Midnight Snack with Leon

By Darren Morris

Featured Art: by nrd

I ran into the boxer Leon Spinks in 1992.

Spinks had won the heavyweight belt 14 years before

from Muhammad Ali. He had also won bronze

in the Olympics and gone to the penitentiary

for possession. By the time he got to me

he was all done with fame and fortune.

But he still scrapped with life, just trying to be.

At that time, I was staying with my brother

in Springfield, Missouri. He ran a pool hall

and kept an apartment in back of the place.

I snuck into the kitchen late one night for a slice

of that industrial orange cheese that I was

addicted to. I flipped on a light and

there was a large man sleeping on a cot

in the middle of the white-tiled room. But

I went ahead and opened the fridge because

when you are visiting someone, nothing is

unusual. It should all be that way, every day,

everything new, but it rarely is. I reached in and

lifted out a long orange sleeve. That’s when

the sleeping man said, “Leon hungry,” and instantly

I remembered my brother telling me that Spinks

had started coming into the bar, but I did not

believe him. It had been so matter-of-fact

that I barely retained the anchor to the info.

I made sloppy towers of tomato and cheese

sandwiches for Spinks and me and we ate them

in silence except for all the tooth-sucking

that bread and cheese promoted, especially

for Spinks who had more than a few teeth missing.

I cleaned up and Spinks lay back down. There

was nothing really to say. But when I turned off

the light, as if still a boy, Spinks said, Nigh-night.

They call it American cheese because it is processed

from nothing much. In 1978, Ali taunted him

and Leon beat his ass in one of the biggest upsets ever.

I met a ton of people back then who ceased to matter.

But that did not stop them and they persisted.

Read More

Just Say No

By Kelly Michels

Featured Art: by Feliphe Schiarolli

We didn’t say a word when the officer visited our classroom.

We didn’t pass a note or mumble, didn’t blink when the TV

flickered on, when the stats, wrapped in white, settled

on the screen. We didn’t dare color outside the lines

of the worry-eyed cartoon character buying weed from a teenage

bully or the gang of stick figures shouting in the margins.

We pretended not to see each other,

not to know the smell of bong smoke, late at night,

how it would drift through the air vents with their

laughter, how it would rise in a fog as we slept.

We pretended not to flinch when the egg hit the pan,

the yolk thundering against the cladded aluminum,

or when the officer pointed to the display of syringes

on the screen, the scenes of cherubic teens

snorting a line for the first time, the background darkening,

their eyes, lifeless, because the result is death,

the officer said, while pointing to a photo of a casket.

We pretended not to know how the dead could rise,

how they rose each morning to put away our cereal boxes

and make our beds, how they were waiting for us now

in their long white robes smeared with peanut butter

and hair dye, their tired bodies floating across the pearly

linoleum floors, the bones in their fingers thrumming

the edge of the kitchen sink to the sound of Clarence Clemons

in their heads, “The Promised Land” rising like a dark cloud

from the desert floor, their eyes lost in the throbbing

autumnal light, the snaking of branches across

the kitchen window, the tick-tock of the wind against

the leaves, how it feels like eternity, as they watch

for the bus, the broken ice maker buzzing,

the dishwasher rumbling, milk parting their burned coffee,

waiting for their children to return to them

to wipe their small skulls clean.

Read More

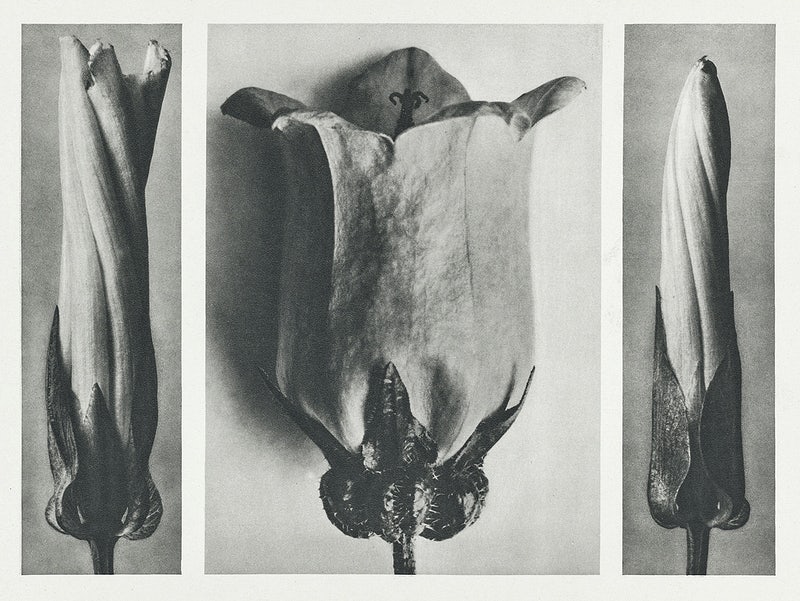

Coronation with Plastic Flowers

By Kelly Michels

Featured Art: by Karl Blossfeldt

She says it feels like flowers blooming in her veins.

The lilies watch her, unmoved

in the window.

She becomes the petals’

white polyester sheen, its rigid spine, slumped posture

leaning against the rim

of an old coffee mug filled with week-old cigarette butts.

This is how

I will remember her: bottles of pills, the walls scumbled

yellow, a flower blooming

in her veins, her gray breath rising

in a haze thirty years ago

the way she placed each plastic flower away from

the sun, the sting, anything

that could touch the color of the petal as if the light

could drag each one into the white,

worn sky, make it fade before her eyes. What else is beauty for?

but to be spun, set on a window sill

curtains drawn, petals hugged in dust, as she slept,

no sun to tell her if it was day or night,

the three of us kids trying to keep still, feeling our way

through the dark dreamt room,

unable to understand that this was the tick-tock of time.

This was what it meant

to live forever.

Only nothing lives forever.

The perfect moment—

the gardenias in full bloom

chatter staggering through a promenade,

the quivering flit of sparrows chasing

the listless light of noon

until suddenly even this ends,

until suddenly a car alarm ruins everything,

the chatter dissolves into people

screaming over each other,

birds fleeing, the owner trying to turn the damn thing off.

Maybe there were too many moments

that could never stay quiet or whole in her hands

like the day we took

our first steps, said our first words, or the day

she fell in love,

slept all night in his open arms, dreamt of the way

he looked at her as the ocean

wind tossed her floral dress,

dreamt of the way time could stop,

only to wake up and find every living thing

changed in some way

everything except

the flowers in her hands.

Read More

At the Edge of Everything

By Traci Skuce

Featured Art: by Alex Pasarelu

For the past hour, Alli had been sitting against the small oak, her eighteen-month-old son latched to her breast. His molars had finally—thank God— broken through, and now he suckled, cheeks sticky and eyes lolling with pleasure. Alli had hoped another mom would show up. Jeannie was off visiting her parents in Vancouver and Clay, well he was just plain off, so she hadn’t had an adult conversation in days. She wanted someone, anyone, to gab with about the impossibility of lost sleep, errant husbands, and teething. But there were only the crows, waddling around the rim of a garbage can, diving in for pizza crusts then flying off across the playground to the giant cedar.

Alli’s daughter, Tavia, looked at the birds from under her floppy sunhat, and then dumped a handful of sand onto an accumulating pile, patted it down. Alli mimed eating, mumbled yum-yum as she had been since they’d arrived. “Do you like it Mommy?” Without waiting for an answer, Tavia ran back to the production center beneath the slide.

Jack continued suckling. Both breasts were drained and she’d become a giant pacifier. His eyelids fluttered and his blond feathery hair stuck to his forehead, ear crusted with milk and peanut butter. She picked at it, and he swatted her, still sucking hard. Enjoy them while they’re young, people said, but she couldn’t wait to toss these days onto the slag heap of motherhood.

