Dinosaurs in the Basement

By James Davis May

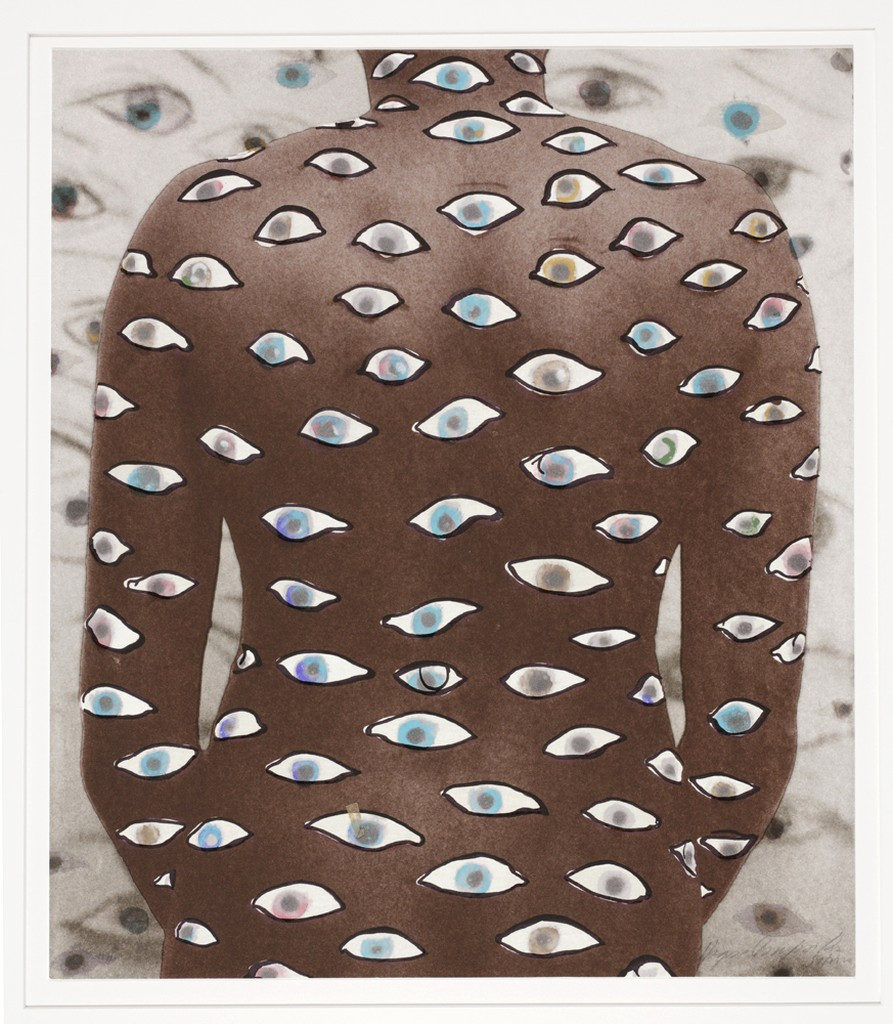

Featured Art: “Jesus Diptych” by Christopher Shoust

Jumbled in a box buried under a sediment

of obsolescence—

busted luggage, boxes of VHS tapes,

tubs stuffed with old baby clothes—they’ve suffered

a second extinction, their snarls and scowls

all petrified

in a kind of afterlife: not damnation,

exactly, more of a removal, an excommunication

from the child who made them lunge and jump,

growl and roar, loving them

like a god obsessed

with entertainment. Then one day, a lid eclipsed the light

like an indifferent ash cloud and did not lift again

until just now,

when looking for something else,

I found their box instead and slid it from the stack.

Even coughing from the dust, I’m surprised

by how happy I am

to see them, and place one,

the triceratops, in my palm, holding it up

to the bare lightbulb to study the gray pebbled skin,

the beak opened

in what looks like shock.

She once believed those horns could fight off any danger,

but all they do is scratch me from inside my pocket

as I climb the stairs

back into time, answering

that voice that at least for now still calls for me.

Read More