[Philosophy Is a Way to Find Out . . .]

By William Archila

Philosopy is a way to find out god left long time ago. Correction.

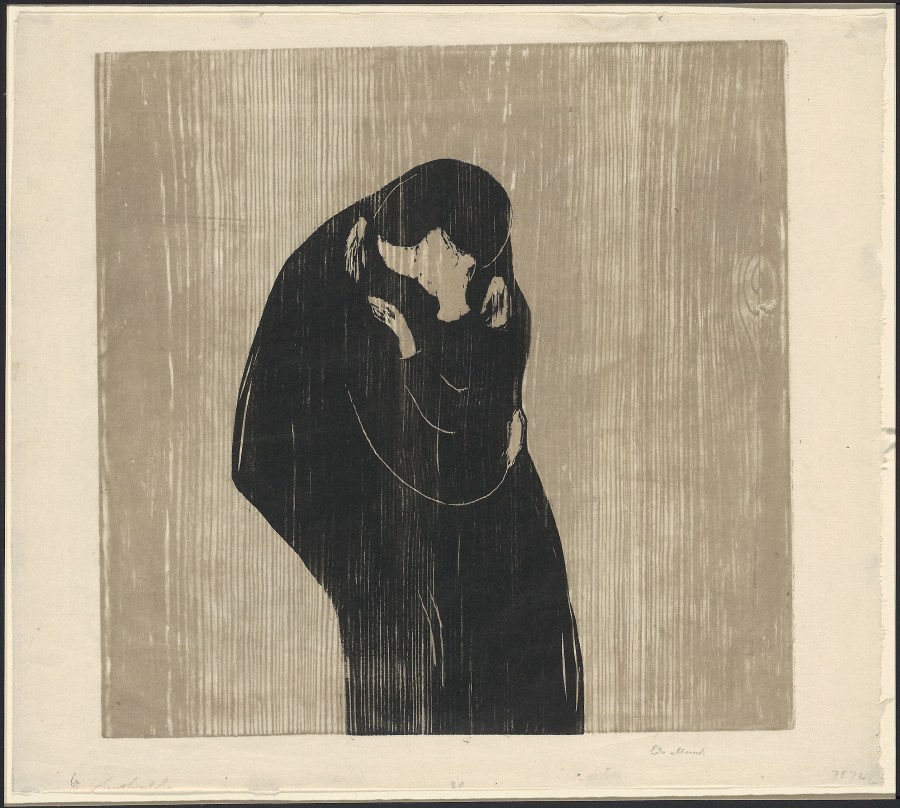

Philosophy is a way to catch on we are the only gods left. Death

is an endless war against philosophy. Correction. Death is a reminder

we’re already dead. Is history what we forget but are reminded

again & again? Is religion a different method to talk to our future

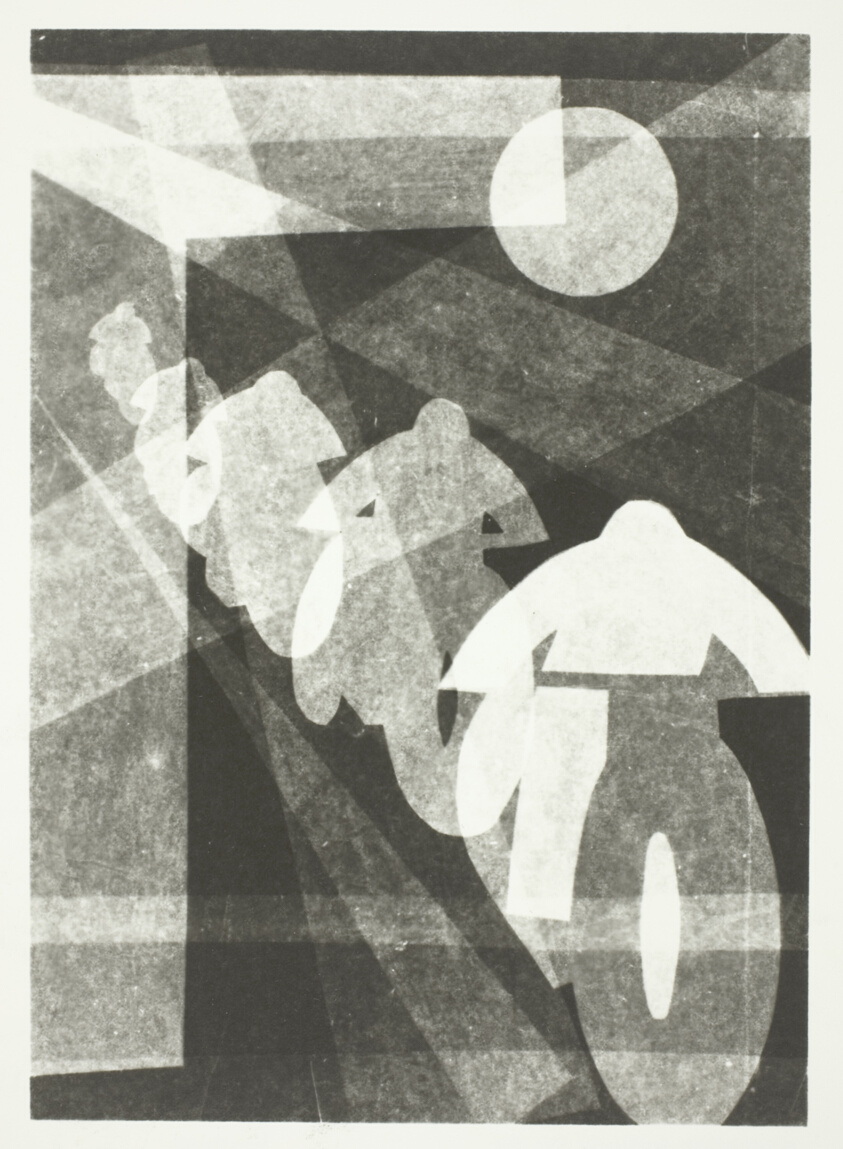

selves. Darkness is a joy to find out anything is better in the dark.

Colonization is to put the land in a casket then sell it to another cop.

Let me try again. My professor says colonization is what colonizers

did to his mama. A migrant caravan is a ship of settlers seeking land

& jobs. Repeat. A migrant caravan is a ship with white sails seeking

a bed & a good shower. Americans are anyone born in the continent

named after Amerigo Vespucci. Yes, Nicaraguans are Americans, too.

Disappearance is to live inside a skull that is too small for the mind.

There are people very good at that. I don’t know what else to tell you.

Read More