Cousin Scott on Food Stamps

By Anders Carlson-Wee

Featured Art: ‘The Thirty-Six Star Flag of the United States of America’ by unknown

—in memory of Scott Christopher Maxwell

1961–2007

First thing is, I got as much right to get my foodstamps

as the next man. Second thing is, what I make of em

is my own Han Solo. State aint got no right

comin around sniffin halfway up my ass, tryin to catch

some little whiff of a goddamn infringement.

If I wanna fetch my breakfast with em, fine,

let a cowboy fry his bacon. If I wanna sell em for cash

or trade em for dope, that’s my own Han Solo.

You think I’m gettin rich outta this?

You think I’m puttin some greenbacks away someplace?

Saint me somebody if I’m flush in more than bellybutton lint.

And anyways I’m only sellin em to veterans.

That’s the third thing. A lotta vets can’t even get

no foodstamps, and you mind tellin me why?

You think them boys went off and lost a leg

in Iraq or some other ass crack of the planet

just to come back home to trade me a dime-sack

and some percocet? What? So they can hobble

their broke ass down to Deals Only and garner themselves

with nothin but a stone cold bite of somethin to eat?

You tell me. Me, I don’t even wanna guess.

And the other thing is, what’s the difference

if I got two-three a them food cards?

Who am I hurtin? I’m askin you––who am I hurtin?

And I know right off what you’re gonna lay on me.

You think I’m reachin in and stealin them tax dollars

right out your own privately owned ass crack.

But the thing is, I aint got your goddamn tax dollars.

Where you think all them sorry ass one-legged vets

is comin back from? Disneyland?

War aint the Lord’s plan, I can tell you that much.

Course, neither is foodstamps. Lord’s got two hands

and he aint askin for handouts with neither of em.

And you can bet your whole hard-on

he aint givin em away neither. That’s why I stopped

prayin. Lord aint givin and Lord aint takin.

Lord’s reachin out same way a tree reaches.

Real slow and easy. Sorta callin you in

without callin, cept maybe with the wind.

And your job’s as simple as goin to him, cause you’re lost

and you know it. And that’s the same shake

them vets was expectin to get when they come back

one-legged, but they didn’t get that, did they?

No they didn’t. Got percocet. And they’ll be dosin that shit

till the day they’re dead. What’s that old sayin?

Send me home in my casket. Well, tell you what,

the minute I’ve gone and dropped off dead

and been laid to rest, you got my god’s honest say-so

to bust open my casket and stick a straw

up my ass and suck and see if you find any flavors

that taste just even a little bit like your goddamn tax dollars.

Read More

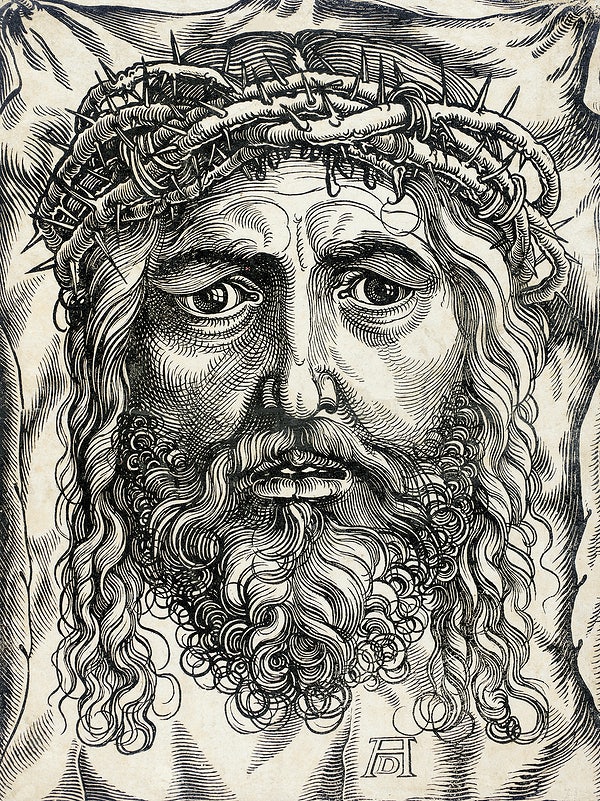

Last Seen on a Milk Carton

By Reese Conner

Featured Art: by Sebald Beham

In the photo on the left, the first Jesus poses

with a thorny crown scratching his skull

and his right arm slung around the cross

as if he and the cross are friends

or first-time prom dates,

while his mane, miraculous, immaculately

tumbles to his shoulders

in loose curlicues, the bounce of which

you can easily imagine

though scarcely believe

considering the dry, desert air,

and his skin (that skin!) is a goldilocks-bronze,

is light enough

not to alarm the whites

is dark enough

not to alarm the historians,

and his eyes are trustworthy

and inevitable—you don’t get to say

you’re the son of God

with any old eyes, no,

they need to be

more lamblike than lifelike—

meanwhile, in the photo on the right,

the second Jesus, age-progressed

two millennia since he went missing,

is a skeletal heap. And you begin to think

how sad it must be

that they keep looking for him.

Read More

The Resort

By Preston Martin

He paces, half naked,

across his second-floor balcony,

phone against his ear.

A translucent mist moves on shore,

the swoosh of high tide hardly heard

across mannered dunes.

As the day moon hangs

over his building fresh sunlight sinks

low in the moist air like a lemon slice in soda,

sparkling dewy marigolds, dollar weeds.

The man paces, turns, punctuates

thoughts with a free hand, either

pleading or singing into the phone.

Please

let it be to an old love,

who loved him on this beach, loved him once,

on a tender morning like this morning.

Still now, he stares at the phone,

as if it were sentient, caring,

as if the conversation still goes on,

as if the greater part of life

isn’t our suitcase of memories,

handled everywhere,

the calling back

of times slipped through fingers,

the calling back

what can’t come back.

Read More

Sneakers

By Patrick Crerand

Featured Art: ‘blue sneakers’

My father never exercised. He chased me upstairs after a fresh word at the dinner table once or twice—quick sprints that ended with a face-slap photo finish—but no trips to the gym, hardly even a ball game on TV. On weekends, he wore sneakers—not tennis shoes—always sneakers, as if that’s what one did to hide silently from the world of sport.

But that day—my sixth birthday—after he made the cake and gave me the Frisbee, he said to my surprise, “Let’s see if it spins.” I was out the door in the backyard before he had laced up the first shoe. Neither one of us was very good, but there we stood, spinning the bee in front of the sugar snap peas he had planted, when we heard Aaron, the boy next door, scream in a high, inhuman pitch—a cartoonish noise I thought only diving eagles made, or the ricochet of bullets in old westerns. I almost laughed. My father knew better. He straightened and ran toward Aaron in the side yard between the houses. He leapt over the chainlink gate with a quick hop, following behind the crying boy until he caught him by the arm and saw where Aaron was pointing. “What?” my father asked.

“My sister,” Aaron screamed.

Read More

Detective Story

By James Lineberger

Featured Art: by sir Edwin Landseer

When I worked as a janitor at the courthouse

I met a detective in the Sheriff’s department

whose son, I learned, had committed suicide

some months earlier. Having lost a son myself

in a car-train collision, I tried to offer my condolences.

“Your boy kill himself?” the detective asked bluntly.

“We never knew,” I replied. The detective grunted

noncommittally and opened his desk drawer to take out

a photo of his son, a young man in his twenties, kneeling

and embracing a dog as he grinned for the camera.

“Two days before it happened,” the detective said.

“About the same age as our son,” I said.

The detective stared at the photo for a moment.

“You got a dog?” he asked.

“Two,” I said.

“Thing about a dog,” he said, “a person can screw up

a hundred ways, and his dog will love him when he can’t

even love his self.”

“Our son’s dog still sleeps at the foot of his bed,” I said.

The detective turned the photograph over on its face

and glanced up at me, his eyes as cold as stars.

