Tag: 2019 Winter

Coyotes

By Terri Leker

Winner of the 2019 New Ohio Review Fiction Contest, selected by Claire Vaye Watkins

The coyotes moved into the woods behind my house just after I learned I was pregnant. On a quiet June morning, while my husband slept, I pulled on my running shoes and grabbed a leash from a hook at the back door. Jute danced around my feet on her pipe-cleaner legs, whining with impatience. It would have taken more than this to wake Matt, but I hushed her complaints with a raised finger and we slipped outside. A light breeze blew the native grasses into brown and golden waves as we wandered, camouflaging Jute’s compact frame. She sniffed the dirt, ears telescoping as though she were asking a question. When we reached a shady thicket of red madrones and live oaks, I unclipped the leash and wound it around my wrist.

It was over with Richard, had been since I’d found out about the baby. Anyway, I had come to believe that adultery sounded more illicit than it actually was. Between managing my schedule with Matt and making time to rendezvous with Richard, an affair often seemed more about time management than sexual gratification. I was meticulous with the calendar, but I would have known that the baby was Matt’s regardless, because Richard’s sperm could not locomote. He had told me so early on, while showing me the master bedroom of his faithfully restored North Oakland Victorian. His unexpected disclosure had interrupted my admiration of the exposed brick walls, so unusual for the earthquake-conscious Bay Area. Matt was having dinner just then with friends, thinking I was helping my mother set up her new television (she would be dead within a few months, but we all pretended to be optimists then), so he was eating eggplant parmesan at the Saturn Café as I lay with Richard on his king-sized bed, hearing words like motility and capacitation. Richard’s sober tone had suggested that I might comfort him in his sterility, which I did, if the definition of comfort was a passionate encounter that lasted as long as one might spend unboxing a 48-inch HDTV and connecting it to both Netflix and Hulu. But Matt and I had tried to have a baby for three years, so I took the pregnancy as a sign to recommit myself to my husband, who, predictably, jumped up and down on our unmade bed when I shared the news, attempting, in his white-socked excitement, to pull me up with him, not realizing that doing so might judder the bundle of cells loose, delivering me back to Richard and a childless but aesthetically pleasing life.

Read MoreRevising Bosch’s Hell Panel for the 21st Century

By Kelly Michels

“Hundreds of couples toting AR-15 rifles packed a Unification church in Pennsylvania on Wednesday to have their marriages blessed and their weapons celebrated as ‘rods of iron’ that could have saved lives in a recent Florida school shooting.” Reuters, Feb. 28th 2018

They come wearing crowns of gold bullets in their hair, bodies drenched

in white satin, white lace, tulle, lining the pews on a weekday morning,

AR-15s in their hands, calling on god to save them. There is no

such thing as salvation, only the chosen and too few are chosen.

Children are told to stay inside, schools locked shut, swings hushed,

even the wind says, quiet, as the guns are blessed, dark O of mouths

waiting to exhale a ribbon of smoke. The children are told to crouch

in the closet, to stay still as butterflies on butcher knives

while the men take their brides and iron rods, saluting the book

of revelation, its scribbled last words, the coming of a new kingdom.

Don’t speak. Don’t breathe. Pretend you are an astronaut gathering wisteria

twigs in a crater of the moon. Pretend the twigs are the arm of a broken mandolin.

Someday, it will speak. Someday it will sing. Dear God, bless the self in the age

of the self, bless this bracelet of rifle shells, bless our god-given individual

right. I know you want to sing. You want to sing like blackbirds escaping

from the mouth of a grasshopper. But remember, we are only here

for a little while, so for now, keep quiet, pretend we are somewhere else.

Pretend we’re practicing our handwriting, the lollipop of a lowercase i,

the uppercase A, a triangle in an orchestra, the different sounds it makes

if you strike it the right way. Practice the slow arch of a R. Now—

form the words. Scribble run, scribble come, scribble mom, scribble when

will this be over? But for god’s sake, be quiet. Don’t cry. Just write. Scribble

on the walls, on your arms, scribble as if it’s the last thing you will ever say.

Pretend it sounds like music. And if the devil comes through that door, remember

to go limp, lie on the floor like a tumble of legos. Don’t move. Don’t speak.

Don’t breathe. Pretend you’re already dead. Remember, this is how you live.

