By. Laura Read

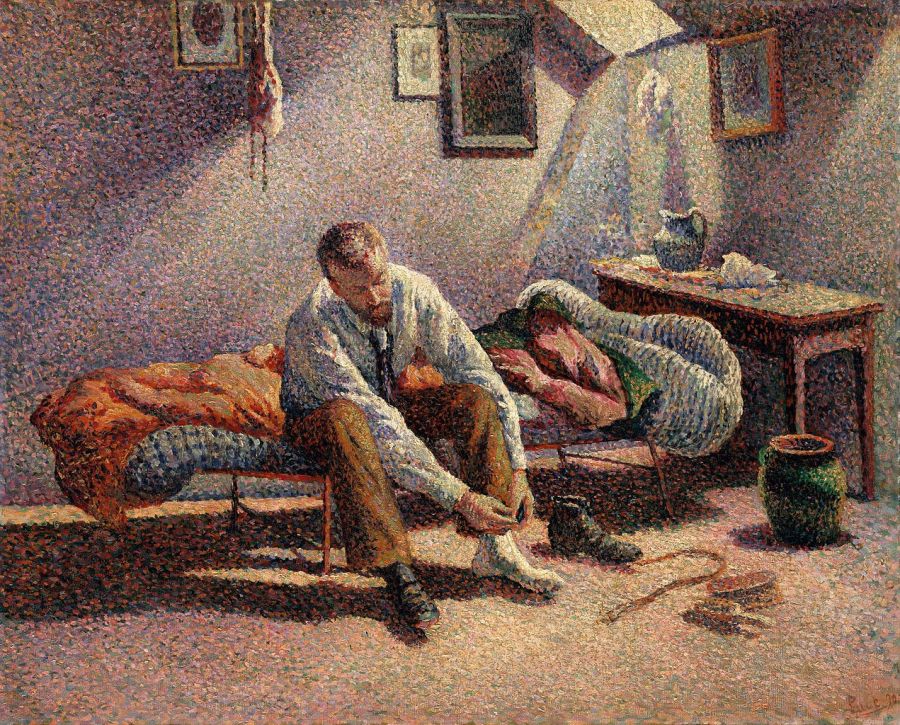

In the paper you can see the red booths

turned on their sides, their stuffing

leaking out. The fire spread next door

to the Milk Bottle, which is shaped like one

so you think of the bottles that clinked

on the porch in the first blue light

of morning, at the end of milkmen,

at the beginning of your life.

I went there once with a boy too sweet

for desire, after the Ferris Wheel

and The Octopus and trying not

to throw up on the grass and trying

to be sweet too, the kind of girl

you want to win a stuffed bear for,

one of the big ones that she’ll have trouble

carrying, so you keep handing

the skinny man your dollars and his eyes

glint and you wonder what he’s thinking

when he folds them in his pocket,

where he’s going when he gets off,

not the Milk Bottle for scoops of vanilla

in small glass bowls. His heart is a book

of matches, his mind clear as the sky

in the morning when it’s covered its stars

with light. In the winter, he’ll hang

a ragged coat from his collarbone.

He’ll think only of this year, this cup

of coffee, as he sits alone in his red booth.

If he walks along a bridge,

he might jump. And the river will feel

cold at first but then like kindness.

Last night a boy named Travis

killed himself

like young people sometimes do.

He told people he would do it.

They tried to stop him.

Now he’ll have a full page in the yearbook,

his senior picture where he’s wearing

his dark blue jeans and sweater vest,

leaned up against the trunk of a tree.

I wonder if he felt the bark

pressed against him

when he had to keep staring into the lens,

his cheeks taut from trying.

I wonder if he thought about the tree,

how could it keep standing there

without speaking,

storing all those years in its core.

Laura Read has published poems in a variety of journals, most recently in Rattle, Mississippi Review, and Bellingham Review. Her chapbook, The Chewbacca on Hollywood Boulevard Reminds Me of You, was the 2010 winner of the Floating Bridge Chapbook Award, and her collection, Instructions for My Mother’s Funeral, was the 2011 winner of the AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry and will be published this fall by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Originally appeared in NOR 12.