“Ain’t his dog,” he said. “It’s mine.”

Read More

Sunny Day

By Joyce Schmid

Featured Art: ‘Woman Lying in the Dunes near Noordwijk’ Jan Toorop

Verweile doch, du bist so schön.

—Goethe

I grab the young, unruly day

and say, Stand still, stand still.

I want to comb her hair and dress her up,

but she just laughs and wriggles in my grasp

and breaks away. She dances mockingly,

just out of reach, the little imp,

and runs ahead of me. I’m running

out of energy to try

to catch her in my arms,

warm, fragrant child,

her changeling eyes lit up

with winter sun.

Come here, you darling day,

and stay with me

a while, a little while.

Read More

Of Course Death

By Roy Mash

Of course death is on its way,

and life’s a blink,

and yes the unexamined one sucks,

and doubtless

we’re well-advised, periodically,

to expose ourselves

to the nuisance of these truths,

waggling their

fingers with their thumbs in

their ears, ever

heckling us with the raspberry

of our mortality.

Still, we cannot carpe every diem,

squeegee the universe

of each last moment, shovel our

noses 24/7 into

the coffee or the roses or

what-have-you.

Virgin-bedding stratagems aside,

some days, maybe

even most days, the unforgiving

minute’s happy

just to be left alone, frittered

on some dopey

soap opera, or stewing over

a parking ticket.

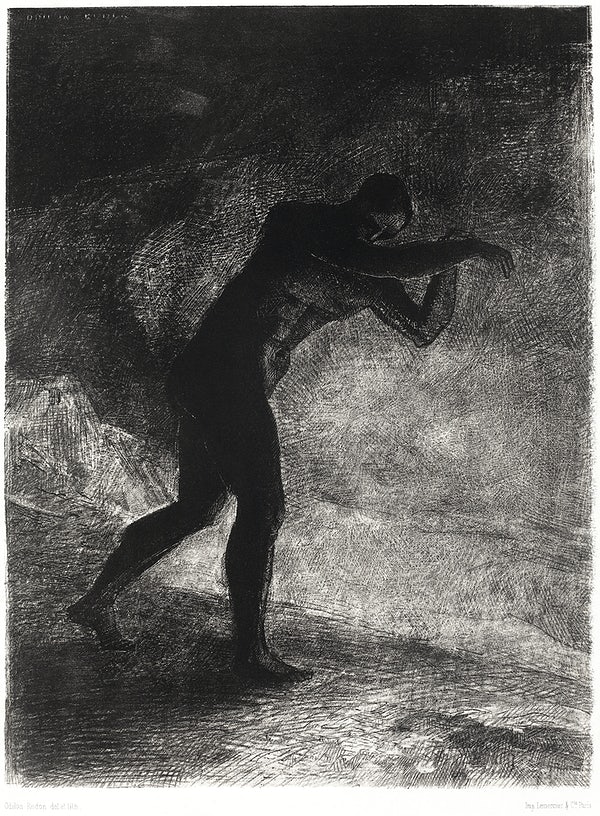

On Being Asked to Contribute to the Villains Feature

By Richard Cecil

Featured Art: by Odilon Redon

I searched ten years of word files looking for

titles with names of politicians who

enrich the rich while trampling down the poor

and corporate criminal CEOs who screw

employees out of wages, rape the Earth,

and hide their stolen billions far offshore,

and drew a blank. I also found a dearth

of killer clowns and warlords steeped in gore,

religious rabble rousers, nasty nuns,

child-abusing Catholic priests—zero.

No bought congressmen who vote pro-gun;

no homicidal patriotic heroes.

What’s blinded me to monsters all those years?

The Frankenstein inside. It’s him I fear.

Read More

Villainous Villanelle

By Denise Duhamel

My id spits and licks his lips, trips my conscience,

my ego, Miss Goody Two Shoes.

Her neon pink laces make him nauseous.

My ego finds my id monstrous—

His red face is bulbous. He reeks of booze

as he spits and licks his lips, trips my conscience

and my allegiance is split. My id’s obnoxious,

full of tattoos, a shower long overdue.

But my ego’s pink laces make me nauseous.

My ego and id live in a province

of my psyche, battling to be my muse.

My id spits and licks his lips, trips my conscience.

He tells me evil is the only constant,

that villains are cool. Who needs society’s rules?

My neon pink laces make him nauseous.

I go to a shrink to check my noggin.

Her pantsuit is blue. Her couch is chartreuse.

I spit and lick my lips. She trips my subconscious.

Her neon pink briefcase makes me nauseous.

Read More

Milton’s Satan and the Grammar of Evil

By Kimberly Johnson

In the long tradition of literary villains, no figure towers with such gleeful, scene- chomping menace as the character of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Satan the arch-fiend, the über-villain, elaborated out of the bare-bones narrative of Genesis by New Testament writers into a primeval malevolence that Milton combined with epically heroic qualities. Satan the dauntless, who in the first book of Milton’s opus strides imperiously across the lake of burning marl, rallying his vanquished followers to a brave resurgence against God’s favorite creation. Satan the guileful, who seduces Eve into humanity’s “First Disobedience” (1.1). The plot of Paradise Lost offers plenty of opportunity for Satan to scheme, beguile, attack, and otherwise subvert the designs of Milton’s God. But I’d suggest that such narrative exploits are mere caricatures of evil, and distract from Satan’s most damnable offense, which inheres not in any particular action in his own interest or against God’s. Rather, Satan falls under the text’s greatest condemnation for his refusal to act as a morally self-determined agent. In Milton’s poem, Satan exposes his deepest villainy in his denial of his own agency.

Rather than looking to some episode of valor or vaunting on Satan’s part, in order to suss out Satan’s particular brand of indolent evil in Paradise Lost we can alight with him atop Mount Niphates, where he perches at the outset of Book 4 and delivers a monologue. Unobserved by either loyal minions or intended dupes, Satan mutters his words to himself without thought of being overheard, thus introducing into the midst of this headlong and familiar tale of the Fall a moment of lyric dilation. Time suspends, plot events pause, and Satan reveals his tragic flaw not in his actions but in his language. He begins with an apostrophe to the unresponsive sun,

Read MoreThe Pleasure of Browning’s Villains

By Robert Cording

As an undergraduate in a state college, I read an essay by Howard Moss, a poet I admired and the poetry editor of The New Yorker at that time. Though his advice was of the usual “learn the tradition” school, what Moss said about writing poems struck my insecure hyperconscious-of my-poorly-educated self hard—he said, unless a poet knew the poems of the past, that poet was bound to repeat what another poet had already done better. Solid, but obvious advice that, nevertheless, I took deeply to heart. And so I went off to graduate school in English in 1972, closeting, like many of my fellow graduate students, my desire to be a writer inside the more mainline pursuit of a doctoral degree. In an early Victorian literature class, I first read Robert Browning. I was writing persona poems, trying to find my own voice by assuming the guise of others. Struck by the energy of Browning’s dramatic monologues, I began to think about the way he appropriated first-person narration and about the way his poems worked dramatically, through their plots.

His “villains,” in poems such as “Porphyria’s Lover,” “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church,” and the more famous, possessively titled, “My Last Duchess,” all employed untrustworthy first-person speakers that were allowed to convict themselves. And, while Browning was clearly concerned with the immorality of villainy, his aim was modern in so far as these were poems of the “act of the mind,” as Wallace Stevens would later define modern poetry. They were not about ideas of pride and envy, or possessiveness and the love of material things, but about the reader’s experience of the villainy at the heart of them. Or to put it another way, the reader’s experience of the speaking voice, a voice that created, as it went on talking, a kind of internal, if perverted, order within the fictional entity of the poem.