Read More

American Bachelor Party

By Conor Bracken

Featured Art: Star and Flag Design Quilt by Fred Hassebrock

Here I am inside a firing range.

Loading and holding and aiming a pistol

the way America has taught me.

Hitting the paper target in

the neck the mullet the arm the arm.

The old-growth pines inside me

do not burst into orange choruses of flame.

I am disappointed I’m not making

a tidy cluster center mass.

Around me fathers and offspring

as plain as stop signs give

each other tips while they reload.

A man one stall over cycles between a revolver and a rifle

while another draws a Glock

from a hidden waistband holster

over and over again, calibrating

his shift from civilian to combat stance

with the dead-eyed focus of a Christmas shopper.

These could be my people.

If I never talked

about the stolid forest inside me

planted by those I do and do not know

who died because America allows you

however many guns and rounds you can afford—

if I never talked about my manliness

that runs cockeyed through the forest

trying to evolve into an ax or flame or bulldozer

so it can be the tallest, most elaborate apparatus

taming local wind into breath,

they might give me a nickname.

I could practice training my fear with them

like ivy across a soot-blacked brick façade

and they might call me The Ruminator.

Virginia Slim.

Spider, even.

We’d grow so close that they would call me late at night

asking for an alibi again

and if I asked groggily ‘who’s this’

they’d say ‘you know who’

and I would.

Their name blooming from my mouth

like a bubble or a muzzle flash.

A flower

fooled out of the ground

by the gaps in winter’s final gasps.

Read More

Red Flags

By Whitney Collins

Featured Art: The Kiss by Max Ernst

The first thing Ilona saw when she got to the beach was the man, bleeding from his leg with a crowd of people around him. She was far up and away in Bill’s condominium, looking down at him from the master bedroom window with her two suitcases in her hands. The man held out his bleeding leg for everyone to admire. Half of the crowd looked down at the leg, half looked out at the ocean. After a minute, the man spread his arms out wide as if to show everyone how much he loved them. Thissssss much.

“It faces the beach, see? Just like I promised.” Bill came up behind Ilona and palmed her breasts. “What a view, huh?” But Bill wasn’t looking at the view. He had his short face in Ilona’s long neck and was missing out on the man and the leg and the crowd, which was just fine by Ilona. When Bill went out into the condominium’s kitchen, to show her sons some sort of fishing contraption, Ilona went right up to the window, still holding her luggage, and kissed the glass. She had been darkly depressed about herself and her life the whole trip down, and then the man with the bleeding leg appeared and something lightened in her. There was still some good in the world.

*

The first night, Ilona pretended to sleep in the guest room, to set a good example, but when she could hear her sons breathing deeply from the adjacent room and knew they were asleep, she went into the master bedroom and got into bed with Bill. She had accepted Bill’s proposal mostly—no, entirely—because she was penniless. Her husband had drunk himself to death because of the debt, and all she was was a speech therapist. How was she to pay for her youngest’s lung medication, much less electricity and soup? It only made sense to sleep with someone like Bill, even if the new ring lay on her finger like a lead bullet.

Read MoreThe Dock Hand

By Kathryn Merwin

this is a poem about losing things.

not a poem

for the boys who barreled their broken

bodies into the lightningwalls

of my body. for the knife

of let me

in, baby, the trigger-finger

of let’s

go back to my place, just one drink.

you, draining the blue

from my veins, dyeing

empty sheets of skin,

blue again, purple,

blue. the color

of healing of bloodpool

beneath skin. for the crushed

powder in my jack & coke of

no one will ever believe you.

you’ll spend the summer in alaska

and we’ll both pretend

like we’re not losing

something.

you have no idea

what i’m gonna do to you.

yes, I do.

Read More

A Cure for Grief

By Emily Franklin

Featured Art: Still Life With Apples and Pears by Paul Cézanne

There isn’t one. But here is a pot of jam,

apricots plumped with booze, lemon rind, sugar—

the stuff of August evenings,

of dirt roads trimmed both sides

with heavy woods that narrow and finally

funnel to the ocean. To the house

on Buzzard’s Bay—deck built, rebuilt,

expanded and rotted, built again, everyone

toe to thigh on chairs, neither comfortable

nor attractive, scattered each afternoon

as we scrubbed clams collected in low tide

or painted rocks or read the paper

or stared out as though we knew it was always

on the verge of ending. Those nights,

jackknifed open with wind and visitors,

dinner not yet cooked, someone asking

someone else what was ready to be picked;

green beans knocking like wind chimes,

nubby new potatoes, the summer’s experiment

with asparagus that we wouldn’t trim—

each stalk pushing and protruding until it appeared

a new creature had clawed its way up from the earth.

