How Do You Name a Hurricane?

By Amy Lee Scott

Selected as winner of the 2022 Editors’ Prize in Nonfiction by Eric LeMay

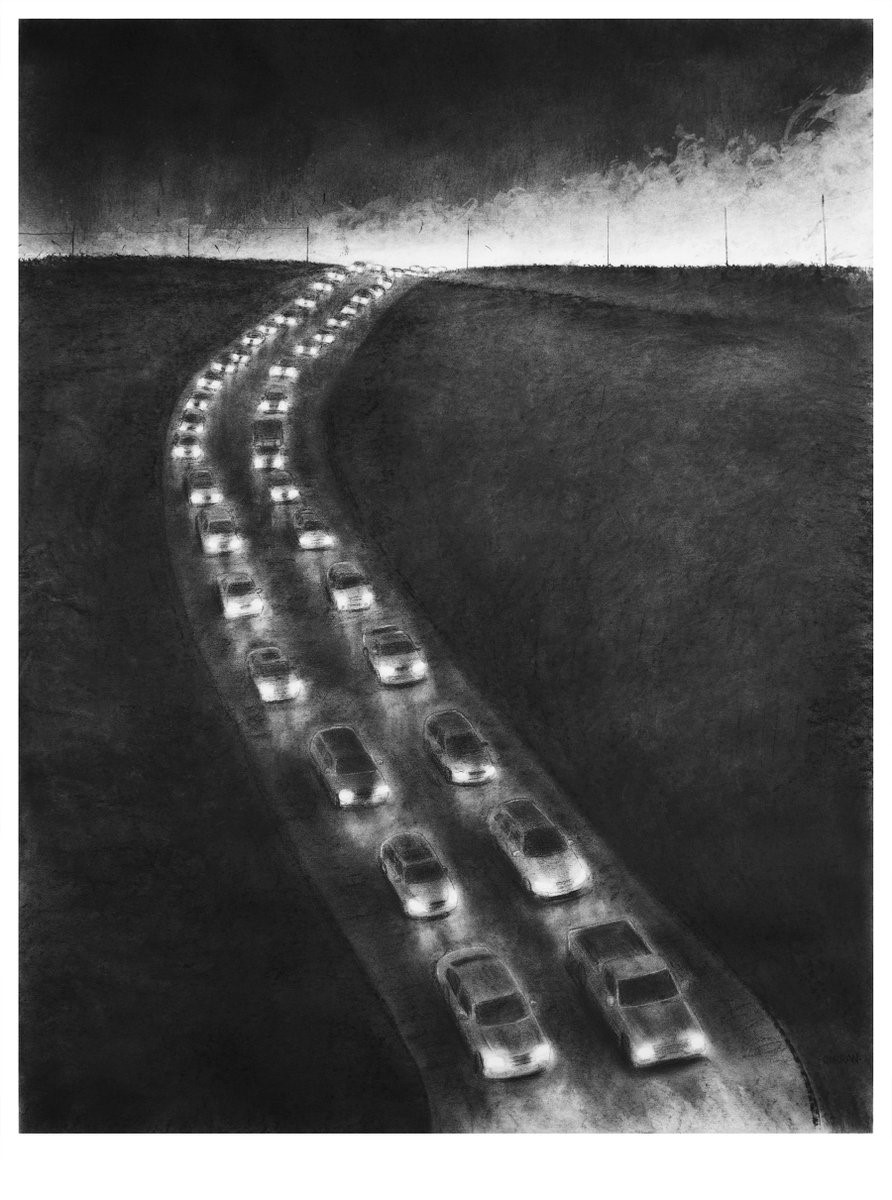

First, watch the storm gathering. On the map there is a bustle of white, so much like a twirling petticoat that spins faster and faster. When it gets big enough, the astronauts post photos. News outlets flash warnings. People clear supermarket shelves, hammer up boards, track down batteries. Outside, the wind thrashes.

* * *

Arthur. Bertha. Cristobal. And Dolly.

Use old names, like our grandparents’. Names that stick. That is why we began to name them: the old labels—just numbers—were not enough. We needed names to contain such catastrophes.

Why would anyone even live there? someone said after looking at photos of decimated islands. They are destroyed year after year.

We weren’t noticing the hurricanes. Here, we were scrolling and scrolling past black squares. Past Black faces:

George. Breonna. Ahmaud. The list went on.

* * *

Read More