The Villain Who Shut Down an Epic

By Jeanne Murray Walker

Recently, as I was on the way back from our usual early morning at the gym, I told my husband that the editors of New Ohio Review had asked me to write a piece about a villain in a poem.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Well, it’s interesting, don’t you think, that poems might have villains? Like murder mysteries?”

“Oh, I get it,” he said. “In Robert Frost’s ‘Mending Wall,’ the villain is the wall.”

“No.” I laughed. After all, how can a wall be a villain? I had been thinking of narratives like The Odyssey and “My Last Duchess.”

But when I re-read Frost’s lyric, I saw what my husband meant. It is the power of evil, both the shadows of the trees and darkness of the heart, that builds and maintains the wall between Frost and his neighbor. I began to feel deeply curious: What can we learn from watching villains in poetry?

Maker and Prophet: Frank Bidart and the Mask of “Herbert White”

By Mario Chard

Looking at Frank Bidart’s “Herbert White” always horrifies. The art is extreme, a mode Bidart has suggested he prefers. And why? Because he gives voice to a monster, the worst kind, a necrophiliac, a rapist and murderer of young girls. And because White’s voice is at once human, demotic, stupid even (“What the shit?”), and elevated (“how I wanted to see beneath it, cut // beneath it, and make it / somehow, come alive”), often shifting our attention the way a character’s voice can when it suddenly turns to eloquence, we get the sense of another meaning behind the words themselves, another presence.

Framed in dramatic monologue, the poem follows the associative movements of Herbert White’s mind as he recalls his murders and victims, his return to their “discomposed” bodies, his childhood forays into torture and rape, his anger in adulthood at his father for “sleeping around” and starting a new family. Above all, we are witness to White’s clawing through his mind to make us “see” and understand how “beautiful” his crimes have appeared to him, to go back to those moments when he could “feel things make sense” before his guilt would force his mind to “blur” and trick him into believing that “somebody else did it, some bastard / had hurt a little girl.” Reeling at his straightforward confessions, we forget or ignore that everything White admits is spoken in the past tense until the only line alluding to his current state of mind appears near the end and shocks us with the revelation that his guilt has finally won out, that he is burning in a consciousness of his own sins: “I hope I fry.”

The Unredeemed Villain?: Ai’s “Child Beater”

By Denise Duhamel

So often we are drawn to literary villains because of our shadow selves, parts of us so ugly, selfish, or antisocial we repress them. Sometimes we even find ourselves rooting for the villain—if we can’t be the heroes, we can at least find release in cackling along with Captain Hook, Tom Ripley, Hannibal Lecter, or the Joker. And we often can’t help but identify with those villains who are written with empathy and complexity.

In most novels, comic books, or films this villain will be conquered, suppressed, or will enjoy a narrow escape that makes us feel both excited and ill-at- ease. In a sequel, the hero or heroine will battle this villain again, a rematch that seems psychologically true as we recognize the cycles of evil around us.

But how do we negotiate a villain who acts with impunity, with no heroine on the way to save the injured party? How do we negotiate a villain in a poem that has no sequel or counterpart? How do we negotiate a villain in a poem that offers no rescue, just an emboldened perpetrator?

Villains of Confessionalism

By Kathryn Nuernberger

William Blake, reflecting on how much readers tend to prefer that old villainous anti-hero Satan to any of the good guys in Paradise Lost, remarked, “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

Certainly there are no shortages of ways to be a villain, but poets, freed as they are from the constraints of “plot” are also freed from the narrow alleyways of that first-order definition for villain, “character whose evil actions or motives are important to the plot.” Instead, we, or the speakers we inhabit, can be villainously “responsible for trouble” or “causing of harm” or “sources of damage.” To that end, Confessionalism is a genre of poetry that offers unique opportunities for inventions in villainy, dragging vices like wrath or pride into grayer terrain, or maybe even, in some cases, the light.

There is, famously, that time Robert Lowell quoted directly and without permission from the pleading letters his soon-to-be-ex-wife, the writer Elizabeth Hardwick, sent asking him to leave off his affair and return to her and their daughter. Or the times Sylvia Plath excoriates one aspect of an oppressive hegemony—its condescending patriarchy—while propping up its racism and antisemitism through thoughtless metaphorical appropriations. Oh, but they don’t mean to do it exactly, which makes their villainy so much more—well, let’s just say it’s no party, the devil’s or otherwise, this work we the living do of dragging our ancestors to confession. For this essay I propose instead a jubilee of recent confessional poets who have learned from these examples how to create on purpose speakers who are troublesome, reckless, dangerous, and careening. They make an art of it—these infernal confessions—and I can’t get enough of such raw lyric villainy.

“Guilt Is Magical”: Adultery as Poetic Villainy

By Catherine Pierce

The best villains—or at least the most compelling—are those who own their villainy, and, in owning it, reckon with it. And the most compelling poems tend to be those that do the same kind of reckoning; as Yeats famously wrote, “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.”

Adultery is, certainly, one of the quieter types of villainy—not nearly as flashy as murder, bank robbery, or comic-book citywide destruction—but also, like all domestic villainies, far more commonplace, and insidious precisely because of that. It’s no surprise, given poetry’s historical attraction to passion, high drama, romance, and regret, that the genre is lousy, so to speak, with cheaters and homewreckers quarrelling with themselves all the way to revelation.

New Ohio Review Issue 20 (Originally printed Fall 2016)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

New Ohio Review Issue 20 (Originally printed Fall 2016)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

Issue 20 compiled by Alli Mancz.

How to Survive on Land

By Joy Baglio

Featured Art: Playful Mermaid by Henri Héran, 1897

Let me tell you about my mother, a mermaid: For years, despite her handicaps, she embraced land life in Okanogan, Washington—the drizzly winters and sun-soaked summers—with a steadfastness both impressive and exhausting. She read us stories with the ardor of a human mother; bagged our lunches; brushed our hair. For years, she was just Mom: Mom who snuggled up to us on the couch with a book; Mom who packed Tupperware containers full of watermelon and whisked us away to the town pool on humid summer days; Mom who cooked themed meals (Tuna Tuesdays, Waffle Wednesdays); Mom with her perpetual ocean smell and unruly laughter. Of course, there were harmless omens of her first loyalties: shellfish for breakfast, kelp pods strewn like confetti around our living room, the shrill whale-speak whines that filled our house in the mornings, our Nereid names and Mom’s insistence that my sister Thetis and I explain to every curious land-dweller our sea-nymph heritage. (My name, Amphitrite, means Queen of the Ocean, after all.)

Read More

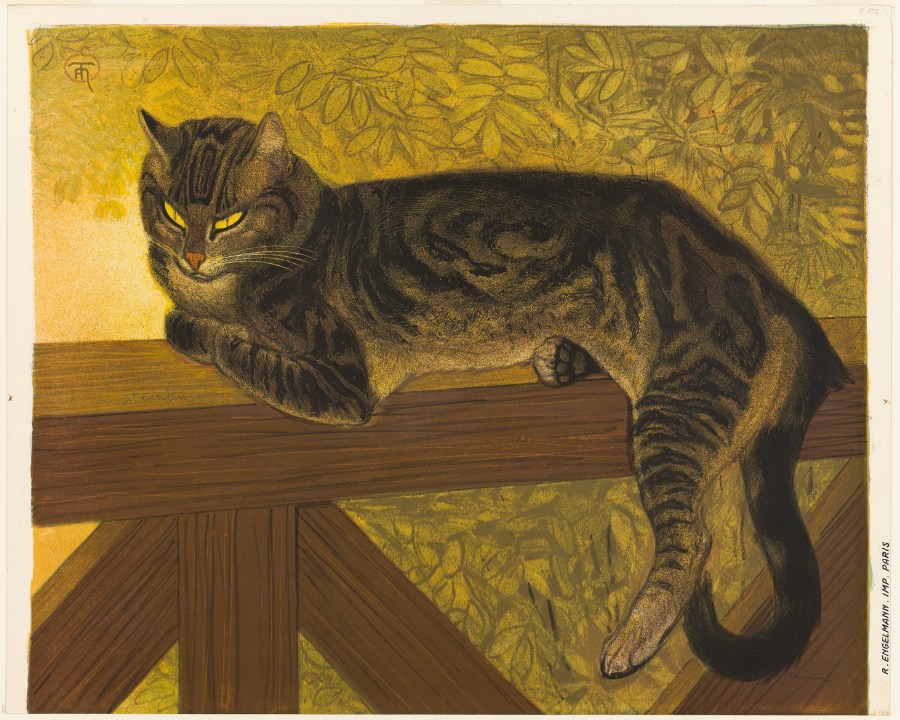

Bobcat

By Andrew Cox

Featured Art: Summer: Cat on a Balustrade by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, 1909