Now I offer this: apricot jam from last summer

that we did not know was last. Your instructions:

unscrew the Mason jar, cribbed from the Cape pantry.

Each morning you will awake alone. This is when

you dip your teaspoon or knife into the jam

or even your piece of actual bread. No one is judging—

insert crust directly into jar. Taste the apricots.

For this moment have summer—

and him—back. The jar is large. So is grief.

This is what you’ll sample each day,

fruit slipping against lemon, and sugar, and time.

When the jar is empty, days will have been

gotten through, too.

The porch is rotting now, joists breaking loose,

everything undone as though he—and the rest of us—

are already gone, but let us be suspended

right there at 5pm, drinks in hand,

sun still up, children barely grown.

Eat the jam. This is all we have to offer.

Read More

Thresher Derby

By Patrick Bernhard

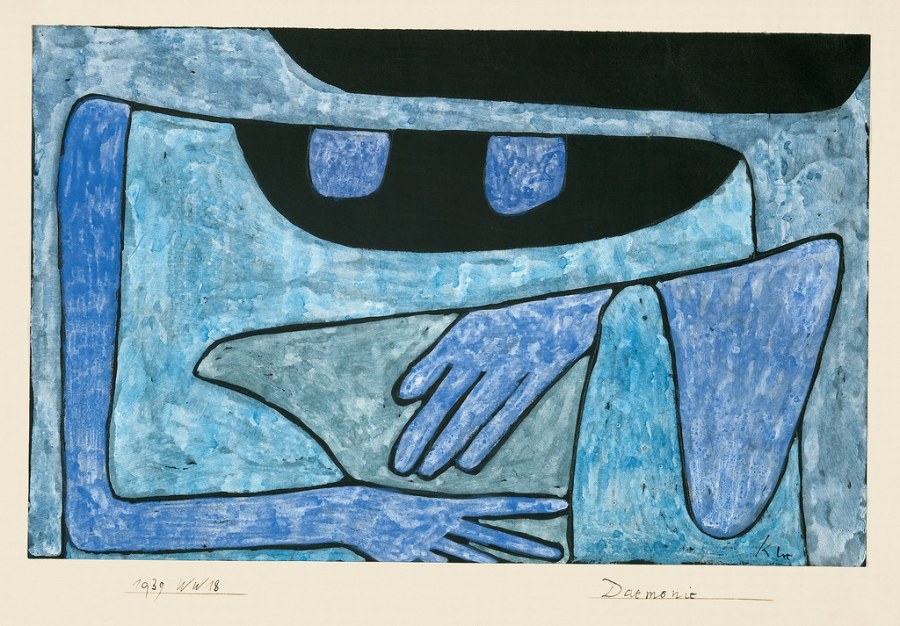

Featured Art: Daemonie 39 by Paul Klee

The undertow had carried Daisy far enough out to sea that her bullseye swim cap probably looked like a floating pastry to the judges, even with their binoculars. She hoped that rest of her looked similarly delectable to the Medium-Class blues that the scouting report had placed a reasonable 19% of hunting in the Frontier Belt; nobody had caught anything elsewhere, outside of a zebra shark that wandered into the Sandbar Belt that the chatterbox from Bethany Beach managed to cosh, catch, and drag. Not that she was worried by that bag; Chatterbox’s zebra had the telltale torpor of a bad fungal infection, so it barely put up a fight, and she’d repeatedly coshed more dorsal than skull and in shallower water, too, losing major accuracy marks that she couldn’t afford to have subtracted.

Daisy’s choice of enticement pattern – tread for ten seconds, followed by a burst of strategic thrashing – was fairly exhausting, with the current more active than the lifeguards’ flags were indicating, but the rumor was that deep-water endurance played up heavily with the judges at this particular beach, mostly due to sentimental reasons. It was apparently at this depth that the woman that this derby was named after, Betsey Gulliver, managed to drag in a four-foot thresher even after a whip from the tail of the shark in question had lacerated her left eye and given her ear a flat top. Thus, the parameters for this derby’s Spontaneous Technical Victory – cosh, catch, and drag a Medium-Class thresher – were established. The banner reading “Betsey Gulliver’s Thresher Derby” was stretched above the stands like a giant volleyball net, painted in garish lettering whose crooked slant was evident even from where Daisy was, as if the banner had been made in a group effort by the local middle school.

