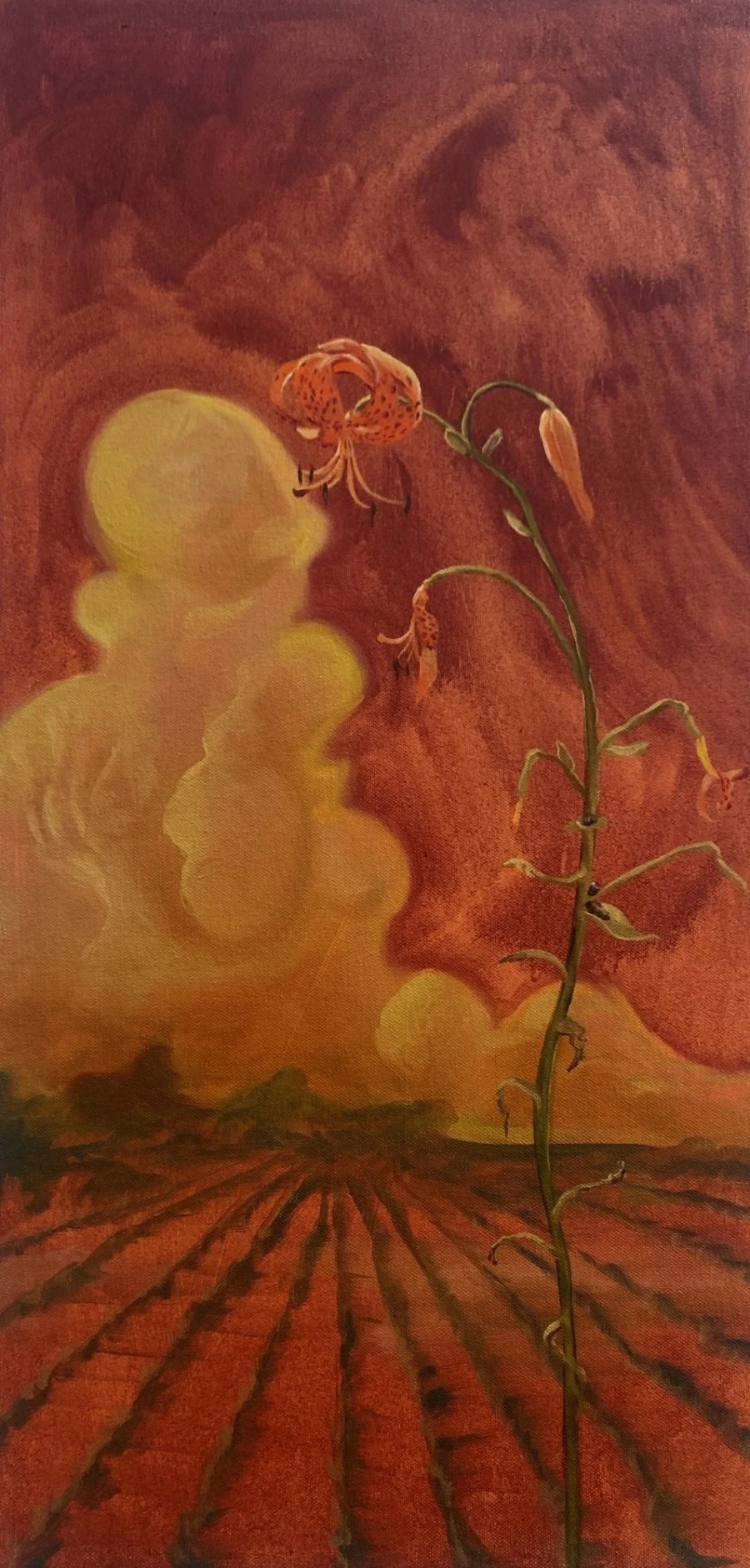

drawn impossibly into the sky.

One morning I watched three buzzards

huddled by the road, tearing at the pink entrails of a possum

knocked into the ditch as it scuttled through the night.

Curious, bathed in blood

incapable of mercy, they bowed like monks

over the body.

As they tore at the animal, one fixed me

in her stare.

Look here, she seemed to say.

I wanted to conflate carrion

and carry, to imagine an airy chariot

ascending from the corpse.

A delivery truck rattled around the corner

and startled the birds into flight, where they joined the host

swirling above.

Carnal, of course

is the word I was looking for—

Read More