–For Jerry Lee (1934-2016)

There are bobcats in the neighborhood

Said the woman in the decked-out SUV

Do you have a whistle

As I walked off my grief in Texas

Where I came to see my mother die

And when I saw the bobcat

Come from the drainage system

And stare at me with black pupils

Drilling into those yellow eyes

I knew it wanted me to sit down and listen

Love your mother the bobcat asked

Not enough I said

I could have visited more

It said man hands on misery to man

One of your kind wrote that I think

Yes I said the poem is never enough

And neither are the sentences it hissed

They fail in situations like this

Yes I said punctuation doesn’t help

Nothing helps

Remember the bobcat said

You are no longer a son

You had one shot and the pistol is empty

I understand I said though I did not want to

I have two hearts it said

The one they will find when they cut me open

And the one I use to live forever

Think about that

Think about that face those hands her eyes

And it disappeared down the slit

Now I knew where my mother was

In the bobcat’s second heart

The one it uses when it growls into the night

And puts everything in its place

That face those hands her eyes

On the hunt until dawn

Only ready to sleep

When the rest of us are ready to wake

Read More

New Ohio Review Issue 20 (Originally printed Fall 2016)

Newohioreview.org is archiving previous editions as they originally appeared. We are pairing the pieces with curated art work, as well as select audio recordings. In collaboration with our past contributors, we are happy to (re)-present this outstanding work.

Reno Redux

By Ansie Baird

Featured Art: Man holding a horse by the bridle by Dirck Stoop

My father flew to Reno, Nevada, sixty

solemn years ago to sue for a divorce.

I had no idea where Nevada was or

why my parents were divorcing.

In the mail arrived a shiny photograph,

my father sitting tall on a horse.

I had no idea he knew how to ride.

He carried a rifle across his lap and

on his head he’d set a cowboy hat.

He was smiling like all-get-out.

I had no idea what there was to smile about.

He stayed away six weeks, at some

dude ranch where rattlesnakes curled

and lurked in the underbrush. I lived

in a cluttered city house without

rattlesnakes or a father. My mother

packed up all our winter coats and boots

and sold the house. We moved into a flat.

After that, everything was touch-and-go.

Reno was a place I planned to boycott.

Sixty years later, I’m at the Reno airport

waiting for a connection,

uncertain when it’s taking off.

All of us seem to be divorced.

Slot machines clack at my elbow,

crowds of men in cowboy hats lurk

in plush corridors, looking like they

might be someone’s father.

Read More

Chino, California

By Darla Himeles

Two crows claw down to cement

between the outer and inner fences—

beaks like swords, backs slick,

slashing wings and talons.

I watch them fight from my car today

as I watched my parents as a child: clutching

a book in my lap. I cannot read

the crows or my father, for whom I wait

in my locked car, his bag of belongings

in the back seat beside the maps I printed

to find him. At once, a line cuts

from one building to another: orange

jumpsuits shocking under smoggy, industrial sky.

I pinch my lip, examine their faces, their gaits.

Not my father, not my father—maybe? No,

not my father.

Hours pass, the crows disperse.

The prison yard empties.

Two hours after the designated release, a small

group of men gathers at the gate.

Escorted by officers, they wear stiff beige chinos,

white canvas loafers, and baggy T-shirts

to greet the other side. I see him

shaking his gray head to an officer, No,

there’s nobody here for me—must be a mistake—

Sir, I need the bus fare promised me.

Read More

Certain Things

By David Brendan Hopes

Featured Art: Tinker with His Tools by Camille Pissarro, 1874/76

For the sake of my father, certain things

must be done in a certain way:

tightening of bolts, of nuts around threads;

coiling of hoses; firm, instant replacement of lids;

spreading of seed from the hand held just so,

in furrows dug to the joint or the knuckle, depending;

wash it when you use it, never put it up wet;

don’t be opening and closing the screen door

as if you were a cat.

Be grateful for a job, a meal, a leg up.

All that.

In the seasons set aside for such emotions,

of course I hated him.

All things, even hatred, wear away.

In the season set aside I became him,

doing what he did in the way he did it,

hiding the injured heart the way he hid it.

Waking so many hours before full day

from the dream

that something certain’s gone astray.

Read More

She-Monster Gets Fired

By Kim Farrar

Here you are again, running from the villagers

with their torches and pitchforks. You thought

you finally fit in. You filed down

your neck-bolts, got rid of your high-waters.

You watched Oprah, kept a dream diary,

a gratitude journal, pictures of your thinner self

on the fridge. You tried to keep your need

for electricity minimized: licking the outlets,

rubbing your hair with a balloon for just a crackle.

You knew it would happen. Every morning—

the affirmations, the meditation, the positive thinking.

You longed for lightning and rain.

You did everything right to escape

the old ways of staring into the well.

It took years of practicing the right laugh.

You did your best. Married up.

Got a job teaching ESL. Now and then,

a grunt would slip and

crickets crickets crickets.

People liked you. You were funny.

But one day you found refuge

eating flies in the faculty lounge;

soon you stopped hiding

your green undertones with foundation.

You missed being the girl

who loved her square head,

touched her thick-stitched scars like Braille.

The villagers yell, Kill her! Kill the monster!

You’re barreling through the woods,

nettle whips your ankles as you soar

over logs in your clodhoppers.

You’re filled with the old familiar joy

of being free and incredible.

Read More

Why It’s Hard to Write About My Brother

By Kim Farrar

Because he called me numbnut

now no one calls me numbnut

Because in therapy I learned the word infantilize

and stopped asking him if he was all right

Because I want to recite the titles of his paperbacks instead

Dune Silent Spring Slaughterhouse-Five

Because he showed me how to give the finger when I was six

and then I showed Mom

Because I listened to him curse in the bathroom

after Dad buzz-cut his hair

Because at 54 he could still bruise the same spot

with a knuckle-punch

Because we discussed the etymology of kerfuffle

but never mentioned emphysema

Because the last time he lit a Marlboro to rest

I joined him

Because he taught me Sudoku

but said he couldn’t help with counting to ten

Because they took him away in a midnight body bag

Because he could pinch open the beak of a baby robin

to feed it drops of milk

Because he once touched me and I cooperated

Because to wreck cars, to drive drunk, was a form of apology

for being a disappointing son

Because he comforted my worry that his tetras were bored

They have no memory, numbnut,

each swim back is a new ocean

and then I envied them

Because his longest relationship was with a club-footed lovebird

Because I’d ask about the impossible physics

of the hummingbird’s flight to spin the conversation

away from troubles

Because he said I couldn’t get good at Sudoku

because he had to beat me at something

Because he drove me around the city

to point out the cement he’d poured,

the flagpole at the post office, the Kroger’s sidewalk

Because he said the one thing he liked about the job

was leaving something permanent

Because his ashes are in a box and I worry about moisture

Because our last day together at Newport Aquarium

we watched sharks swimming overhead

Because he would withdraw for months

but I left messages anyway

Because he loved my dream of him

Read More

At the Threshold

By Marilyn Abildskov

Featured Art: Dilapidated House, 1811

She hesitates, then opens the unlocked door. The house is not hers. It’s nobody’s yet. That’s why she’s here. To walk on red tiles in the empty entryway. To see if there’s carpet yet in the bedrooms. To touch the smooth white marble fireplace that reaches the ceiling in the living room. To wander empty rooms before the rooms are filled.