Read MoreLunch Duty

By Barry Peters

What I know of her

cackling in the back row,

sassing the boy next to her,

absent, tardy, bathroom pass,

not doing any goddam work

and this is the easiest

history class in the history

of American education:

what I know of her

is that for one moment

each day, after escaping

the apartment,

the bus fights,

first-period algebra,

second-period biology,

third-period gym

she hunkers down alone

in a corner of the cafeteria

communing with some

XXtra Flamin’ Hot Cheetos,

oblivious to the orange

residue on her teeth,

smiling as she offers me

the open cellophane bag.

Read More

Lucy’s

By T.J. Sandella

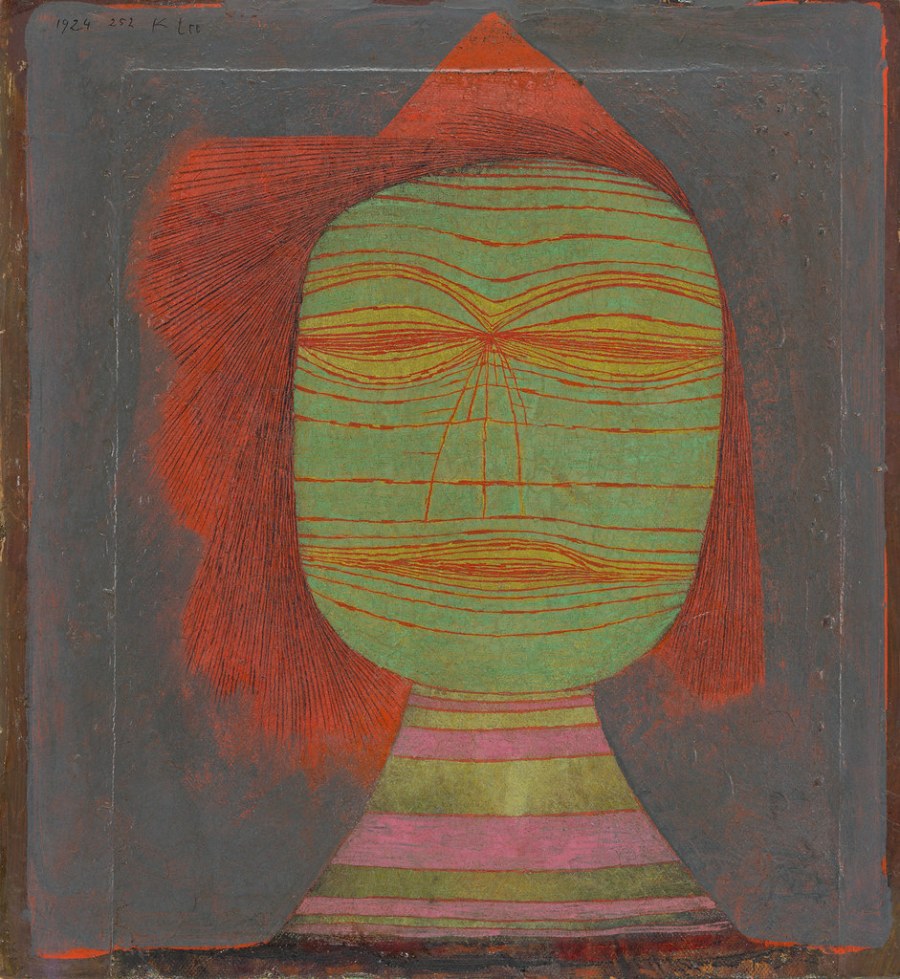

Featured Art: Actor’s Mask by Paul Klee

I confused guacamole

with guano

until I was seventeen

when my girlfriend’s mom

patiently explained the difference

plopping a dollop onto my plate

next to the Spanish rice

catapulting me

on the long flight

from meat and potatoes

to masala and paneer

for the first time

as a freshman in college

tartare and foie gras

as a grad student

and so it goes

the older I get

the farther I travel

with my tongue

curries and compotes

caraway and cardamom

ginger and jasmine

and planes and trains

to aromatic rooms

in cities I can taste

better than I can pronounce

which have all led me here

Read More

Deluge

By Rachel Eve Moulton

Sara doesn’t sleep anymore. Not for more than an hour at a time. Her body feels sore, her joints loose, as if a leg could slip free if she isn’t careful. It’s May, her first spring in the house, and the rain has been falling steadily since early April. The Mad River jumped its banks some weeks before, and, in a gesture of solidarity, Sara’s body has ballooned at the ankles, the thighs. She’s 38 weeks pregnant with twin girls, and even her fingers have grown thick, her wedding ring now worn on a chain around her neck.

Sara is beginning to think she’s made a mistake.

Her friends told her that from the start. Who gives up their whole life for a man they barely know? They took bets on how long she’d stay, calling up to see if he’d turned out to be a serial killer. But, when she announced the pregnancy, the jokes stopped. Phone calls stopped too, as if no one knew what to say to her anymore. The only bright spots were the times she allowed herself to dream about her past selves, a hundred different versions—waiting tables in the little black apron at 16, skin smelling of bacon grease; the summer she was so poor that she only ate peanut butter; reading in the gaudy canopy bed she’d had as a child; and the graffitied bathroom of the club where they’d danced to 80s music in college. Although it scares her, if the babies weren’t an actual part of her physical self, she would flee. Leave this sudden husband in search of Louisville or any one of her past selves, because this one. This one. This one would not do.

Read MoreHeartbeat Hypothesis

By Robert Wood Lynn

As it turns out there is this silly trick to knowing how long you,

no anybody, no any creature will live:

divide the average lifespan of an animal by its metabolic rate

and you will get a number that is about one billion. That’s what we get,

about one billion heartbeats on this planet

one billion, a magic enough number and even though physics has struggled,

struggles and in all likelihood will continue to struggle forever to find

its unifying equation, here is biology’s, the kind

of surprise you trip over because it has just been sitting there all along,

like a golden retriever on shag carpeting, one already most of the way

through her billion and where she is joined by

the field mouse and the blue whale each getting one billion beats on Earth

unless someone or something intervenes and quiet now you can hear it

tick ticking away, your billion ticking like the kind

of clock they mostly don’t make anymore and once I believed that

in every clock there were tiny creatures moving the parts and now

I cannot help but know inside of these creatures

there are more parts marching even faster to the same number

onebillion onebillion onebillion and it can drive you mad even

billionaires go mad cartoonishly mad with the one

thing they cannot buy more heartbeats and they sit in a tube someplace

air-conditioned in Arizona their rhythm frozen while animated mice

power the clocks and calculators that keep this math

like a metronome: terrible, free.

Read More

Somewhere Outside of Loveland

By Amy Bee

Featured Art: “Design for 4-seat Phaeton,” by Brewster & Co.

My mom kicked me out this morning. If you’re still here by the time Doug gets home, I’m having you committed, she said, so I put on some jeans and ran to my old elementary school across the street. I headed toward the two tubes next to the monkey bars. I’d spent a lot of recesses in those coveted tubes. Now that I was in 8th grade, the whole playground appeared fake somehow, like a toy model version of itself.

I ducked into one tube and lay so my body conformed to the cool, smooth curvature of cement. Wrapping my arms around my knees, I pressed toward my chin, and wished myself as small as possible; maybe I could also be a toy model version of myself. Phantom spasms of her anger coursed through me like a second heartbeat. The way she’d sat on my back and pulled me up by my hair to hit my face. How no one loved me, she’d yelled, no one except her. How she was the only one who wanted me in the first place.

I gazed at the graffiti inked in marker crisscrossing the ceiling above me. It read like a map of the universe conceived by grade school astrologers. Terry eats poop! Stay 2 cool 4 school xoxo! Jenni wuz here! I brushed a finger along the faded words, and carefully traced the scribbles one by one; mouthing each word in quiet incantation over and over until eventually, my tears dried out and the only heart left beating was my own.

Outside, the weekend janitor mowed away at a stubbly soccer field. Birds chirped. Kids played foursquare on the blacktop. My stomach rumbled. I checked my jean pockets and found 50₵. Enough for two Little Debbie Rolls from the gas station.

Read More