Here in the entranceway of the new empty house she says out loud—hello hello—and listens for something, a spirit maybe, to say something back.

Nothing. Not even an echo.

From the kitchen window, she can see her home, the tip of a modernist triangle roof. In the distance, she can hear her mother playing the piano, lost in the music. Her shoes squeak against the floorboards of the hallway. No carpet. Not yet.

Read More

My Good Brother

By Young Smith

Featured Art: Two Boys Watching Schooners by Winslow Homer, 1880

If I had a brother, he would be called Enoch or Ephraim—

a name alive with the wisdom of some long forgotten past.

Though older than me, there would be no gray yet in his beard.

There would be no lines on his face, and his full hair—

not thinning yet, like mine—would be brown as the wings

of a thrush. He would whisper Roethke in his sleep,

my brother Ephraim or Enoch, and his poetry would lift

the weight of old bruises from my eyes. He would visit

our father’s grave and feel none of my dark anger there.

He would sing the dead man’s favorite songs, recalling

only his happiest hours. He would have learned to live gently,

my brother, and would teach me that secret with nothing more

than a nod or a warm arm across my shoulders. You, Enoch; you,

Ephraim—how I long for the cool press of your hand on the back

of my neck, my good brother, my quiet companion of cruel nights.

Read More

Here There Was a Stool with a Crippled Leg

By Young Smith

Featured Art: The Chair from The Raven by Édouard Manet, 1875

There are no ghosts in her rented house—

only the shadows of objects

removed by other tenants long ago.

Here there was a stool with a crippled leg,

here a bookshelf filled with fat Russian novels,

here an upright piano with wine-stained keys.

These furnishings have vanished, but their shapes continue—

like spots on the retina after looking at the sun . . .

Though she can find no path from one door

to the next where the shades of their sofas

don’t stand one within the other, of the former

tenants themselves, very little can be said . . .

The mirrors have collected the pale stories of their eyes,

but the glass is too crowded to tell them clearly—

yet even now, among the wraiths of hat trees

and recliners, where the dust of their voices

drifts like smoke along the baseboards,

she can often feel their sorrows, breathing

slowly in the corners, still alive

with a helpless longing to sleep.

Read More

Gorilla

By Young Smith

“Sullen” only begins to describe it—

his all too lucid, all too human stare.

His mate sits nursing an infant behind him

in the mouth of an artificial cave, while,

just to busy his hands, it seems, he strips

leaves from a twig of bamboo. His gestures

are slow and deliberate, but as his fingers work,

his eyes never leave us, moving in turn

from one face, from one camera to the next.

This, of course, is what holds us at the rail—

that he watches back, like no other animal

in the zoo—and there is only one way

to understand his expression: he has little

hope for the health of our souls.

Read More

Moksha

By Alexander Weinstein

Featured Art: Street at Saverne by James McNeill Whistler, 1858

I.

Rumor was you could still find enlightenment in Nepal, and for cheap. There were back rooms down the spider-webbed streets of Kathmandu where they wired you in, kicked on the generator, and sent data flowing through your brain for fifteen thousand rupees a session. It was true, Jeff from the coop had assured Abe, though passport control could be a bitch when you returned to the States.

“They pulled my buddy when we hit Newark,” Jeff had said, sipping maté from a gourd. “But he was showing. His third eye was completely open and he wanted to hug everyone. Just think about porn and you’ll be fine.” Jeff had handed Abe a crinkled business card. Namaste Imports. “Go to this place.”

So Abe had saved his money, bought the ticket, and traveled the endless hours, numbed by bad sleep and bland airline food, to find himself in Kathmandu. Finding Namaste Imports, however, had proved impossible. The streets had no names, and looking up, all Abe saw was a tangle of electrical wires and lights blinking on in the dusk. Around him, masses of tourists, heavy with backpacks and vacant looks, milled about. And amid all this churned a perpetual stream of cars and mopeds, nudging their way around pedestrians, honking, yelling out of windows, and raising endless dust. It all seemed far from enlightenment.

Read More

Bluebirds Are Cavity Nesters

By W. J. Herbert

Featured Art: Bird’s Nest and Ferns by Fidelia Bridges, 1863

Cement truck crushing stones

at 3 a.m. on a Flatbush side street?

No, must be the double bass player

grinding his seven-foot case along broken sidewalks,

as if inside his sarcophagus

whose fist-sized wheels are screaming

there’s a mummy dressed in lead,

and it’s so hot again my ceiling fan’s blade

is a soldier’s lame leg that is drooping

and each time he turns,

it drums on the inverted edge of the light bowl

while someone upstairs

drops the booted foot he just cut from a corpse,

but he keeps cutting and dropping,

cutting and dropping,

so it must be a dozen corpses, or

maybe it’s a frozen hen landing again and again,

as though my landlady’s niece, still drunk,

has made up a game in which you get ten points if,

when you drop it from the top of a ladder,

the hen lands on her severed neck.

I can’t sleep. Even if Sialia sialis

relies on dead trees for nest sites,

it’s smart enough to live deep away from the world.

Read More

Anniversary Gift

By Robert Cording

Featured Art: Peacock and Dragon by William Morris, 1878

After reading that hummingbirds

are so light eight of them can be mailed

for the price of a first-class stamp,

I close my eyes and see them, fully revived,

rising out of some envelope of old memories.

I’ll name them again as we once did

so long ago—Rufous, Anna’s, and Broad-tailed—

darting to and from the feeders, sipping,

then retreating, flying jewels

the Spanish called them, and now I recall

how one of the Anna’s, its garnet head

and throat glowing in the misted air,

hung like a jewel at your ear.

Here they are, or the memory of them.

Remember that trying-too-hard-to-be-hip

B&B in Telluride, a hot tub on the roof;

above the water, crisscrossing strings

decorated with Japanese lanterns

and four red heart-shaped feeders that brought

close the ebullience of the hummingbirds.

They surged around us, their kaleidoscope

of iridescent colors lightening

the cool, rainy day and helping us forget

the fogged-in, dim presence of the Rockies

we had come for and couldn’t see.

Curtained in the tub’s steaming air,

soon enough our eyes were in love

with birds we couldn’t stop looking at,

their scintillant existence drawing

jeweled lines we swore we could see.

Which is why I’m bringing back the past,

those tiny birds disappearing

into all the years behind us now,

but today returning all at once,

as if some blessing had been conferred

without my asking; and so

I offer them to you, hoping these words,

even though they dim the colors as they must,

will draw for you their sweet transport.

Read More

The Cave

By David Gullette

Coming back from Escamequita past the curve at the peak

there was the valley of Carrizal with its steep mountain rising above it.

What’s that up there? I asked. Looks like the entrance to a mine.

Oh, the old man said, That’s the Cueva de los Duendes.

I knew the word from Lorca’s great essay

but he meant some dark flamenco trance when strummed sheepguts

and a shout beyond reason jam in our ears the mesmerizing song of death.

Here in the back woods of Nicaragua it just means little people,

fairies, minor local deities, trolls, semi-domesticated goblins.

Or witches. Things that rustle the bushes after the moon rises

or borrowing feathers shriek in the sky above your chickens.

Why do I feel this perverse relief that something remains here

to challenge the cult of the soft Galilean and his stay-at-home Mom?

Some trace of the pre-Columbian, or something from the hills and caves

of Spain, smuggled in with the priests and horses?

Once I was in Yucatan: An afternoon storm was brewing

and when the thunder shook the limestone world

the Mayan lady at the kiosk looked up and said “Xac!”

The old god of lightning, rain, and fertility.

Remember how Wallace Stevens’ Crispin, hearing

a rumbling west of Mexico fled, and knelt in the cathedral

with the rest? The thunder unleashed a self possessing him,

some quintessential fact that was, he says, not in him in Connecticut.

My idle thought passing through Carrizal was to find a way to climb the hill,

enter the giant portal of the cave, probe the interior with my LED.

But “to know a thing is to kill it,” says Lawrence,

and I’m too old to court more disenchantment,

so back to town: a little rum, check the banality of the Internet,

news of winter’s vacancy back in Boston, a little European music

to sprinkle on the sizzling red snapper . . . How easy to live it,

this our minimal unhaunted twenty-first-century life.

Read More

Still

By Alison Jarvis

Featured Art: The Artist’s Sitting Room in Ritterstrasse by Adolph Menzel, 1851

Somewhere up in the Bronx,

in rented space I’ve never seen, seven

rooms of the old life, waiting

in storage. Shrouded wing chairs,

Persian rugs, your mother’s

engraved silver, nesting and spooning

in a mahogany box. Racks

of your oils. The body of the grand piano

had to be separated from its legs

so everything could fit—

I miss our music.

Sunday, on the little radio

I heard Lotte Lenya sing

that song about searching, her urgency

tilted the room, I was that

off-balance

and dying to hear it again,

even in my own voice. The ether

offers up dozens of versions, none

the one I wanted. One night,

years into your illness—I was whirling—

singing “Pirate Jenny”

when you calmed me—Wait

sweetheart, you said, Lenya

is perfectly still

when she sings that

in the movie.

It’s true. This morning, the light

a slit in the blind, I finally found it

on YouTube. Her body

never moves, only her eyes

and even they stop

near the end. Rapt,

I watched it for hours—

Typed your ghost email,

pressed send.

Read More

A Creature, Stirring

Winner, New Ohio Review Nonfiction Contest

selected by Elena Passarello

By Gail Griffin

Featured Art: The Kitchen by James McNeill Whistler, 1858

It is Christmas night—or, more accurately, two in the morning of December 26th. I am on the small porch at the side of my house. My cat is in my lap. The door to the living room is closed. Every window inside the house is wide open, because the house is full of smoke—a vile, stinky smoke. The porch is winterized, but I have opened one window about six inches because of the smoke escaping from the house. And what I am saying to myself is Well, at least the temperature’s up in the twenties.

The cat is unusually docile. He knows that something fairly strange is going on, and he is cold. I murmur to him that we’ll be all right, over and over. With sudden, crystalline clarity I know that I am absolutely alone in the universe, except for this small animal.

Will it reassure you or just make the whole scene weirder if I tell you that the smoke is from burnt cat food?

Read MoreNovember 1st

By Chanel Brenner

Dia De Los Muertos was Riley’s favorite holiday.

He loved smelling the sugar skulls.

Didn’t mind that he couldn’t eat them.

My husband asks what we should do with Riley’s bicycle.

Who wants a dead kid’s bike?

He puts it in the alley for someone to take.

He rummages through boxes in our garage like we are having a fire sale.

He finds my dead father’s rare coins in a sock, a card from my dead grandmother.

Many believe the dead would be insulted by sadness.

Today, I realized sugar skulls have a space on the forehead for a name.

November 1st is marked as a day to honor lost children.

I open Riley’s closet and look at his clothes.

It is silent, and airless as a church.

My husband runs back out to get Riley’s bike.

Read More

January 12th

By Heather Bowlan

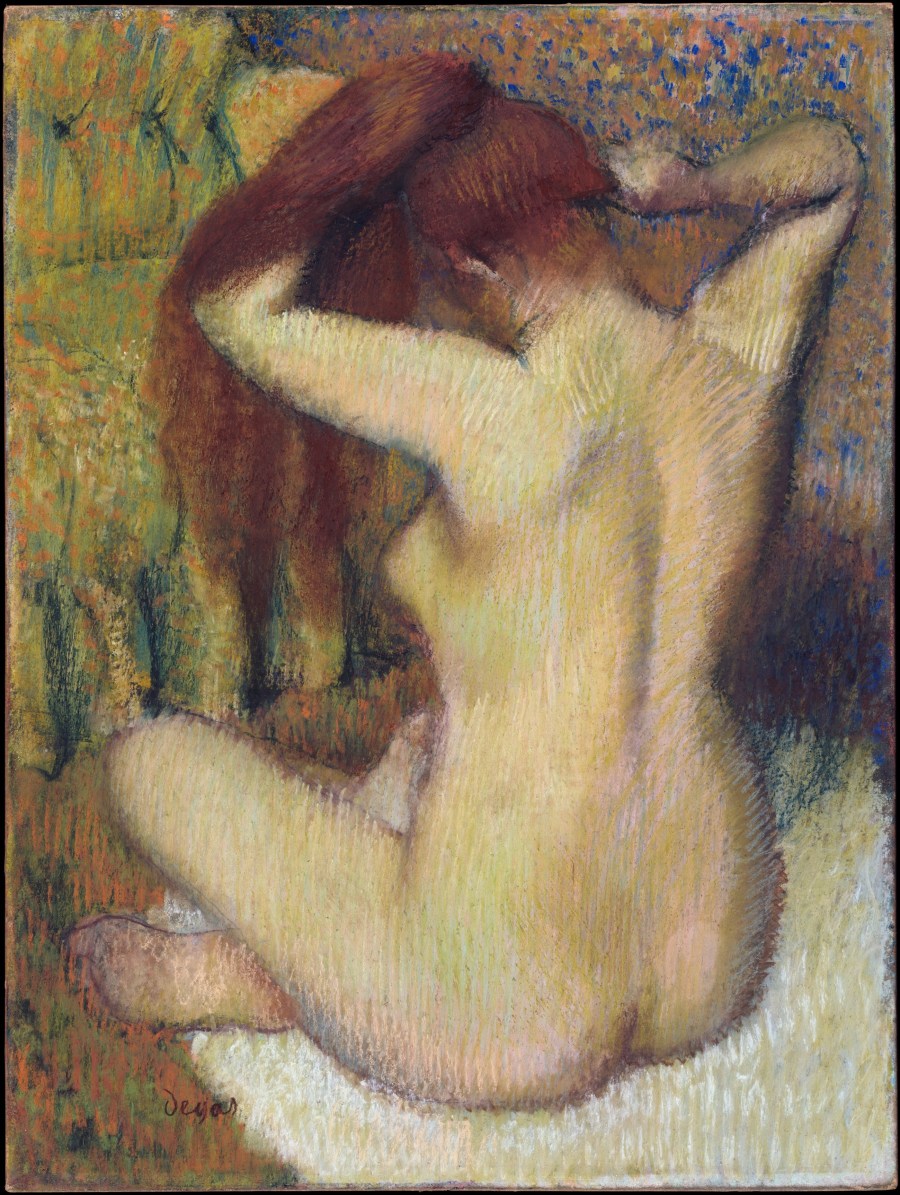

Featured Art: Woman Combing Her Hair by Edgar Degas, 1888-90

the day I told M

I loved her, we were at her new Dom’s

midcentury modern

in Hollywood, the one

with the surprisingly small bedroom.

I always pretend the best version

is what really happened, so I pretended

I didn’t need the wine, didn’t drink

myself to floating while we texted him

photos of our cheery breasts

and matching cherry-bordered

aprons for his birthday, that I wasn’t hungry

for her, that kissing for the camera, lips

open, waiting for him to come

home from work was just a great story for later—

which it is. And she said she would never

love me and I said no chance, really none, never?

and she said no. M always said

L.A. was her town, her true home, and she tiptoed

naked onto the terrace later that night,

a ballerina watching the traffic lights change

on Santa Monica, and I want to pretend

we glided a grand jeté entrance onto

some carcinogenic highway, quick-fast away

from every bare inch of that small room

out into her great city, one I almost knew,

city of spaces, boulevards, exits, of sun

and shifting ground, valleys

and parking lots, an algorithm of streets and

lanes that open out and don’t stop

opening, a mirage city of merges, a city

I nearly loved when its skyline framed the arch

of her neck—even now I see it, I speak it, that sailing

second, it’s the moment I wake up to

every morning I’m in the world.

Read More

Facebook Friends

By Lisa Badner

Fran is my Friend on Facebook.

In the 90s, Fran and I were roommates, then girlfriends.

Dina is my Friend on Facebook too.

I cheated on Fran to be with Dina.

It was in Jerusalem and very dramatic.

Fran can see that I am Friends with Dina on Facebook

because Dina is on my list of Friends.

I Friend Fran’s new girlfriend Ellie,

since we are all pretty friendly.

Ellie Friends Dina. Ellie doesn’t know Dina,

but Ellie Friends all of her Facebook Friends’ Friends.

Ellie is Friends with Alan.

Alan and Ellie were boyfriend and girlfriend in the 80s,

before Ellie was gay.

Alan Friends me. I have never met Alan,

but I was girlfriends with his first wife, Deb,

when Deb was still dabbling.

We weren’t very friendly after that.

Alan and Deb are Friends on Facebook,

though I hear Deb may have recently died.

Fran and Ellie and Dina are also Friends with Deb on Facebook.

Tomorrow I’m going to Friend Deb too.

Read More

Parent/Teacher Conference

By Lisa Badner

Featured Art: Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers by Gustave Caillebotte, 1893

My son’s third grade music teacher

was the girlfriend of my piano teacher

in nineteen eighty-three.

I was a teenager.

She was hip and grown-up with long hair.

She has no clue we ever met.

But I remember her.

I remember hearing her scat sing

while I walked up the stairs.

She also doesn’t know

that I had sex with her thirty-something boyfriend,

rather—that I let him have sex with me—after she’d leave

and after I played the Bach French Suites—

in their Bleecker Street walk-up.

I was desperately trying to be straight

(it didn’t work).

We are sitting on little-kid chairs

and she is discussing my son’s musical prowess,

in spite of his bad behavior in chorus.

She still has long hair, now dyed blonde.

She tells me my son is a little lost,

struggling to find his place.

I know from lost—I want to yell out.

This conference is about my son.

So I nod and smile thinking

about being sprawled out numb

in nineteen eighty-three.

I want to talk about me.

I want to curl up into her arms

and go to sleep.

Read More

This Is Not an Obituary

By Lisa Badner

Featured Art: The Funeral by Edouard Manet, 1867

–For Claudia Card

Claudia, you asked me (in advance) to write your obituary.

You gave me your 37-page single-spaced CV.

Now the time has come,

I have not written an obituary.

After the biopsy results last year

You said I would inherit your music library.

I used to play piano.

I stopped playing piano in 1984.

You nominated me for a graduate fellowship.

You said I would have been a good philosopher.

I got the fellowship. Thank you.

Then I dropped out.

I went back to New York, eventually to law school

to pursue a mediocre career. After your lung surgery

you told your other visitors that I was a judge.

You seemed so proud. Claudia, I kept telling you, administrative judge.

In the 90s I took you on a walking tour

all over Manhattan.

You developed plantar fasciitis

from the hard city pavement.

I took your Ethics class in 1984. You held the chalk like the cigarettes

you used to chain-smoke. Your mother died of lung cancer.

You told me your family was so poor she barely went to the doctor—

the lung tumor protruded from her chest by the time she got someone to look at it.

So in 1989 I lied when you asked me if I smoked.

I still have the coat and blazer I bought

the day I gave you plantar fasciitis.

I don’t have the letters you wrote and the papers you sent me.

The last time I ever saw you,

I hugged you goodbye when my taxi arrived to take me to the airport.

You were in bed, cancer in your brain, maybe your spine.

My heavy backpack fell over me onto your abdomen.

When they moved you to hospice

you said you’d rather I come see you again at this new facility

than come to your funeral.

I didn’t see you at hospice.

I didn’t go to your funeral.

Read More

Response to Medical Questionnaire Furnished by Mount Sinai

By Graham Coppin

I had chicken pox as a child. Rubella and the mumps.

My tonsils came out when I was three. I am not currently

under a physician’s care for any ailment or injury although

see below. I have lived outside the United States because

I was born outside the United States. My left ring toe has

a callus, same spot same toe as my father. He passed away

of bladder cancer and a broken heart. My mother before him

died of stomach cancer and a broken heart. I used to smoke.

Quit years ago and took up other things much worse for me.

I drink when I can’t. I am allergic to penicillin. At least

that’s what my mother told me. One of the many things

I was taught would be my undoing. I am undetectable.

Genvoya keeps it that way. I take Doxepin when I can’t sleep

or need to sleep. I sleep on average seven hours a night.

Today I have high creatinine. Ask me again tomorrow.

Yes, I use a seat belt. My uncle Michael is a schizophrenic

and survives in a state institution. My uncle Mervyn developed

adult onset diabetes and got both legs amputated, leaving me

to carry him up the stairs at my parents’ fiftieth. His wife

my aunt Betty is still going strong spending the money that

there’s no need to bequeath to anyone especially me. She’s barren

my mother used to whisper. I inject testosterone cypionate once

a fortnight into my ass to combat low T. I don’t eat red meat.

I exercise. Pray mostly. My father’s father died of lung

cancer. His wife my grandmother Flo went of dementia,

breathing her last in a pool of her own waste in a home

that used to be a hotel when I was a teen. The hotel where

an older man once lured me to his room and did things.

Read More

The Killing Square

By Michael Credico

Featured Art: Unfinished Study of Sheep by Constant Troyon, 1850

It’s the manipulations that end you. I was told this by Sam Shaw after he learned he’d been promoted to the inside. We were on the outside of the outside in the designated smoking area. I was smoking. Sam Shaw said, “What’s suffering worth?” He broke off the shards of animal blood that had froze to his overalls.

I shook like I was caught in electric wires. The cigarette butt hissed when I let it drop into a snowdrift. I could hardly feel myself living, felt like I was alive as a series of smoke breaks.

Sam Shaw said, “Nothing’s dead-end as it seems.”

“Easy for you to think,” I said. “You’re on the inside now.”

I warmed my hands with the heat of the conveyor’s gear motor, clenched and unclenched until my circulation was good enough that I could reach for my cutter and hand it off to Sam Shaw without either of us losing a precious something. Sam Shaw cut into a plastic clamshell that contained a dress shirt and tie combo. He pulled the tie too tight. I told him he couldn’t breathe. He called himself a real professional. I lined up the next group of animals.

“You ain’t dressed for this no more,” I said.

Sam Shaw looked at me and then the cutter. “Take it easy on me,” he said, taking an animal by its pit, cutting it with no regard for the stainlessness of the shirt.

Read More

Horse on a Plane

By Joyce Peseroff

Featured Art: Horses Running Free from The Caprices by Jacques Callot, 1622

A horse on a plane is a dangerous thing

if the box he’s persuaded to enter shifts

like a boulder or a coffin fragrant with hay

but no exit and midflight he decides no way,

time to bomb this pop stand, burst out

of his lofty corral into a tufted field

asway with timothy, feathers, and prance.

You ask a horse—you don’t tell him—to trot

or whoa, easy there fella, and cross-tie him

with a knot meant to fail if he pulls back.

When the plane bucks, a horse can launch

steel shoes through aluminum, the hiss

of oxygen dropping down the masks.

Then his groom must place a pistol barrel

in the nearest ear and whisper, Easy;

carried on with apples, sugar, and oats,

the gun follows the horse on every flight.

Read More